Purity Culture as Rape Culture: Why the Theological Is Political

By failing to equip women to understand their own agency and bodily autonomy, the evangelical purity movement creates an environment that is ripe for rape.

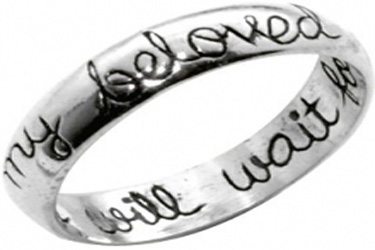

When I was 14 years old, I stood in front of my 800-member Baptist congregation with my parents as they handed me a small diamond ring we’d bought together at Walmart. Before the church body and before God, I pledged that no man shall touch my special places until after we had said “I do.” I pledged to keep pure.

Thirteen years later, I still wear the ring on my right hand, but now it is simply out of habit. It doesn’t mean anything to me anymore besides being the nicest piece of jewelry I own. I grew up in evangelical purity culture, and like many of my fellow millennial Christians, I’ve left it behind.

In evangelical America, a woman’s potential relationships and sexual choices are of paramount importance. Relationship guides and purity pledges are a cottage industry in evangelicalism, but the influence reaches far beyond just evangelicals. During the recent government shutdown and the ongoing battle over the Affordable Care Act, we’re seeing the far-reaching effects of a theology in which a woman’s purity is the most important part of her life.

Purity culture kicked off in response to two events in the mid-20th century: the sexual revolution that characterized much of second-wave feminism, and the 1973 ruling of Roe v. Wade. The return to conservatism in the 1980s saw the beginnings of a resurgence of interest in womanly purity and “biblical” gender roles. With the set roles of the 1950s forever upended, many conservative evangelicals scrambled for a foothold—and they found it in the concept of purity pledges and balls.

The first purity ball was held in 1998 in Colorado. Today, such balls are a staple of a conservative evangelical girl’s life. Fathers and daughters dress up in their nicest outfits, and the daughters make a pledge of purity to their father and to God. In the most extreme examples, the daughter is considered under the authority of her father until the day she marries, at which point she transfers that authority to her husband.

If she remains invested in the purity movement throughout her teen years—which would mean regularly attending a typical evangelical youth service—she will be exposed to an abundance of narratives about how keeping oneself pure is a fight that must be won, that it is what God wants, and, most importantly, that her body does not belong to her, but rather to her future husband, and a lapse in purity is a betrayal of her future relationship.

That last part is an extremely important one, and one that many secular students of evangelical purity culture miss—it’s the backbone to the entire concept of purity, the theological underpinning that makes conservative evangelicals such a unique breed. Until we understand just how deeply this “You are not your own” theology is intertwined within purity culture, we will not be able to truly understand the politicians who discuss rape in horrific terms, or the reasons Christian employers see fit to interfere with their employees’ access to birth control.

Purity culture, in the evangelical world, is nothing more than an elaborate form of rape culture. But it is rape culture embedded so deeply that rooting it out requires challenging the very forms of Christology upon which many evangelicals have built their beliefs. In other words, making the change to believe in bodily autonomy and unassailable agency of the individual means changing how one views all aspects of faith. This conflict, naturally, is why traditional feminism and Christian evangelicalism are often so at odds. The challenge of bodily autonomy is, for many conservative evangelicals, anathema to their very belief structure.

To understand purity culture as rape culture, we must understand why bodily autonomy is such an issue. For the evangelical, “dying to self”—or sacrificing one’s selfishness for the greater good of the Gospel—is one of the highest honors one can have. This is often interpreted as subsuming one’s desires, one’s individuality, into the will of God. Cobbling together ideas like “God’s ways are higher than our ways,” and the Apostle Paul’s assertion that what looks like foolishness to the world is wisdom for the Christian, evangelicals lay claim to life in an “upside-down kingdom,” where being last means they’re really first.

In response to what is seen as a sex-saturated world in which women are asserting their sexual agency and exploring their sexual identities through their experiences, evangelical purity theology seeks to remind people that self-sacrifice—giving up one’s selfhood—is a Christian duty. Unfortunately, they take this so far as to believe that a wife’s body is not her own, that a woman cannot say no to her husband, and that it is sin to withhold sexual gratification from one’s partner.

You can see where this comes into conflict with a feminism that preaches enthusiastic and continued consent.

Purity culture and rape culture are two sides of the same coin. Prior to marriage, women are instructed that they must say no to sex at every turn, and if they do not they are responsible for the consequences. This method of approach—“always no”—creates situations in which women are not equipped to fully understand what consent looks like or what a healthy sexual encounter is. When the only tool you’re given is a “no,” shame over rape or assault becomes compounded—because you don’t necessarily understand or grasp that “giving in” to coercion or “not saying no” isn’t a “yes.”

In Dateable, a Christian dating guide, authors Justin Lookadoo and Hayley DiMarco reinforce the idea of women as sexual gatekeepers. Throughout the book, we read that “guys will lie to you to get what they want,” and that all guys ever want is to have sex. So it is up to the girl—as discussed in faux-feminist “girl power” terms—to say no. Which is all well and good, until you realize that, in the authors’ estimation, a girl has the power to say no up until the moment she sends the wrong signals, because men are animals who can’t control themselves. Yes, the guide literally says that:

Don’t tease the animals. Have I mentioned that guys are visual? They get turned on by what they see. … So listen: please, PLEASE don’t tease us. To show us your hot little body and then tell us we can’t touch is being a tease. You can’t look that sexy and then tell us to be on our best behavior. Check yourself – if you’re advertising sex, you’re going to get propositions. … A guy will have a tendency to treat you like you are dressed. If you are dressed like a flesh buffet, don’t be surprised when he treats you like a piece of meat.

I was raised with the idea that I didn’t have a right to my own body, and that I didn’t have the right to say yes until I was married, at which point I didn’t have the right to say no. My body was never my own, but rather the property of whatever man happened to ask me to marry him. My virginity was the most precious thing I had to offer, and it was my responsibility to protect it, and if I was coerced into “giving it away,” I would have to repent.

The purity movement not only robs women of their agency by not allowing them to say yes, it robs them of the ability to understand what it means when a “no” is not respected. By failing to equip women to understand their own agency and bodily autonomy, the evangelical purity movement creates an environment that is ripe for rape.

Sarah Moon, a blogger at the Patheos spirituality channel, has written extensively about the acceptance and promotion of rape within conservative evangelical relationship guides. She studied four different Christian dating guides, examining their treatment of consent and rape while promoting purity. She published her findings on her blog (which are being turned into an article for the Journal of Integrated Social Sciences this spring). She writes that Christian dating guides often claim to be against rape while promoting concepts and ideas that contradict this stance (emphasis hers):

the lack of consent in these books isn’t outrightly stated [sic]. It’s subtle and mixed in with language that gives the illusion that a full range of options is available to people. The book Real Marriage shocked me by including (what? no way!) some relatively healthy discussion of the issue of marital rape. The Driscolls condemn marital rape strongly (pg. 202), state that any intercourse forced on someone without consent is rape (pg. 121), and tell husbands that they should never coerce their wives into having sex (pg. 163).

There’s a catch, though.

Husbands, maybe you can’t coerce your wives into sex, but Mark Driscoll, Cage Fighting Jesus, and the Bible sure can! Women can say no to marital sex, sure. You can. But according to Real Marriage, that doesn’t mean you should or that it’s really okay for you to do so.”

A woman asserting her right to say no after the bonds of marriage have been fixed is viewed as an affront to a solid marriage. Within the evangelical church, women who assert any bodily autonomy outside what is ascribed to them by gendered theological roles are to be avoided. If they say yes before marriage, they are tempting Jezebels, luring men off the path of glory; if they saying no after marriage, they are frigid, selfish wives who will be at fault if their husband strays.

This is what many of our elected Republican officials believe. This is why we get statements about “honest rape,” or arguments that women who use birth control are sluts. This is the motivation behind several Protestant Christian colleges and Catholic hospitals suing the government in order not to provide birth control to their employees. This is why, when a rape exception to abortion bans is proposed, Christian politicians are quick to imply that women may “cry rape” to get abortion access.

Fundamentally, evangelical, right-wing politicians do not believe women have a right to their own bodies, whether that control be related to purity or rape or birth control or abortion. This is beyond simply a political issue—it is, at heart, theological. And this fight is far from over.