Dr. King and the White Progressive™

The parallels between the white moderates whom Dr. Martin Luther King criticized in 1963 and certain white progressives whom many Black activists are criticizing in 2015 couldn't be clearer.

In the wake of the white progressive think pieces decrying the Black Lives Matter activists as rude, stupid, immature, idiots, bullies, participating in a circular firing squad, or alienating allies—as well as similar sentiments expressed on Facebook, Twitter, and in the comments of my previous articles (here and here)—the parallels between the white moderates whom Dr. Martin Luther King criticized in 1963 and certain white progressives whom many Black activists are criticizing in 2015 are clear.

A little background will elucidate the point.

In the spring of 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King along with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) began to organize a series of nonviolent protests in Birmingham, Alabama. These protests consisted of demonstrations and sit-ins that targeted white-owned businesses and white churches. On April 10, the City of Birmingham issued an order enjoining the protests. King and the protesters ignored the injunction in an act of direct civil disobedience. On April 12, King and 50 protesters were arrested and jailed.

On April 13, a group of white clergymen penned an open letter, titled, “A Call for Unity,” which called for cooler heads to prevail. They criticized the confrontational nature of the protests and called for King and the protesters to obey the injunction and pursue justice through lawful means:

We the undersigned clergymen are among those who, in January, issued “An Appeal for Law and Order and Common Sense,” in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. We expressed understanding that honest convictions in racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts, but urged that decisions of those courts should in the meantime be peacefully obeyed.

The clergymen also criticized the demonstrations as “unwise and untimely” and being led by “outsiders”:

However, we are now confronted by a series of demonstrations by some of our Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders. We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized. But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.

After pointing out that some of the Black leadership disagreed with King’s tactics—“[w]e agree rather with certain local Negro leadership which has called for honest and open negotiation of racial issues in our area”—these white clergymen went on to claim that the nonviolent protests were inciting “hatred and violence”:

Just as we formerly pointed out that “hatred and violence have no sanction in our religious and political traditions,” we also point out that such actions as incite to hatred and violence, however technically peaceful those actions may be, have not contributed to the resolution of our local problems. We do not believe that these days of new hope are days when extreme measures are justified in Birmingham.

The clergymen concluded by calling for “law and order and common sense”:

When rights are consistently denied, a cause should be pressed in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets. We appeal to both our white and Negro citizenry to observe the principles of law and order and common sense.

In response, King penned his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” in which he noted that freedom must be demanded by the oppressed and that there’s no such thing as a “well-timed” direction action in the eyes of the oppressed:

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was “well timed” in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

King also criticized the white moderate, noting that they seemed more devoted to order than to justice:

I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

King also pointed out that it was not the protesters engaged in nonviolent direct action who were the cause of racial tension, but rather that the protesters were merely bringing that tension to light:

I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress. I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that the present tension in the South is a necessary phase of the transition from an obnoxious negative peace, in which the Negro passively accepted his unjust plight, to a substantive and positive peace, in which all men will respect the dignity and worth of human personality. Actually, we who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with. Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened with all its ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.

King noted that perhaps he had been too optimistic in thinking that the white moderate would see the need for “strong, persistent, and determined action”:

I had hoped that the white moderate would see this need. Perhaps I was too optimistic; perhaps I expected too much. I suppose I should have realized that few members of the oppressor race can understand the deep groans and passionate yearnings of the oppressed race, and still fewer have the vision to see that injustice must be rooted out by strong, persistent and determined action.

He also praised those white allies—”few in quantity,” but “big in quality”—who were in the trenches with him and committed to social revolution:

I am thankful, however, that some of our white brothers in the South have grasped the meaning of this social revolution and committed themselves to it. They are still all too few in quantity, but they are big in quality. Some—such as Ralph McGill, Lillian Smith, Harry Golden, James McBride Dabbs, Ann Braden and Sarah Patton Boyle—have written about our struggle in eloquent and prophetic terms. Others have marched with us down nameless streets of the South. They have languished in filthy, roach infested jails, suffering the abuse and brutality of policemen who view them as “dirty nigger-lovers.” Unlike so many of their moderate brothers and sisters, they have recognized the urgency of the moment and sensed the need for powerful “action” antidotes to combat the disease of segregation.

A comparison of King’s criticisms of the white moderate to many Black Lives Matter activists’ criticism of the white progressive™ further illustrates the similarities between the two.

First, the eight white clergymen who called for “unity” called King and his protesters “outsiders.” Some of the more vocal critics of Black Lives Matter are doing the same with Black Lives Matter activists.

Many white progressives, for example, have been calling the two young women who disrupted a Bernie Sanders rally over the weekend, Marissa Johnson and Mara Willaford, “outside agitators,” pointing to the fact that Marissa Johnson belongs to a group called Outside Agitators 206. Some have claimed the women are engaged in some Clinton or Soros-funded astroturf campaign. (A quick review of OA 206’s website reveals nothing nefarious, and yet the conspiracy theories are flying fast and furious. And the “Soros as Boogey Man” tactic is straight out of the right-wing playbook; that white progressives are using it against Black people is mind-boggling.) In addition, many have also refused to recognize that Johnson and Willaford are affiliated with Black Lives Matter, despite confirmation from the movement’s founders.

Second, as with the white clergymen who criticized King’s protests as “untimely and unwise,” so too have many white progressives criticized Black Lives Matter protests in similar terms. The sentiment seems to be: “We’re in an election season. Black people should just chill out or else they’re going to hurt Sanders’ chance of election. Now is not the time.”

Third, just as the white clergymen called for the protesters to negotiate with city leaders rather than take to the streets, so have many white Sanders supporters wondered why Black Lives Matter activists are protesting his rallies and events rather than asking Sanders politely for a rap session behind closed doors.

Fourth, just as the white clergymen pointed to other Black leaders who disagreed with King’s tactics—“[w]e agree rather with certain local Negro leadership which has called for honest and open negotiation of racial issues in our area”—in order to bolster support for their own criticism, so too have many white progressives glommed on to the criticisms of Black people who disagree with Black Lives Matter activists’ tactics to promote their own criticism. (To be clear, Black people are not a monolith and every movement for Black liberation has included intra-community conflict. Malcolm versus Martin, anyone?)

The similarities between the white moderate of the 1960s and the white progressive™ of 2015 are remarkable.

And yet many white progressives who are behaving more like the white clergymen who opposed King than the white allies who supported King are the first to criticize the Black Lives Matter activists for not being more like King. They are demanding that Black people follow King’s teachings.

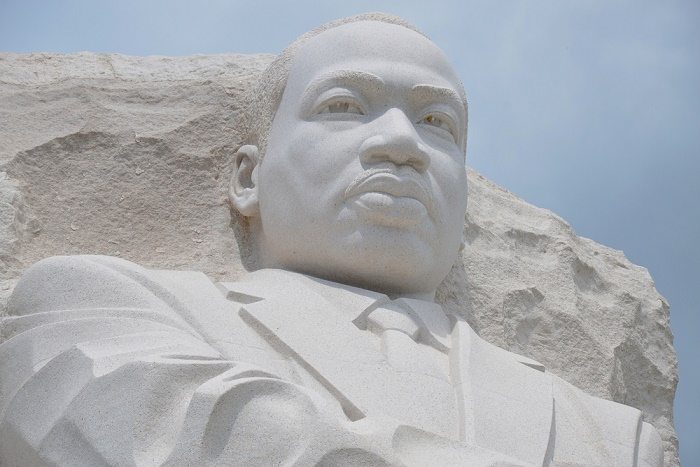

But the King far too many white folks are holding out as an exemplar for current civil rights activists is not the real King. It’s the whitewashed hagiographic version of King. It ignores that King was a disruptor. It ignores that King was a lawbreaker. It ignores that King was not beholden to protesting the right thing, at the right time, in the right space according to white moderates’ timetable.

King recognized—as the Black Lives Matter activists do—that the right time to protest oppression is right now. Oppression must be rooted out wherever it lies.

Those who have responded to my articles by pronouncing that Black Lives Matter has lost an ally (as if that’s some sort of threat), or that I’m racist for expressing my profound disappointment with certain white progressives, are the precise sort of white folks who, unlike true white allies, refuse to recognize the urgency of the moment. They are more concerned with tone and respectability politics than they are about the state of emergency in the Black community.

And sadly, as evidenced by some of the comments, tweets, and hate mail that I have received, they are more concerned with Black votes than Black lives.

“We support Black Lives Matter, but I don’t support the tactics of these activists.”

“Black Lives Matter is dividing the progressive movement.”

“You’re hurting the chance of electing the only person who cares about you.”

“Bernie was fighting for you before you were born.”

Such sentiments are similar to the claims of the white clergymen who asked Dr. King and the protesters to “observe the principles of law and order and common sense.” These are not the claims of allies. These are the claims of oppressors or, at a minimum, of people so comfortable with white supremacy and the privileges it grants, that they aren’t truly willing to dismantle it.

White progressives™, too many of you are calling for unity but really what you are demanding is that Black people stop protesting the rampant state violence in our community until the right candidate is elected. You want Black Lives Matter to stop protesting until 2016.

Well, that’s not going to happen.

There can be no unity when certain people declare that they no longer support Black Lives Matter because they disagree with the movement’s tactics. There can be no unity when the first response to Black people expressing their frustration with the racist rhetoric of certain white progressives is to presume that activists are expressing frustration with you specifically and to proclaim, “I’m not racist.”

Ultimately, there can be no unity when you demonstrate that you care more about order than justice. That you care more about getting a particular candidate elected than ending the scourge of state violence against Black people.

White progressives™ cannot threaten Black people into voting for a particular candidate. Not this time. The crisis in our community is too great and we are well aware of the political power that we now possess.

But what you can do is demonstrate that you are against the state-sanctioned killing of Black people no matter what and that you support Black Lives Matter unconditionally.

And if you can’t do that, that’s fine, but know this: We will not stop protesting. We will just protest without you.

Author’s note: The bold emphasis is mine.