By the Way, Fetuses Can’t Consent to Health Care

In case any Fifth Circuit judge was confused.

When it comes to a pregnant patient suffering a medical emergency, who do we trust to make a difficult call in a difficult situation? The patient and the doctor treating them? State legislators with no medical training?

Or maybe the fetus itself should have a say. “Sure, I’m killing you, but I think I’m the one who should get to live.”

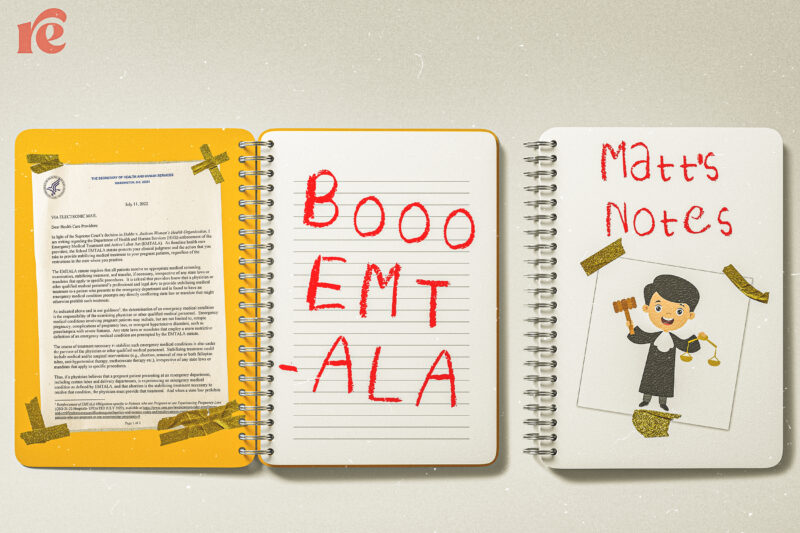

You may think I sound ridiculous, but this seems to be the reasoning behind the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling in Texas v. Becerra, Texas’ cooked-up challenge to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA).

EMTALA is a federal statute that requires Medicare-funded hospitals to provide stabilizing treatment to any patient who shows up in the emergency room, regardless of their ability to pay. The Biden administration appeared to be ready to use EMTALA as a lifeline for people in abortion-hostile states who find themselves needing life-saving abortions in hospitals where doctors are reluctant to provide such care out of a very real fear of breaking the law.

Soon after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the Biden administration issued guidance clarifying that EMTALA’s requirement that Medicare-funded hospitals provide stabilizing treatment included a requirement to provide abortion care if necessary.

This wasn’t a policy shift. Nor was it an effort to turn poor “pro-life” doctors into servants of Big Abortion.

Fetuses can neither physically nor philosophically make a choice about what kind of health care will be provided to the person carrying them. And to argue otherwise is to assign a level of “personhood” to a fetus that the Supreme Court has not been willing to assign (yet).

It was simply a polite tap on the shoulder from the federal government to abortion-hostile states like Texas that believe their total abortion bans should trump the federal requirement to provide life-saving abortion care, not just when a patient is on death’s door, but also when a patient’s health is in serious jeopardy. It was just a heads up, as if to say, “Hey, abortion is health care, and if it’s required to stabilize a patient, then you have to do it.”

Texas, of course, became immediately hysterical and filed a lawsuit against the Department of Health and Human Services, even though it’s not customary to file a lawsuit in response to a document that simply explains a state’s obligations under federal law. But this is Texas, and if there’s one thing Texas is going to do, it’s going to be first out of the gate to stick it to pregnant people seeking abortions. And even though this particular lawsuit is nonsense, I’ll concede that Texas and its attorneys at conservative Christian law firm (and Southern Poverty Law Center-designated hate group) Alliance Defending Freedom would have eventually found their way into Judge Matt Kacsmaryk’s friendly courtroom in Amarillo, Texas.

When a case ends up in Amarillo, you can be sure that it’s either a cooked-up challenge or is short on legal reasoning and long on religious vibes. You can also be sure that whatever conservative filed the lawsuit is looking for Kacsmaryk to work his magic—to invent principles of law that don’t exist, grossly misread principles of law that do exist, and to rewrite statutes to suit the Christofascist agenda that seems to be driving conservative policy these days.

And that’s what happened in Texas v. Becerra, where Kacsmaryk—and the Fifth Circuit— agreed that, essentially, there’s no such thing as a life-saving abortion since the abortion terminates the “unborn child” and EMTALA requires doctors to provide stabilizing treatment to that unborn child.

You may be thinking to yourself, “that sort of makes sense.” You probably are quibbling with the use of the term “unborn child” since it’s not a scientific word, and the fact that it appears in EMTALA probably frustrates you as much as it does me. But just looking at the statute as written, how can stabilizing treatment include abortion? That’s not going to stabilize the unborn child.

Well, yes—that is true. But the Fifth Circuit literally rewrote the statute to make that true.

The statute doesn’t require that life-saving care be provided to the pregnant person and their unborn child. The statute specifically says that emergency care must be provided if the pregnant person has a medical condition that will place their life or the life of their unborn child in serious jeopardy.

“Or.”

Not “and.”

It’s the patient who gets to decide what treatment they want. Fetuses can’t consent to health care. A fetus also can’t refuse health care chosen by the person carrying it. Moreover, EMTALA neither contemplates nor requires emergency room doctors to consider the wants and needs of a fetus when presenting a pregnant patient with stabilizing treatment options. How could a doctor consider those wants and needs if the fetus is not able to communicate them?

And to the extent that the state—or anyone—would presume to speak for the fetus, how do we even know that the fetus would want to be born?

The very idea is nonsensical. But have you seen some of the decisions the Fifth Circuit has been squeezing out lately? They’re a “clown car of reactionary ideologues,” as Lisa Needham so eloquently put it in Balls and Strikes. They’re terrible collectively and individually: Judge James Ho recently lamented that people suffer an “aesthetic injury” when pregnancies are terminated. To bolster that claim, he cited cases involving people being deprived of the aesthetic pleasure of viewing animals and plants by action that threatens that animal or plant life.

And Edith Jones has been relegated to the least-bad of the judges on the Fifth Circuit, but this is a woman who once claimed that driving 150 miles to an abortion clinic was no big deal if the roads are flat and “uncongested.” So let’s not forget how terrible she is, even though she’s been out-terribled by the Trump judges flanking her.

So of course, the Fifth Circuit eagerly signed on to the idea that when Congress enacted EMTALA, what it really was doing was enacting legislation meant to provide life-saving health care to a fetus.

EMTALA’s requirements are simple and they make sense. The statute was passed to deal with the scourge of patient dumping: Hospitals would throw indigent patients out onto the street or dump them in the parking lot of another hospital to avoid spending money they might not recoup caring for the patient. EMTALA nixed that practice.

Quite simply, if a poor patient shows up in a Medicare-funded emergency room, that emergency room has to perform a medical examination. If that patient has an emergency medical condition, the emergency room doctors have to provide stabilizing treatment to the patient.

The statute even defines “emergency medical condition” to be a medical condition of sufficient severity that the absence of immediate medical attention could result in placing the health of the pregnant person or their unborn child in serious jeopardy.

I added the emphasis on “or their unborn child” for a reason—the statute contemplates that a pregnant person faced with an emergency that requires a life-saving abortion will make a decision for themselves as to whether to proceed with the abortion.

The Fifth Circuit, however, rewrote the statute to require stabilizing treatment of the pregnant person and their unborn child—not or their unborn child—and there’s a reason for that: An abortion terminates a pregnancy, and how can an abortion ever qualify as stabilizing treatment for the unborn child if, in anti-choice terms, the abortion “kills” that child?

That’s what the Fifth Circuit interpreted EMTALA to do: require doctors to take into account the unborn child’s unspoken wishes presumably to live.

But that’s asinine. Fetuses can neither physically nor philosophically make a choice about what kind of health care will be provided to the person carrying them. And to argue otherwise is to assign a level of “personhood” to a fetus that the Supreme Court has not been willing to assign (yet).

When it comes to a pregnant patient suffering a medical emergency, an emergency room doctor at a Medicare-funded hospital is required to provide stabilizing treatment to a pregnant person even if the pregnant person themselves is not in serious jeopardy but the fetus is. That’s why the statute requires stabilizing treatment for the “pregnant person or their ‘unborn child,’” not “and their ‘unborn child.’” In other words, the emergency room wouldn’t be able to deny life-saving health care to a pregnant person if the fetus was somehow experiencing a medical emergency while the pregnant person was not. (I can’t think of a medical situation that would fit the scenario I laid out. I’m not a doctor. I’m sure I’ve seen it on Grey’s Anatomy, though, so I feel pretty qualified.)

But that’s not how the law works anymore. EMTALA has been rewritten. In Texas (and Louisiana and Mississippi, which both sit in the Fifth Circuit), if an abortion will save the pregnant person’s life, that’s too bad. Because the fetus probably wouldn’t want an abortion—if it could talk, that is.