Pulling Back the Curtain on C-Sections and Childbirth

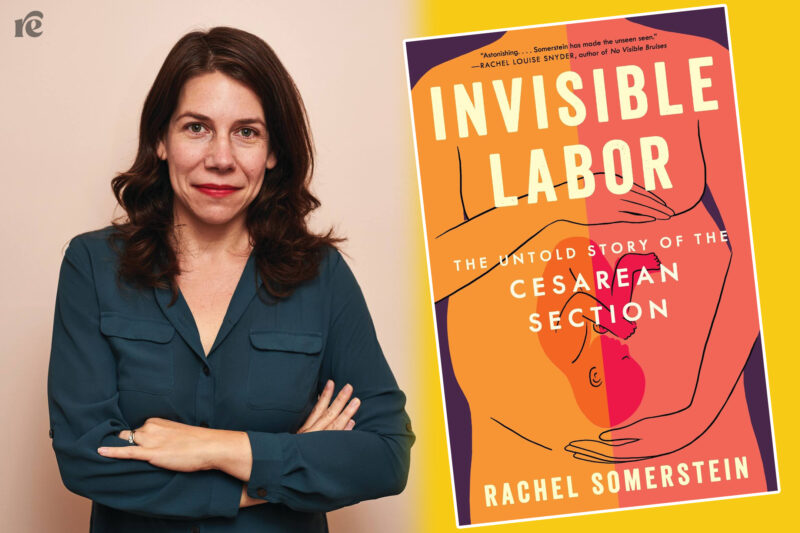

Author Rachel Somerstein's own birthing experience helps inform her new book Invisible Labor.

Cesareans account for almost one-third of U.S. births. Yet they are still an often misunderstood way to give birth—hidden behind the door of the operating room, an experience from which parents can emerge bewildered and profoundly unsupported. Invisible, in a sense.

From that idea comes a new book out today by Rachel Somerstein investigating surgical birth: Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section.

Somerstein, a journalist and professor at State University of New York at New Paltz, had PTSD from her own cesarean birth in 2016. Not only did she feel dismissed by the people caring for her during labor, but the anesthesia did not work during surgery—her searing pain continued even after she screamed for medical staff to stop.

Somerstein’s own experience informs and colors her book, but her important exploration into surgical birth goes well beyond the personal. Examining everything from the history of obstetrics to the financialization of health care to the way individualism impacts both our ideals and experiences of childbirth, Invisible Labor truly gets at the multiverse of factors that make up cesarean birth in the United States. C-sections are individual and systemic, a birth and a surgery, a monumental life experience and a common medical procedure.

Rewire News Group chatted with Somerstein about cesareans and reproductive choice, how to bring community back into birth, and who she hopes reads her book.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Rewire News Group: The impetus for Invisible Labor was your own traumatic cesarean, but your book covers a ton of history, culture, and context that goes well beyond your own experience. How did you get to the vast cultural history that this book ended up being?

Rachel Somerstein: C-sections are the most common operation in the world, and they are so undertalked about in our culture. As I continued to research and report for this book, I basically found that c-sections are a terrific lens through which to look at American society. We try to understand why we do so many of them. We try to understand why, for instance, Black women are more likely to have them. There are all of these aspects that include history, economics, sexism, racism, and more. It’s like turning over a stone. And you see, oh wait, there’s a whole series of connections there with aspects of American culture. Everything related to it is all so complex and multifactorial.

Can you talk a little bit about our current reproductive climate and how the issue of cesarean birth intersects with it? I’m thinking specifically about the Dobbs decision and what downstream consequences you see for birthing people, especially those who have already had or will have cesareans?

RS: It absolutely intersects. That’s the whole idea of reproductive justice. So we can’t just talk about birth and pregnancy on one side and then abortion on the other side. The emphasis on fetal “personhood” and the emphasis on preserving the life of the baby—even at the cost potentially of the mother’s life—is absolutely informing all of these laws and policies.

That bears out most clearly with access to VBAC (vaginal birth after cesarean). I think that the latest data is something like 1 out of 5 hospitals [from 2010] will not permit VBAC, and then obviously many more may “tolerate” it, but make it kind of impossible. Providers may seem like they are tolerant of the option too, but may not really be. In practice, that can look something you’re about 38 weeks and your doctor says, “I know you were interested in a VBAC but let’s get you scheduled for your c-section, OK?”

I read all of that through the lens of the climate regarding maternal autonomy, which is that we increasingly don’t grant it. Even the very fact that there are forced cesareans demonstrates that fetal life is more important than maternal life in this country. Of course, I want to make it clear that’s not the case with every single provider or every single institution, though.

States where abortion access is most limited are often the states with the highest cesarean rates. To me, that’s an underdiscussed consequence of these laws—that people that have already had multiple cesareans are going to continue to have cesareans, which then increases the health risks for both themselves and their babies.

RS: The refusal of maternal autonomy is evident in these states on both ends of the spectrum. It permeates in terms of trying to have the baby, trying to have it the way you want to (for example, trying to have a VBAC) or even being able to access midwifery care.

And it’s not just in states where abortion access is limited. Lack of access to general choices about how and where and with whom you birth is everywhere—it just shows that you can’t think of yourself as being saved by your geography or that this doesn’t matter to you because you’re carrying a dearly wanted pregnancy.

I was really moved by your realization of how much you would have wanted to have your community with you in your first birth. Do you think there’s a way to incorporate community more fully into birth as it is today, even and maybe especially cesarean births?

RS: First, really taking a moment to think about who you would want to have with you during your labor and birth. It should be someone who really believes in you, someone you know is not going to care about seeing you naked or whatever sounds you are making or if you poop. Friends or family who have been through birth may be willing. Don’t be afraid to ask!

For a c-section, what’s complicated about having people with you is that you’re in the operating room. There are doulas who specialize in cesareans, though. When I learned that, it blew my mind! Then I was like, “Well, why wouldn’t you have a doula for a c-section?” Everybody else who’s there is going to be focused on this primarily as a medical event, and a doula can be the person who helps you get comfortable, who advocates for you, if you’re feeling frightened or whatever happens.

I think that potentially hiring a doula for the actual surgical birth and then making sure you have your community after birth to the extent that you want it. Don’t be afraid to tell your family or your friends or community in advance about the things that would be helpful like, “please do my dishes,” or “you can stop by between 3 and 5 p.m.,” or “just sit on the sofa with me.” I had friends who did that, and that was so meaningful. They were coming for me. They weren’t just coming to hold the baby.

What do you see as some of the solutions to making birth better for people in the United States?

RS: Midwifery—greater access to it and also really integrating it. By that, I mean changing the entire outlook on maternal care towards one that is more oriented around midwifery than obstetrics. Moving towards the midwifery model of care would mean treating pregnancy and birth not as states of illness or disease or as potential catastrophes that can be avoided, but as a regular part of life. That’s one thing that would be transformative.

Another big part of integrating midwifery would mean making other changes at the systemic level, like allocating federal funding towards midwifery training and bringing midwives into positions of power within hospital systems so that they have voting rights. Some data shows that simply having midwives in a hospital lowers the c-section rate.

Another way is group prenatal care. I wish I knew about it when I was pregnant because the evidence really shows how effective it is at making birth better in terms of low birth weight, lowering the rate of unnecessary c-sections. And of course, people say they had a positive experience with it because they get the community aspect—they have a group of other birthing people who are going to these appointments with them. I think that could be really effective.

Obviously, there are other ways of dreaming of how to re-envision the United States health-care system, which I hope we do for everybody’s sake. I kind of came out of this book thinking, “Oh my God, we are in trouble because of the growing role of private equity.” The financialization of medicine is such a serious threat to our future.

What surprised you the most in your research and writing for the book?

RS: I was surprised in the ways that my own empathy grew, tremendously. I was surprised how most providers really want to do a good job and want to have a good outcome for everybody, truly.

I was also surprised at first by how many women spoke to who also experienced pain during their c-sections. Now, I’m not surprised when it comes up, but at first I was like, “Whoa, I’m not even looking for these people and they’re kind of falling out of the woodwork.” And now there’s data that’s actually coming out that’s saying it’s around 10 percent of c-sections where people do feel pain during the actual surgery and birth. I want to say the level of pain I had was unusual because I don’t want to scare people, but the overall phenomenon is not.

Who do you hope reads the book?

RS: I wrote it thinking about people like me who had traumatizing experiences and didn’t see themselves reflected in the stories of birth that are most widely circulated in our culture. So, I hope that people who want to feel less alone will read it and I hope that they actually will come out feeling less alone.

I hope they’ll finish the book and feel like, “This wasn’t my fault. I didn’t do anything wrong.” If you had a c-section that wasn’t planned or the c-section itself went in a way that caused you trauma or pain or embarrassment, there is nothing wrong with you. As long as c-sections have been happening, there’s always been major forces that have nothing to do with you that ultimately contribute to you having this surgery.