“Doctor Drain” Threatens Rural Health Care in Iowa

Iowa's legislature and rural communities have yet to address the root causes of the doctor shortage in the state, including incentives for young rural Iowans to take the plunge into medical school.

This month, the Mitchell County Regional Health Center in Osage

became the 14th Iowa hospital in as many years to stop offering

obstetrical services. Families in Osage expecting a child will need to

travel to neighboring cities for final prenatal exams and delivery in

hospitals that offer those services or seek other options.

Births in Iowa’s hospitals have increased by nearly 10 percent in

the past 10 years, but access to obstetrical services has declined in

rural Iowa, as hospitals discontinue labor and delivery services.

It’s a trend that is impacting rural areas not only in Iowa but across the United States.

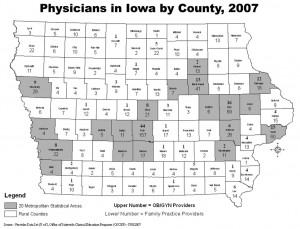

A 2008 report from the Iowa  Red pins represent Iowa hospitals that do not offer obstetrical services. Green pins are Iowa hospitals that continue to offer such services. Click image to access interactive Google map.Department of Public Health notes that

Red pins represent Iowa hospitals that do not offer obstetrical services. Green pins are Iowa hospitals that continue to offer such services. Click image to access interactive Google map.Department of Public Health notes that

of 181 OB/GYN physicians identified in the state, only 46 practice in

rural counties. The vast majority of the physicians are located in

Iowa’s population centers – Polk, Linn, Johnson, Black Hawk, Dubuque

and Scott counties.

The same holds true for family practice physicians. And one county,

Taylor, has neither a family practice physician or an OB/GYN physician

listed.

The reason Mitchell County Regional and other rural hospitals say

they can no longer offer these services is a lack of physicians.

While there is no doubt that rural areas are experiencing physician

shortages, officials say that doctors need more than an invitation and

short-term incentives before they will begin a long-term practice in a

rural setting. While Iowa continues to pursue incentives like loan

forgiveness programs, the legislature and Iowa’s rural communities have

yet to address the root causes of the shortage, including the state’s

dismally low Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement rate and the lack of

encouragement and incentives for young rural Iowans to take the plunge

into medical school.

Physicians Alone Aren’t Enough

"It takes more than a doctor to deliver a baby," said Gloria Vermie,

director of the Iowa Department of Public Health’s Office of Rural

Health. "Sometimes when a hospital or a doctor stops offering

[obstetrical care] it isn’t necessarily any one issue, but a

culmination of issues."

Vermie, who formerly served with the Kansas Department of Health,

said the Sunflower State has made strides in training and retaining

primary care physicians in rural areas with a specialized residency

education program.

“In a mid-sized town called Salina, they have the Smoky Hill Family

Medicine Residency Program,” she said. “It was specifically for

residential, rural-health physicians. A high percent of the doctors who

go through that program end up serving rural areas.”

The philosophy of the Kansas program,

she said, could be summed up as “grow your own,” because a high

percentage of doctors who chose to take part were natives of rural

areas. Following completion of the program, Smoky Hills boasts a 92

percent placement in rural settings.

“It’s a very wise thing for communities to begin doing,” she said.

“They can start to look at their existing students when they are in

junior high to see who might have that potential. They should think:

‘What can we do for these students right now to ensure that they can

get to medical school and then come back home?’”

The “grow your own” approach is something that excites University of

Iowa professor Kelley Donham. He teaches a course in rural health and

agricultural medicine through the university’s College of Public

Health. Donham has also advocated, unsuccessfully, for the school to

begin a full-fledged training track that would focus on rural health

care, priming doctors to work in areas outside major cities.

“It’s quite clear what it takes to get people who want to go into

primary care medicine and into rural areas,” Donham said. “That is, you

get people who are oriented toward primary care who are from

rural areas. Better yet, these individuals need to have spouses that

are from that area. They have to have rural mentors and have a rural

experience. They need to have a sociological connection to that

population.”

Vermie believes that offering loan incentives to medical school

students is key to increasing the number of Iowa’s rural doctors. Such

loans are often forgivable if the student agrees to spend a certain

amount of time practicing in an underserved community. The loans are

important, she said, but they aren’t the solution for retaining doctors

in rural areas.

“Communities may need a higher level of education and training to do

the recruitment and retention,” she said. “We can’t mandate that a

physician stays in [a particular community], but if those local leaders

know all the right strategies to bring those doctors in and assure them

that the community will support them and that certain amenities are

present, then they may have a higher success rate.”

Bobbi Buckner Bentz is director of the Primary Care Office in IDPH’s

Bureau of Health Care Access. One of her duties is to review site

applications for the National Health Service Corps,

a federal program that offers scholarships to medical professionals who

agree to practice in underserved areas. Since 1994, Iowa has offered a

similar program through the Bureau of Health Care Access that is called

PRIMECARRE.

Due to increased marketing and recently approved federal stimulus

funds, the federal program should see significant increases this year.

Bentz has already reviewed 16 and is expecting several more before the

March 27 cut-off date.

Medcaid/Medicare rates key to stopping “doctor drain”

But loan programs aren’t enough to address the many other factors

that challenge doctors who practice in rural areas. In Iowa, the

state’s extremely low Medicaid/Medicare reimbursement rate, the ongoing

nursing shortage, increased liability issues and even limited rural

broadband access all create an environment that can make doctor

retention difficult, observers say.  County-by-county listing of obstetric and primary care physicians in Iowa. Click to view larger graphic.

County-by-county listing of obstetric and primary care physicians in Iowa. Click to view larger graphic.

Christian Fong is vice-chairman of the Generation Iowa Commission,

established by the state to attract and retain young professionals in

the state. He believes that the loan forgiveness program doesn’t offer

enough incentive for medical professionals to give up the pay increases

they can obtain in neighboring states with much higher

Medicaid/Medicare reimbursement rates.

“The loan forgiveness program, which has been the traditional way of

trying to keep [physicians] in rural areas, has been, for the most

part, a failure,” Fong said. “For medicine, sometimes you are dealing

with $250,000 of debt. But what is that much debt when you can make

$50,000 more a year by moving to Minnesota? The economics no longer

works out for loan forgiveness.”

The other piece of the puzzle, according to Fong, is what happens to

a community when the physician meets his or her commitment and moves on.

“If they leave, the community is often left with this huge hole,” he

said. “And it can be very difficult to re-recruit to those rural areas.

So, an OB/GYN that comes into a community begins to assemble a support

system. It’s no longer just a single doctor, but it is all the support

networks that go into having that doctor available. If that OB/GYN

leaves, the hub of that network is gone. What are the other people who

were hired as a part of that support system supposed to do?”

Last year, the Generation Iowa Commission indicated that the solution to Iowa’s “doctor drain” was increasing Medicare/Medicaid reimbursements.

“That’s going to be extremely difficult in this budget environment,”

Fong confessed. “But, until we make a commitment as a state to do it,

we are going to continue to see ‘doctor drain’ out of our state — and

particularly out of rural areas.”

U.S. Rep. Tom Latham, R-Alexander, who has been a significant voice

in the ongoing conversation about Iowa’s nursing shortage, believes at

least some of the burden placed on physicians and hospitals can be

alleviated with technological advances. Latham secured $95,000 in

funding for the Newborn Monitoring Initiative, a first-of-its-kind

telemedicine technology that has been spearheaded by Gunderson Lutheran

Health System and Gunderson Clinic in Decorah.

The system allows physicians to send real-time data from rural

clinics to medical center specialists. The data can help facilitate

consultations, improve coordination of care and give women and babies

in rural regions access to specialists that might otherwise not be

available without extended travel. Such advances can also help a family

practitioner in a rural setting from feeling isolated and overburdened.

Vermie, meanwhile, says that economic development strategies

currently employed by communities for potential business recruitment

and retention could be modified to apply to medical professionals.

“There needs to be a local discussion on how the communities can

appeal to these medical professionals — especially the young ones,” she

said. “How do you entice them? How do you appeal to them? How do we

cultivate the support services that will ensure this doctor will have a

good practice without being overburdened?”