South Asians Like Me Get Abortions. Where Are Our Stories?

Inequities in abortion access are only deepening in Asian American and immigrant communities. Our stories matter and deserve to be told.

I found out I was pregnant in my early 20s. I wasn’t ready to become a parent and knew that I needed an abortion. Ironically, as a young public health student working at a local health clinic, I had no idea how I could navigate the health system or where I could safely seek an abortion. I was unfamiliar with abortion funds, had no health insurance, and almost no money. But I was too afraid to ask for help because of the stigma, judgment, and isolation that I feared would follow. Frankly, I also didn’t know who to ask.

When I needed an abortion, I felt trapped, confused, and alone. Today, as it was for me growing up, it is rare to see South Asians represented among those who have abortions. I didn’t see myself or my community represented in any of the stories I read. I didn’t even see them in the pages of research that I studied for school. How was I supposed to get the abortion that I needed?

As the days ticked by, seven weeks pregnant turned into nine weeks, and nine weeks turned into 11 weeks. I grew more and more scared. I can say from firsthand experience that not obtaining an abortion that you want, when you want, is terrifying.

Finally, in secret and on my own, I safely self-managed my abortion with misoprostol from the clinic where I worked. Having an abortion was the best decision for me; yet, for years, I shrouded my story in silence. I didn’t speak of the stigma that I felt or the barriers that I faced when seeking my abortion. But through conversations and in my work as a researcher, I continued to notice the lack of my group and other Asian groups in the data, discussions, and stories on abortion. It was as though the financial and logistical barriers to abortion that were so well-documented for other groups simply did not exist for Asian Americans. I knew this wasn’t true. Inequities in access to care were only deepening in these communities.

As young women, mothers, and elders, many navigated their abortions as I did: silently and on their own. I often wonder if I would have felt so alone in my own story had I known that others, around me and before me, had navigated similar paths.

Asian Americans continue to be erroneously characterized as a group that lacks health challenges in large part because of a public discourse that stereotypes Asians as a “model minority.” This framing implies that Asians are a uniformly successful and healthy monolith. Yet, this myth, rooted in U.S. histories of racism and xenophobia, has long obfuscated the heterogeneity of this population and the obstacles many Asian Americans face when seeking abortion and other health care.

While treated as a monolith in mainstream discourse, Asians are the most diverse racial group in the U.S., comprising over 50 ethnicities from more than 20 countries of origin. Each group has vastly different migration histories, cultures, languages, and health systems that inform their health-care behaviors, access, and outcomes. Nearly 60 percent of the population is foreign-born and many contend with anti-Asian xenophobia and a patchwork of U.S. policies and practices that condition (and limit) health-care access on factors like immigration status, English proficiency, and income. Racial stereotypes, cultural stereotypes, and discrimination also make some Asian groups the target of state-level “sex-selective” abortion bans, which invoke harmful tropes of Asian families’ preference for sons and impose undue scrutiny on their reasons for obtaining abortions. Further, language barriers, cultural stigma, and low rates of health insurance coverage exacerbate access challenges to abortion care for many Asian American groups. This broader context existed well before the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision; Asian American women and people have long known the consequences of abortion restrictions and other barriers to health care.

Now, with abortion in the hands of state legislators across the country, nearly one-third of low-income Asian American women live in states that enacted abortion restrictions after the Dobbs ruling. Combined with existing systemic barriers to care, including cultural stigma and stereotypes, mounting xenophobia, and exclusionary migration policies, the current restrictive environment will only further jeopardize timely abortion care, rights, and justice for many Asian American groups. We should have never ignored or undermined the health and abortion care needs of Asian communities, and we can no longer do so now. The consequences in a post-Roe environment—both persistent and new obstacles that delay or altogether prohibit access to abortion—are more dangerous than ever.

Moving forward in the fight to keep abortion accessible to all, we must commit to centering and making visible the abortion needs and rights of Asian communities. We must ensure that the intersection between immigration policy, health care, and abortion rights is addressed in the pursuit of preserving access for all, including Asian immigrants. Reproductive health research must consistently include and disaggregate Asian populations in the study of abortion. They are not an optional subgroup that can be ignored or tacked on by request. My story and those of others show the harms of ignoring barriers to access that people from communities like mine and many others face. Thoughtful work exploring the needs of Asian Americans and immigrants can bring to bear the range of abortion experiences in these groups, dismantle harmful racial and cultural myths, and shape equitable abortion policies and programs.

We must also work to elevate the stories and collective expertise of Asian Americans, especially those who have had abortions and those most impacted by a post-Roe climate. Many have long paved paths of resistance, fighting to dispel the injurious model minority myth, challenge anti-immigration policies and xenophobia, and destigmatize abortion in their communities and beyond. Centering such efforts helps ensure that the needs, priorities, and experiences of those traditionally isolated and systematically excluded from the abortion discourse inform and anchor any vision for change moving forward, whether that’s advanced by communities, activists, or researchers.

In recent years, as I’ve started sharing my abortion story, I’ve learned the stories of others. Stories shared quietly and across generations. Stories shared in my community, in my family, and even among my ancestors. As young women, mothers, and elders, many navigated their abortions as I did: silently and on their own. I often wonder if I would have felt so alone in my own story had I known that others, around me and before me, had navigated similar paths. These days I share my abortion story, in part, to interrupt the cultural stigma and stereotypes that shaped my experience, but also to dispel the myth that Asian Americans and immigrants don’t have or need abortions. We do. I share my story so that people in my community, my loved ones, the generations that follow, and all others know that we, too, have abortions. We, too, need support as we navigate access barriers and deserve not to feel alone as we do so. Above all, we must see ourselves and be seen in the fight for abortion rights and reproductive justice. Our lives and communities depend on it.

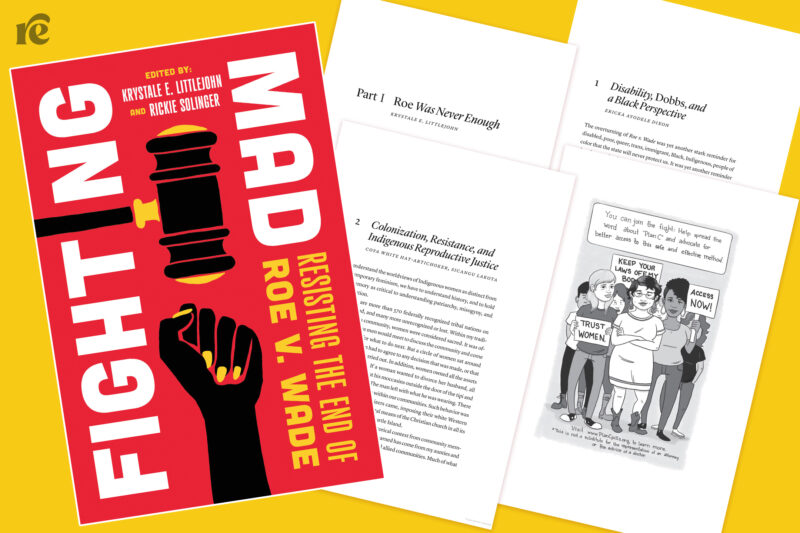

Excerpted from Fighting Mad: Resisting the End of Roe v. Wade edited by Krystale E. Littlejohn and Rickie Solinger, published by University of California Press. © 2024 by Krystale E. Littlejohn and Rickie Solinger.