What Ever Happened to All the Abortion Boats?

There were many grand ideas about how to connect people to abortion care after the fall of Roe v. Wade. Not all of them panned out.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a floating abortion clinic sailed in to save the day, providing care in federal waters.

At least, that’s what one man wanted people to believe.

Unfortunately, his hamfisted and awkwardly named operation, Abort Offshore, was most likely a hoax that never produced anything even resembling a floating clinic. But this was not the only pie-in-the-sky plan to innovate abortion care post-Dobbs.

In the first few months after the overturn of Roe v. Wade in 2022, unusual ideas to help people access in-person abortion care captured outsized media attention, thanks, perhaps, to the opportunity they provided for an uplifting spin on a deluge of tragic news. But these ideas ranged from ambitious to completely outlandish, and many never got off the ground.

More than two years later, are people really accessing abortion by boat, mobile clinic, or private plane? Rewire News Group revisits the bold abortion care ideas that worked out—and the ones that fell apart.

The (probably) fake boat

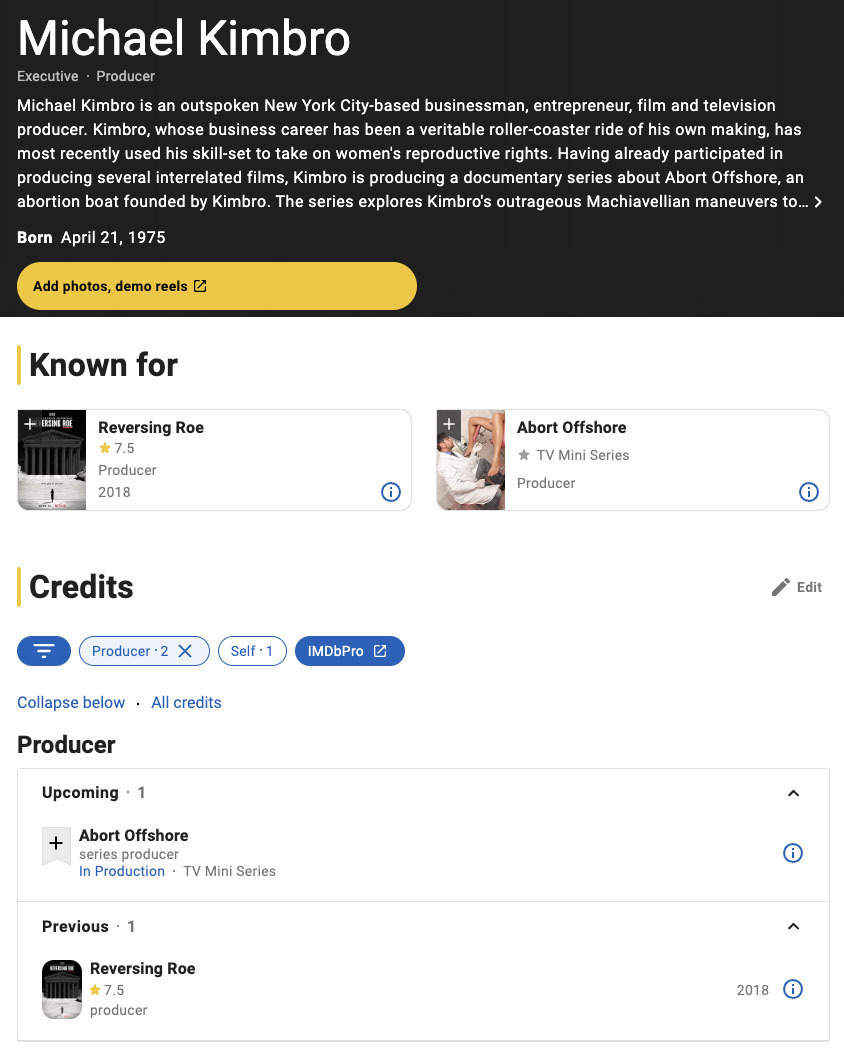

In one of the most bizarre stories from the immediate Dobbs aftermath, a man named Michael Kimbro launched an organization called Abort Offshore and claimed—only about a month after the Dobbs decision—that he had already provided 34 procedural abortions on a boat in the Gulf of Mexico. Less than a month later, he said that number had grown to more than 100, and at other times put the figure at 188 or 242.

Kimbro has no medical background, and even acknowledged in an interview with Austin news station KXAN that he “should not be running any medical facility.” According to Texas licensing records, Kimbro’s wife is a registered nurse, but her level of involvement with the scheme is unclear.

In an interview with Jezebel, Kimbro claimed to have two licensed doctors working for him. But when the Louisiana Illuminator asked for the doctors’ names to verify their licenses, Kimbro declined. He did connect Jezebel with two women who claimed to have been Abort Offshore patients, but their identities couldn’t be verified either. His answers about the clinic’s emergency protocols also left much to be desired.

If all that weren’t suspicious enough, it appears the venture may have been an attempt to sell some kind of docuseries. Kimbro’s IMDb page credits him as the series producer of Abort Offshore, described as “a story about a mysterious abortion boat in federal waters off the coast of Texas within weeks of overturning Roe v. Wade. The series explores its owner’s outrageous Machiavellian maneuvers to restore women’s reproductive rights.”

The IMDb page also lists him as a producer on the documentary film Reversing Roe. However, Kimbro’s name does not appear in the credits, and the film’s actual producers confirmed to RNG that he had no involvement in the project. An archived version of the page from 2022 shows Kimbro was also previously listed as a producer on The Janes, another abortion-related documentary. His name doesn’t appear in the credits of that film, either.

This apparent grift would seem to fit in with Kimbro’s past, which includes a string of arrests and civil lawsuits related to fraud. At least two Facebook pages are run by people who say they were scammed by Kimbro’s previous business ventures, a string of furniture companies.

Per the Internet Archive, the Abort Offshore website disappeared sometime in 2023. It briefly redirected to the Texas Right to Life website and now simply doesn’t load.

Kimbro is one of several people who activist anti-abortion attorney Jonathan Mitchell has sought—unsuccessfully—to depose in order to determine whether they violated S.B. 8, the bounty hunter-style six-week abortion ban. Kimbro’s antics also inspired Texas Rep. Randy Weber to introduce the Ban Offshore Abortion Tourism Act in 2023, but the bill was never acted upon in committee.

RNG was not able to contact Kimbro for comment.

The (potentially) real boat

Casting even more doubt on the idea that Kimbro ever had a functional floating clinic is the work of Dr. Meg Autry, an OB-GYN and professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

As an actual abortion provider and medical educator, Autry knows what’s required to safely run a clinic. And she began working on the idea of a floating clinic long before the 2022 Dobbs decision. Autry’s planning goes back at least as far as 2019, she said, and her organization, PRROWESS, became a 501(

Autry began consulting with maritime experts and lawyers to figure out how to provide abortion procedures up to 16 weeks on a boat in the Gulf of Mexico. Her proposed clinic would also provide contraception, STI testing, and potentially even vaccinations.

Planning accelerated following the Dobbs leak, and once the decision was finalized, “we had unprecedented attention both from the media and from foundations,” Autry said.

But there was a problem: “We are just too high-risk for foundations,” Autry said. PRROWESS’ projected cost to buy and retrofit an appropriate vessel is $10 million. And foundations weren’t willing to invest so much in a novel plan that might not work out. However, they were willing to fund operating costs. In other words: Get your boat, and then we’ll get you the money.

So to become a reality, PRROWESS would need a very wealthy person (or people) willing to fund a risky project.

According to Autry, capital is the only obstacle. Given the money, PRROWESS could be ready to launch in six months.

Autry is also waiting to see what happens in the November election to decide whether or not it makes sense to keep pressing forward. If at any point her organization folds, she plans to donate all funds raised—just under $300,000 so far—to abortion funds in the Gulf states.

Abortion on the road

Only months after the Dobbs decision, I reported for Cosmopolitan on Abortion Delivered, an initiative from Just the Pill to bring mobile clinics to Colorado.

As the name suggests, Just the Pill got its start as a provider of medication abortion only. When FDA regulations still required in-person dispensing of mifepristone, Just the Pill distributed the medication via vans that drove around its home state of Minnesota.

With Dobbs on the horizon, Just the Pill began planning a fleet of mobile clinics that could provide both pills and procedures. The idea was that the clinics would stay in legal states, but would be able to drive right up to the borders of ban states, shortening the distance patients needed to travel.

When I profiled the organization in 2022, Just the Pill already had a mobile clinic dispensing abortion pills on the ground in Colorado. A second van outfitted to provide first trimester procedures was preparing to come online, and a larger mobile clinic containing two procedure rooms and a waiting room was on the way to allow the providers to see more patients each day and make it possible to provide second trimester procedures.

However, Just the Pill Medical Director Dr. Julie Amaon told RNG that after being in use for about a year and a half, the mobile clinics have now been sidelined in favor of pop-up clinics.

“What we found is that working with community partners and spreading the love around, so to speak, moving around to different parts of the state to be able to provide services in different areas, worked just as well as using the mobile clinics,” she said.

One of the big hurdles for mobile clinics is parking.

“We’ve talked to a bunch of community partners that have been willing to have our medication mobile van, but anytime you start talking about a medical procedure, and medical waste, and the possibility of protesters, that increases your risk for your community partners as well,” Amaon said.

However, Just the Pill has always cited Plan A—an organization that provides a wide range of health services in mobile clinics in the Mississippi Delta—as a major inspiration. Just the Pill’s vision for the future has always included other services, like IUD and contraceptive implant insertions, Pap tests, and breast exams. Amaon still expects the mobile clinics to be useful in the future both for these types of services and for abortion care, once they can work out the kinks.

Amaon is in it for the long game.

“It took 50 years to dismantle Roe,” she said. Even in the event of a political victory, “it’s going to take us 25 years at least, maybe 50, to get back to where we are providing abortion care in your home state, in your hometown, with your primary care provider.”

Similarly, Planned Parenthood Great Rivers, formerly Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region and Southwest Missouri, launched a mobile clinic soon after the fall of Roe, but a spokesperson said it wasn’t used for abortion care as much as expected, in part due to the number of new clinics that opened up in Southern Illinois. However, the clinic remains useful for other procedures, including vasectomies, as recently demonstrated at the Democratic National Convention.

The one idea that took off

According to the Guttmacher Institute, nearly 1 in 5 U.S. abortion patients now travel out of state for care. And each new ban that goes into effect forces patients to travel farther. This means that more people are traveling by air, and thanks to a nonprofit called Elevated Access and its group of volunteer pilots, some of them are being flown on small, private planes at no cost.

According to Mike Bonanza, Elevated Access’ founder and executive director, most Americans live within 30 miles of a small airport. In the aviation industry, there was an existing practice of “angel flights,” where volunteer pilots would provide free help in situations ranging from domestic violence to natural disasters to accessing specialized health care.

Bonanza had been working on the idea of creating a volunteer pilot network to connect people with abortion care since Texas SB 8 went into effect in 2021. The organization launched a few months prior to Dobbs, and following the decision, interest from pilots exploded.

Elevated Access now helps clients obtain abortions and gender-affirming care. According to Bonanza, its pilots have flown over 1,600 people on more than 1,000 flights since 2022.

Pilots go through an extensive background check and vetting process. They provide their own aircraft and pay for all costs associated with the flight, including maintenance and fuel. Most of the planes are very small, with just four seats.

Bonanza worked closely with existing practical support organizations to make sure Elevated Access delivered services in a way that made sense. Partner organizations triage requests and generally send patients to Elevated Access when it isn’t possible to book commercial flights or other forms of travel.

Alison Dreith, director of strategic partnerships at Midwest Access Coalition, Elevated Access’ founding partner organization, said volunteer flights aren’t her first choice, but they are helpful when other options fall through. They’re also game-changing for those living in very rural areas, where commercial flights can either be inaccessible, extremely expensive, or require a level of triangulation that adds significant time to the trip—time that patients who are already missing work or lacking child care don’t necessarily have.

“It’s really rural people where, oh my gosh, we can’t even get them to the next village,” she said. “Where we can’t get a volunteer, we can’t get an Amtrak, we can’t get a Greyhound to pick these people up.”

A small plane flying from one small airfield to another can often fly a much more direct route than commercial options would allow, Bonanza said.

“Many of the people we transport have never flown before,” he added. In what may already be a stressful time, “imagine how intimidating and stressful it would be to try to navigate airline travel as a brand new person that’s never done it before. TSA is yelling at you to take off your shoes, and you’re like, ‘Why do I have to take off my shoes?’”

Of 1,500 pilots who expressed interest, Bonanza said 600 went through the Elevated Access application process, and 400 have been fully vetted to ensure not just their qualifications, but their full support for abortion access and gender-affirming care.

“I’m just so thankful that things like this can exist and hopeful that we can keep on innovating,” Dreith said. “It takes us all to put our heads together and share ideas and to build off those things.”

For now, it seems the most important intervention to help people access in-person abortion care was the most predictable one: financial and practical support for travel.