Anti-Abortion Centers Spent Over $600M in One Year. That’s the Tip of the Iceberg.

Documents reviewed by Rewire News Group suggest the total may have been closer $1 billion. Where is all that "crisis pregnancy center" money going?

“Crisis pregnancy centers,” or anti-abortion centers, are known for deceiving and manipulating people seeking information about abortion. They often pose as legitimate abortion clinics, intentionally obscuring their real purpose. They promote dangerous medical misinformation such as abortion pill “reversal.” They also discourage safer sex practices, and because few of them are actual medical facilities, they don’t adhere to medical standards for confidentiality and safety.

For example, a Massachusetts woman sued a CPC in June for failing to diagnose her ectopic pregnancy, which resulted in an emergency surgery and the loss of her fallopian tube. Months earlier, a Kentucky nurse came forward to reveal that a CPC where she had volunteered was failing to properly sterilize its transvaginal ultrasound equipment.

And CPCs’ activities are increasingly being bankrolled by the government. At least 18 states have funded them at some point. Since 2010, 13 of those states have given CPCs about $495 million. If you don’t see your state on the list, that doesn’t mean your tax dollars haven’t contributed: Many states use federal funds from programs like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families to support CPCs.

However, awareness of the harms that CPCs cause is on the rise. As a result, at least two states have cut off their flow of public funding. Twice, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has used line item vetoes to do so. In Pennsylvania, which became the first known state to fund CPCs in 1995, Gov. Josh Shapiro finally put an end to the practice this month.

But these reforms can only go so far. While taxpayer money has certainly been a boon for CPCs, many of them still get the majority of their funds from private donors. In fact, according to a 2020 report from the Charlotte Lozier Institute, an anti-abortion organization, “at least 90 percent of total funding for centers is raised through private donations.”

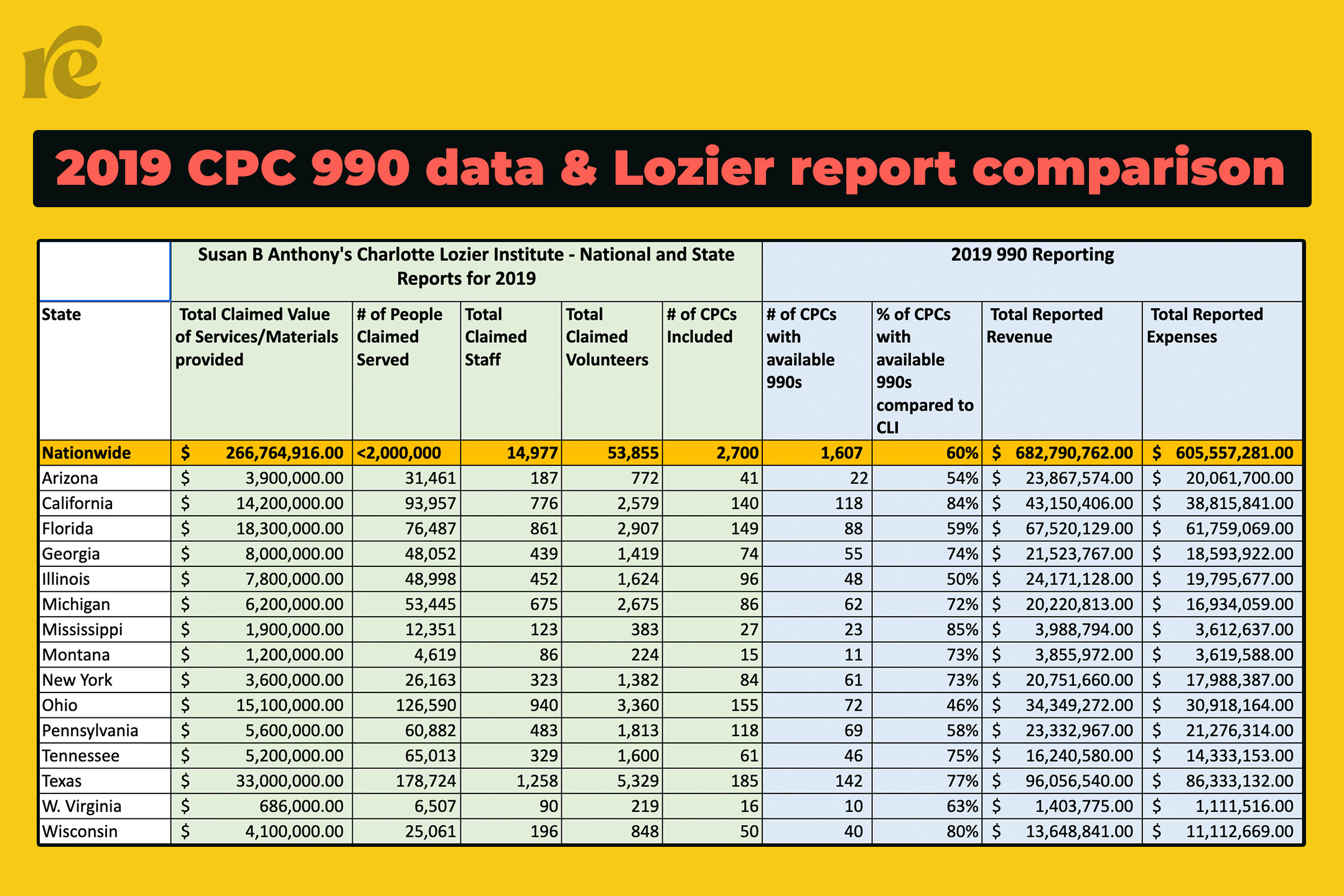

The total revenue reported by these 1,607 “crisis pregnancy centers” in 2019 was $682,790,762. They spent a total of $605,557,281.

The lack of transparency in private philanthropy makes it difficult to know who is funding anti-abortion centers, and what their money is used for. And we’re talking about a lot of money. Financial records reviewed by Rewire News Group indicate that nationwide, CPCs could be receiving and spending more than $1 billion per year.

On what, exactly?

$270 million or $1 billion?

There are independent “crisis pregnancy centers,” but most are affiliated with national religious organizations. The three largest in the space are Heartbeat International, Care Net, and the National Institute of Family and Life Advocates (NIFLA). Regardless of affiliation, CPCs vary significantly in their size and organizational structure. That, along with the fact that most CPCs are not licensed as medical facilities, makes it difficult to determine how many of them actually exist.

According to membership numbers cited by Heartbeat International, Care Net, and NIFLA, there may be close to 4,000 anti-abortion centers nationwide. However, in its 2020 report, the Charlotte Lozier Institute places the number at “more than 2,700 pregnancy centers.” Two other databases have identified slightly fewer: The CPC Map currently lists 2,555 centers, and Reproaction’s Fake Clinic Database lists 2,642.

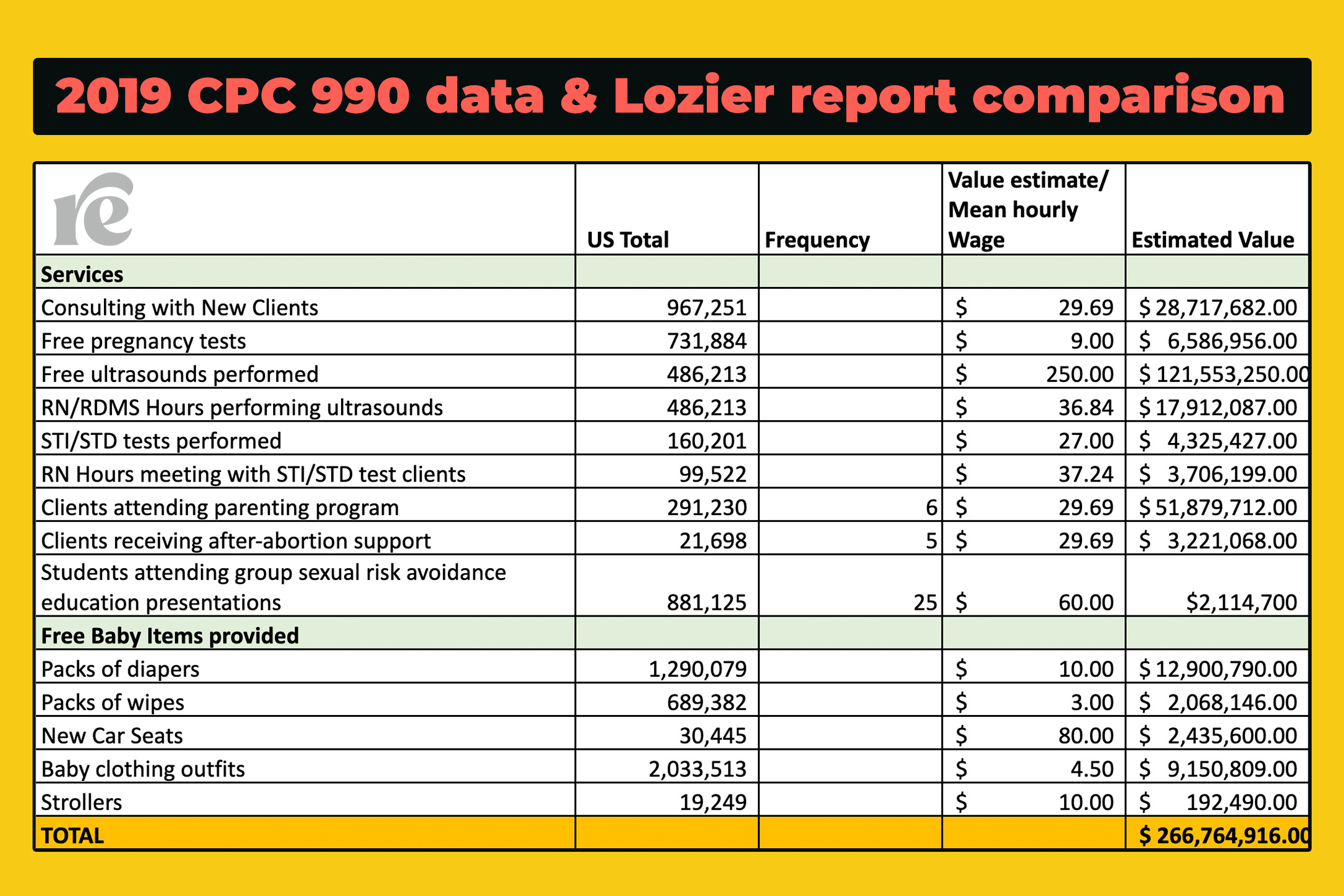

But let’s take the Charlotte Lozier Institute at its word: The Institute says its report includes data from 2,700 CPCs that served “almost 2 million people in 2019” and estimates the value of services provided to be “nearly $270 million,” or $266,764,916, to be exact.

Yet the estimated value of programs and services doesn’t tell us much about their actual cost, or about how much money these organizations really have. However, because CPCs are usually nonprofits, most of them—though not necessarily all—are required to file a Form 990 financial disclosure every year.

In an effort to get a better picture of CPC financials, Rewire News Group identified and reviewed 990s filed by 1,607 CPCs for fiscal year 2019. This represents only about 60 percent of the number of facilities included in the Charlotte Lozier Institute report.

The total revenue reported by these 1,607 CPCs in 2019 was $682,790,762. They spent a total of $605,557,281.

In other words, the actual amount of money spent by just a fraction of U.S. “crisis pregnancy centers” is more than twice the Charlotte Lozier Institute’s estimated value of CPC services. And if there really are closer to 4,000 CPCs nationwide, based on the average expenditure per facility, they could collectively be spending north of $1 billion every year.

“Free” isn’t free at a CPC

Clearly, the Charlotte Lozier Institute (CLI) report is not intended to provide a full accounting of CPC financials. It reads as a document meant to entice donors, to show how valuable CPCs are. This makes sense: The anti-abortion movement has framed CPCs—private charities—as a viable alternative to increased government spending on social services in the wake of Roe v. Wade’s demise.

Previous reporting by Rewire News Group found that Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, CLI’s parent organization, saw shoring up CPCs as a major element of its post-Roe plan.

But the CLI report—and the huge gap between its estimates and the actual amount of money CPCs have on hand—is further evidence that what CPCs claim to do is very different from what they actually do.

First, it’s important to understand that the CLI numbers are inflated to begin with. For example, according to the report, 8 in 10 CPC workers are volunteers. Only 12 percent of those volunteers have medical training, along with just 25 percent of paid staff. Yet CLI estimates the value of their labor by using median wages for skilled workers such as registered nurses, social workers, and diagnostic medical sonographers—a particularly egregious choice considering that ultrasounds offered by CPCs are generally “nondiagnostic.”

The actual amount of money spent by just a fraction of CPCs is more than twice the Charlotte Lozier Institute’s estimated value of CPC services. If there really are closer to 4,000 CPCs nationwide, based on the average expenditure per facility, they could collectively be spending north of $1 billion every year.

Parker Dockray is the executive director of All-Options, an organization that offers pregnancy options workshops; a free, unbiased pregnancy options talkline; a similar faith-based counseling line; and a resource center in Indiana that provides pregnancy tests, diapers, baby clothes, abortion funding, and more. In other words, All-Options does everything that CPCs claim to do.

And Dockray wants it to be known that non-medical volunteers and staff can be highly competent. In fact, many reproductive and sexual health clinics rely on peer counselors to talk patients through their pregnancy and contraceptive options. Most abortion funds are powered by volunteers. So the issue isn’t that people without medical education can’t provide high-quality services—it’s that they need to be properly trained to do so.

“Our Talkline advocates are peer counselors, but they’re good counselors because we train them well,” Dockray said. CPCs, on the other hand, typically use training materials that come from organizations like Heartbeat, Care Net, and NIFLA, which are rife with disinformation.

Another eye-popping figure from the CLI report: In a tally of material goods and services, the report claims that CPCs provided 731,884 pregnancy tests at a value of nearly $6.6 million. That’s $9 per test. While some digital pregnancy tests do cost that much, hospitals, clinics, and doctor’s offices use simple paper test strips. Anyone can buy those for less than 40 cents per test.

Could the CLI report be an attempt to represent the value of CPC services to clients? Certainly. But another well-known fact about CPCs is that the services they provide are usually limited—and come with strings attached. The CLI report even acknowledges that most centers use “an incentive-based approach.” That is, parents are “invited” to attend classes—which are typically religious in nature—to “earn points or ‘baby bucks’/CARE cash” that can be exchanged for items like diapers, wipes, baby clothes, and formula.

In other words, “free” isn’t free at a CPC, and the goods and services they do supply probably aren’t as valuable as the CLI report would have you think.

“A lot more questions than answers”

“When you look at CPC 990s, you come up with a lot more questions than answers,” said Jennifer Amuzie, movements communications manager at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, which was founded with the mission of making the nonprofit sector more transparent.

Last year, NCRP published a report based on its own analysis of CPC 990s, showing that CPCs reported a revenue of more than $4 billion between 2015 and 2019. NCRP also reviewed the 2019 data obtained and verified by Rewire News Group, which included details such as total staff compensation, government grants, and advertising and promotional expenses.

“If you look at all of the organizations’ staff compensation and then divide that by their total expenses, staff compensation made up about 50 percent of all the collective CPCs’ expenses,” said Stephanie Peng, NCRP’s movement research manager. “Looking at the top 20 or 30 organizations that spent the most on staff compensation, that made up well over 50 percent of their expenses.”

This is not an inherently bad thing—far from it, in fact. High staff compensation is often seen as a sign that a nonprofit is “inefficient” or “overspending.” But this is a flawed premise, according to Dockray.

“It’s based on this weird idea that charities only give away material goods,” she said. To the contrary, many nonprofits’ offerings are program-based, and for good programs, you need fairly compensated people.

However, the fact that CPCs are spending so much on staff compensation is another thing that flies in the face of how they present themselves: as small, scrappy, volunteer-run organizations.

Another standout data point is the sky-high value of CPCs’ assets—well over $800 million total among this small group. The average organization in this dataset has $515,454 in assets, but dozens have assets greater than $1 million. A few hold more than $2 million or $3 million. For most, this stems from owning the building in which they’re housed—but many have significant amounts of money sitting in the bank, too.

Numerous CPCs also share tax identification numbers with larger Christian charities. Often, this means they don’t have to file their own 990s. It’s impossible, therefore, to know what proportion of the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars spent annually by these organizations is funding CPC activities.

Finally, churches aren’t required to file 990s, nor are their “integrated auxiliary” organizations. Some CPCs may qualify for this exemption, freeing them from almost all financial disclosure requirements.

Opportunities for reform

Nonprofits are supposed to exist for the public good—that’s why they have tax-exempt status. With so many of their harmful and deceptive practices out in the open, why are CPCs even allowed to be nonprofit organizations?

Realistically, it’s just not likely the IRS could or would move to begin revoking CPCs’ tax-exempt status. But there are other opportunities for reform, starting with 990 reporting requirements.

While the Form 990 does require quite a bit of information, most of it is reported in aggregate. Nonprofits are required to report the total amount of money they spend on certain types of expenses, but in most cases, they don’t have to provide much detail.

For example, nonprofits must report whether they engaged in lobbying, which the IRS defines as attempting to influence legislation. Any nonprofit that engages in too much lobbying risks losing its tax-exempt status.

“An organization will be regarded as attempting to influence legislation if it contacts, or urges the public to contact, members or employees of a legislative body for the purpose of proposing, supporting, or opposing legislation, or if the organization advocates the adoption or rejection of legislation,” the IRS website reads.

Many CPCs report that they don’t engage in lobbying at all. However, given their large expenditures on advertising and promotional expenses, that seems doubtful. For instance, if there’s an abortion ban being debated in the state legislature, is a “Choose Life” sign lobbying? Or just an ad for a CPC?

And even beyond actual lobbying, “there are other forms of advocacy,” Peng said. “Just taking into consideration how prevalent CPCs are, and how far and wide they reach both digitally and physically, it makes me wonder how much of their money is really being spent on advocacy against abortion access.”

Reporting requirements that are too onerous could “take away from valuable time and resources that nonprofits need to be able to do their work,” Peng said. However, she does believe more specificity in 990 requirements would be reasonable and welcome.

“I think that would also help everyone understand where funding is coming from, and how money is being used,” Peng said. “It would also help highlight where gaps in resources and funding might be.”

What philanthropy can do

CPC 990s also reveal just how reliant they are on donor-advised funds. A DAF is an account established by a charitable “sponsor.” Individual donors can then contribute money to the account. Technically, once the sponsor receives that money, they have control over how it’s spent. But the individual “advises” the sponsor on where to make a contribution.

Essentially, DAFs allow individuals to make charitable contributions, with all the tax benefits that entails, while obscuring their identities. For big givers, it also eliminates the headache of establishing their own foundation. Numerous big banks and investment firms—Fidelity, Schwab, and Bank of America being among the largest—operate DAFs.

It’s not just “crisis pregnancy centers”: DAFs are an important source of donations for All-Options and many abortion funds, said Dockray. Any attempts to force DAFs to end contributions to CPCs, she worried, could result in abortion providers and support organizations being cut off, too.

“But there’s a lot of pressure for DAFs to be reformed, so that donors have to say who they are, and to reveal how much money they have,” Dockray said. “All of that I totally support.”

Peng agreed, referring to DAFs as the “big black box” of the nonprofit sector. In general, she said, philanthropists should be held accountable for the contributions they make. Bringing more awareness to CPCs and the harms they cause, she said, is a necessary move in that direction.

“There will always be anti-abortion funders who are just against abortion,” she said. “But I think that part of the reason that CPCs have been able to get so much funding is because of their deceptiveness. So I think the first step to really be able to address this is to fully publicize the deceptive tactics that they use.”

Beyond that, the most important thing philanthropy can do is stop beating around the bush and start focusing on abortion access.

“Funders need to be unapologetically doubling down on funding abortion access,” Peng said. “People’s lives are on the line, and funders are prioritizing their own legal safety, instead of those people whose lives are on the line, who can’t access services that they need. And that is really harmful.”