Editor’s Note: When It Comes to Teens Accessing Abortion, Whose Choice Is It, Really?

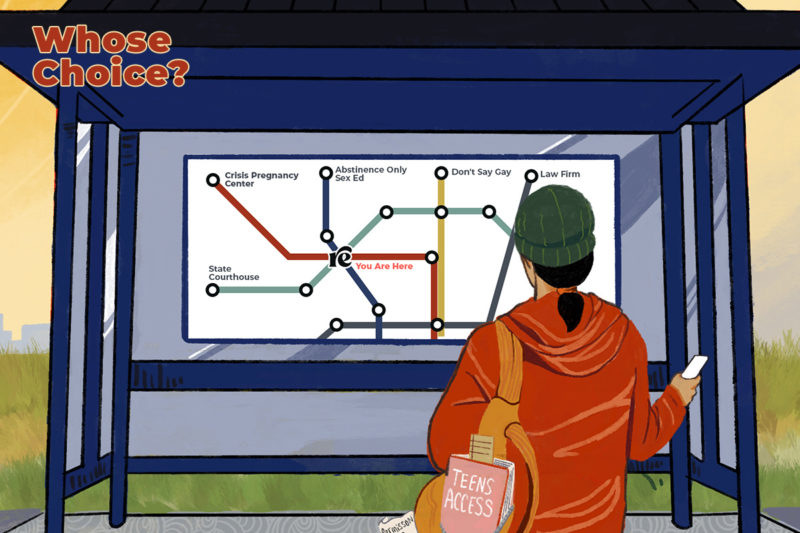

Whose choice is it to access an abortion if a parent, caregiver, or judge can block that choice? Just how much reproductive autonomy should teens have?

For more on teen access, check out our Special Edition.

Anti-choice lawmakers have made getting an abortion damn near impossible in most states. Mandatory waiting periods. Forced ultrasounds. Insurance bans on abortion. Gestational restrictions that arbitrarily cut off at what point in pregnancy an abortion can occur, sometimes before a person even knows they’re pregnant. Targeted clinic regulations that often force their closures, leaving many cities without any access at all. These are just a handful of barriers a pregnant person may have to negotiate to access their (as of now) constitutionally protected right to an abortion.

Now imagine that as part of solving that Rubik’s Cube of abortion restrictions you must also navigate the legal system. For teens and minors who need an abortion in this country, that’s precisely what many have to do.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, 37 states require some sort of parental involvement in a minor’s decision to terminate their pregnancy. That involvement can include notification that the minor is getting an abortion, consent for the minor to have the abortion, or sometimes both. For some young people who need abortions, parental involvement is not a barrier to accessing care. But it is for minors for whom parental involvement is not an option.

That’s why the Supreme Court ruled in 1979’s Bellotti v. Baird that states must allow for a process that permits minors to obtain abortions even when parental involvement is not an option. On the heels of the Court’s 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion nationwide, the Bellotti decision was seen as a well-intentioned compromise designed to ensure that minors maintain some level of their constitutional right to an abortion while also balancing parents’ rights to consent to medical care on behalf of their children.

What Bellotti unleashed, however, was a mess of bias and confusion. According to the Court’s ruling, to be constitutional, the process of judicial bypass must allow pregnant minors the opportunity to go before a judge, anonymously and with “sufficient expedition” to allow for a decision in time for a minor who is granted a judicial bypass to actually access the needed abortion. States have wide latitude in how much evidence of maturity they can require a minor to put forward to justify their plea for an abortion. Judges, too, have broad discretion in determining whether a minor is mature enough to have an abortion, which is how we end up with stories like this: a Florida teen denied an abortion because her GPA was too low.

There is not supposed to be room for that kind of arbitrary decision-making around fundamental constitutional rights, but that has always been the reality for minors in need of abortions in this country. Their entire existence is subject to debate and scrutiny like no one else’s, and with the Supreme Court poised—any day now—to reverse Roe v. Wade, minors seeking abortion care will face the highest hurdles to access in the months and years to come.

That’s why we devoted this Special Edition to exploring minors’ access to reproductive health care, including abortion.

Whose choice is it to access an abortion if a parent, caregiver, or judge can block that choice on a whim? Just how much reproductive autonomy should minors have? It’s a question reproductive rights advocates have been reluctant to grapple with, as Caroline Reilly explores the harms perpetrated by advocates’ unwillingness to push fully and forcefully for robust reproductive autonomy for minors—and how that failure has contributed to our current crisis.

Meanwhile, Imani Gandy has this retelling of Garza v. Hargan as a cautionary tale. In Garza, anti-choice advocates in the Trump administration tried to use the full power of the federal government to block undocumented minors in their custody from accessing abortion—in direct opposition to a court order granting the abortion in a story almost too wild to be true.

Except it’s not only true but also a dangerous harbinger of what’s to come in a post-Roe world if anti-choice advocates get their way. Did Garza v. Hargan help pave the way for Texas’ vigilante abortion ban when it allowed conservatives to pursue this idea of a third-party veto over some people’s abortions? There’s a good argument it did.

Where can minors turn for help accessing an abortion while also navigating the legal system? Advocates Graci D’Amore and Stephanie Kraft Sheley highlight a resource helping connect teens across state borders to do just that.

Finally, Jaclyn Friedman takes on the resurgence of the conservative “parental rights” movement and explains how the “school choice” movement often leaves many students unable to choose for themselves. It’s no coincidence, as Friedman explains, that Florida lawmakers are passing dangerous “don’t say gay” bills at a time when Oklahoma lawmakers are looking to require parental consent for birth control.

In Bellotti, the Supreme Court tried to strike a compromise on abortion rights and, in turn, served up a mess of injustice and abortion stigma for some of our most vulnerable patients. This seems like an important reminder as we await the Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization—a case that will likely uphold Mississippi’s patently unconstitutional 15-week abortion ban, which the media and many lawmakers have already framed as another “compromise” on abortion rights.

Who wins when abortion rights are framed this way? Certainly not pregnant people. And thanks to Bellotti, we don’t even need to wait for a ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health to know that to be true.