Abortion Was the Obvious Play to Turn Texas Red. How Did Democrats Miss It?

Decades of stagnation on abortion rights from Texas' ostensibly pro-choice political left led to the rise of restrictions—and the GOP amassing power.

This is the second in a three-part series; check out part one here, and come back next week for part three.

To understand the story of Texas SB 8, which went into effect six months ago today, and how we got here, we have to talk about George W. Bush and Rick Perry.

Despite being largely unqualified for the positions of power to which they aspired and later held, Bush and Perry, two profoundly careerist and deeply unprincipled men, managed to identify early on the right (and right-wing) anti-abortion coattails they needed to ride to carry them to political success.

In 1989, before he became famous for his hair, Perry switched parties from Democrat to Republican because he saw the winds of change coming in the Lone Star State. Bush never did much of anything (he was a bigwig in the Texas Rangers baseball franchise) before he traded on his father’s name—and his father’s anti-abortion politics—to move into politics.

Over the course of my research for this series, it became increasingly apparent that, despite literal decades of warning signs, gargantuan red flags, and Republicans’ outright statements of their intent to pass abortion restrictions at the first possible moment, many of the people who were best situated to protect abortion rights and access in the Texas Legislature—both before and during the rise of Bush and Perry—either neglected to do so, willfully chose not to, or openly assisted in anti-abortion efforts not over a few years or sessions, but over decades.

After all, if Rick Perry and George W. Bush could figure out that adopting the classism, racism, and misogyny of the growing, mostly politically unopposed anti-abortion movement in Texas could help propel them to success despite their demonstrated lack of personal and professional investment in anti-abortion principles, it is hard to believe no one saw these two clowns coming. Indeed, many abortion rights advocates and abortion providers on the ground repeatedly issued warnings that anti-abortion politicians and lobbyists were doing exactly what they said they were doing: trying to outlaw abortion by any means necessary.

But as the anti-abortion right became bolder and more assured, the ostensibly pro-choice political left in Texas, reluctant to take these warnings seriously, seemed to stagnate or even move backward, helping Republicans pass legislation that would open the floodgates for restrictions to come.

Texas targets young people

On January 22, 2000, the New York Times headline read in part: “With Help From Democrats, Bush Managed a Coup on Abortion Bill.” The Times published this story on the 27th anniversary of Roe v. Wade amid Dubya’s first bid for the presidency. It is an alarming piece of journalism that describes Democrats’ fecklessness in addressing the threat of the anti-choice movement in Texas.

The bill referenced is Texas’ 1999 parental notification law, which required abortion providers to notify a parent of an unemancipated minor seeking abortion care at least 48 hours before performing an abortion, or else the minor must navigate the courts in hopes of obtaining a “judicial bypass.” (Judicial bypass is a legal process that compels a pregnant minor to ask a judge for permission to get an abortion without informing a parent.)

In the piece, Democrats admit to helping Bush, who as governor pushed for Texas’ parental notification law to curry favor with the anti-abortion right and Christian evangelicals as he prepared for his White House. Texas House Democrats helped Bush nudge the bill over the finish line because, according to one unnamed lawmaker, they “like[d] him,” and because Democrats, who had already lost control of the Texas Senate, felt they would ultimately lose the battle anyway, so why cause a big to-do about it?

A former Planned Parenthood worker and Texas Democrat pooh-poohed concerns about Bush’s anti-abortion agenda, telling the Times that the bill was purely to “placate the religious right” because Bush wasn’t “strongly anti-abortion.” Another Democrat described the parental notification bill as both a “big loss” and a “nothing-burger” that “clearly had to be given to the religious coalitions.”

I doubt the young people who have been forced to expose their most intimate and personal experiences to strangers and judges in court or else carry an unwanted pregnancy to term would describe forced parental involvement and the judicial bypass process as a “nothing-burger” that “clearly” needed to exist for anyone, least of all “religious coalitions” or Bush’s political aspirations. But in light of the previous 25 or so years of Texas abortion politics, and with Texas Democrats largely viewing abortion rights as a subject to be avoided—or something to restrict—rather than actively expanded or protected, the dismissal of young people’s rights as inconsequential and immaterial to abortion rights more broadly makes a certain kind of sense.

And, of course, some Democrats reported getting some things in return for their support of the 1999 parental notification law: The Times notes that Bush was “willing to reward” those who helped him out, notably by not campaigning against “friendly lawmakers in the other party.”

In short, some Texas Democrats threw young people under the bus not to secure landmark progressive legislation or support for key left-wing initiatives, but in hopes of saving their own political asses. And for what? To live to fight abortion restrictions another day? Their records on that are pretty scarce, too.

The last time a Texas Democrat was elected to state office was in 1994; Democrats lost majority control of the legislature in the 1996 elections. The one piece of pro-abortion-rights legislation I could find from the mid-to-late ’90s was proposed by Democrat Ron Wilson, who in several sessions introduced a constitutional amendment “prohibiting the state from requiring a woman to complete a pregnancy.” His bill never made it out of committee.

It’s one thing to grow tired of a losing battle. It’s another thing entirely not to have entered the fight before it’s too late. And I think that, when the parental notification bill passed in 1999, it may have been in many ways too late for Texas. Not because we Texans as a people didn’t value reproductive freedom (we do and long have, just like the rest of the country), or because a few passionate, pro-choice Texas lawmakers and politicians never made it their business to support abortion rights and access. They did.

But because so much rhetorical, narrative, and political ground on abortion had already been ceded and seeded from day one of Roe, the case’s predication on a right to privacy was almost certainly flawed from the jump. The ink was barely fresh on Roe before the Supreme Court started to become openly hostile to abortion rights and access, and while political representation has very slowly improved over the years, the vast majority of early political decision-makers in Texas were (and continue to be) people who would never face an unwanted or untenable pregnancy.

More than anything else, Texas’ legislative record on abortion up until and including 1999 shows the fear of and even hostility toward affirmative, expansive reproductive rights. Seventeen abortion bills were proposed in the Texas Legislature in 1999, at that point the most ever in a single session. Just one—Ron Wilson’s proposal—supported abortion rights.

If those years in Texas politics had seen new, fresh-faced political leaders who were ambivalent about—or at least minimally motivated to pass—abortion restrictions, things might be different. But along came Dubya and Rick Perry, both of whom needed to wield little more than a good-ol’-boy charm offensive to meet the demands of an anti-abortion movement that never intended to stop encroaching on young people’s abortion access.

Of course, hindsight is 20/20, and perhaps abortion rights supporters in the Texas Legislature in the late ’90s and early 2000s could not have predicted how thoroughly the body would turn against abortion access, despite repeated warnings of the coming storm from abortion rights groups and the plainly stated intentions of anti-abortion politicians and lobbyists. Even so, it is hard to imagine looking forward at the time and predicting that, over the next 30 years or so, no Texas Democrat nor pro-choice anybody would be elected to statewide office, no matter how “friendly” they played with Bush.

Clearly, more than a few Democrats had bet on their bipartisan cooperation paying off politically. But if they hoped that supporting forced parental involvement laws would be the key to retaining Democratic seats in an increasingly Republican state, they were mistaken.

Instead, cooperation backfired into concession, and it wasn’t long before Republicans needed no help in passing Texas’ first omnibus anti-abortion law.

A new playbook in abortion politics—for both sides

If the abortion restrictions passed in Texas up to and including 1999’s parental notification law were incrementalisms, mere placations, and “nothing-burgers” meant only to shore up political careers, 2003 marked a dramatic shift in the anti-abortion playbook.

That year, Texas passed the “Woman’s Right to Know Act,” an expansive package of restrictions on abortion rights ranging from mandatory pre-abortion waiting periods to ambulatory surgical center requirements to forcing providers to share medical misinformation with patients seeking abortion care. States across the country would begin replicating those restrictions, as well, while anti-abortion sentiment grew stronger at the federal level, too.

Just after the 2003 Texas legislative session, Congress passed the “Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act,” which capitalized on decades of anti-abortion lies and fearmongering about the provision of later abortion care but was nevertheless championed by President George W. Bush, building upon his early success convincing Texas lawmakers to restrict abortion care for young people.

Meanwhile, Rick Perry had won the governor’s seat in Texas, and in the 2005 legislature, state lawmakers proposed 21 new abortion laws, eight of which would have repealed existing restrictions, expanded abortion access, or protected abortion rights—15 years after Gib Lewis suggested that “both sides” might try to propose 25 or 30 bills every session to influence abortion provisions in Texas.

Despite the eight bills filed in support of abortion rights and access and a slew of efforts by Texas Democrats to derail anti-abortion proposals, the 2005 Texas Legislature, by then under total Republican control, passed more abortion restrictions—a 24-week ban, plus a requirement that minors obtain parental consent, not merely notification, for abortion care—by tacking them onto other legislation as amendments. During that same year, Texas also created its “Alternatives to Abortion program,” a scheme directing public funds to religiously backed “crisis pregnancy centers” that exist to dissuade people from seeking or accessing abortion care.

Texas got a reprieve from further abortion restrictions in 2007 and 2009. The 2009 session in particular saw a surge of Democrats ride the enthusiasm for Barack Obama’s presidential candidacy into office, tipping the balance of power not quite back in favor of Texas House Democrats, but closer to it than Dems had seen in either chamber in a decade. Nearly 30 abortion bills were proposed between the two sessions, almost half of which were in support of either abortion rights and access or of basing the state’s sex education standards on medical science, not religious abstinence. Texas’ strongest champions of abortion rights and access gained steam, growing adept at heading off anti-abortion proposals and becoming more confident and vocal in their support for reproductive freedom.

It’s no coincidence that this new cohort of lawmakers were women and men of color who did things differently—and took threats to abortion access much more seriously—than the aging white men who’d dominated Texas abortion politics for the previous 30 years.

So what came next was no accident: the racist Tea Party backlash to Obama’s first term as the country’s first Black president.

The Tea Party takes Texas

Abortion supporters in Texas had already warned in decades prior that abortion restrictions were predicated on racism, classism, and misogyny; the enthusiasm with which a new wave of anti-abortion Texas lawmakers, many of them Tea Partiers, approached the 2011 legislative session exposed those warnings as truth all too clearly. Even though Texas’ white, mostly (but not always) male conservatives didn’t really have any lost power to reclaim in terms of abortion—remember, no affirmative expansions or protections for abortion rights or access had ever passed in the state—they nevertheless aggressively pursued further attacks on reproductive freedom.

Anti-abortion lawmakers, the vast majority of them Republicans, proposed 36 new restrictions on abortion in 2011, surpassing previous records as the most ever introduced in one session One new restriction passed: Texas’ mandatory sonogram law, thanks to an assist from anti-abortion Texas Democrats whose support was needed to bring the bill to a vote.

Texas also ratcheted up efforts to “defund” Planned Parenthood, drastically cutting state family planning funds to health-care entities affiliated with abortion providers, which in the long term would reduce access to preventive screenings and reproductive health care of all kinds for tens of thousands of Texans. (A number of these abortion restrictions seemed to be supported by dark-money groups like the American Legislative Exchange Council, which provides right-wing “model legislation” to conservative lawmakers.) One House bill in the 2011 session sought to mitigate the worst effects of the defunding measure; it didn’t make it to the floor.

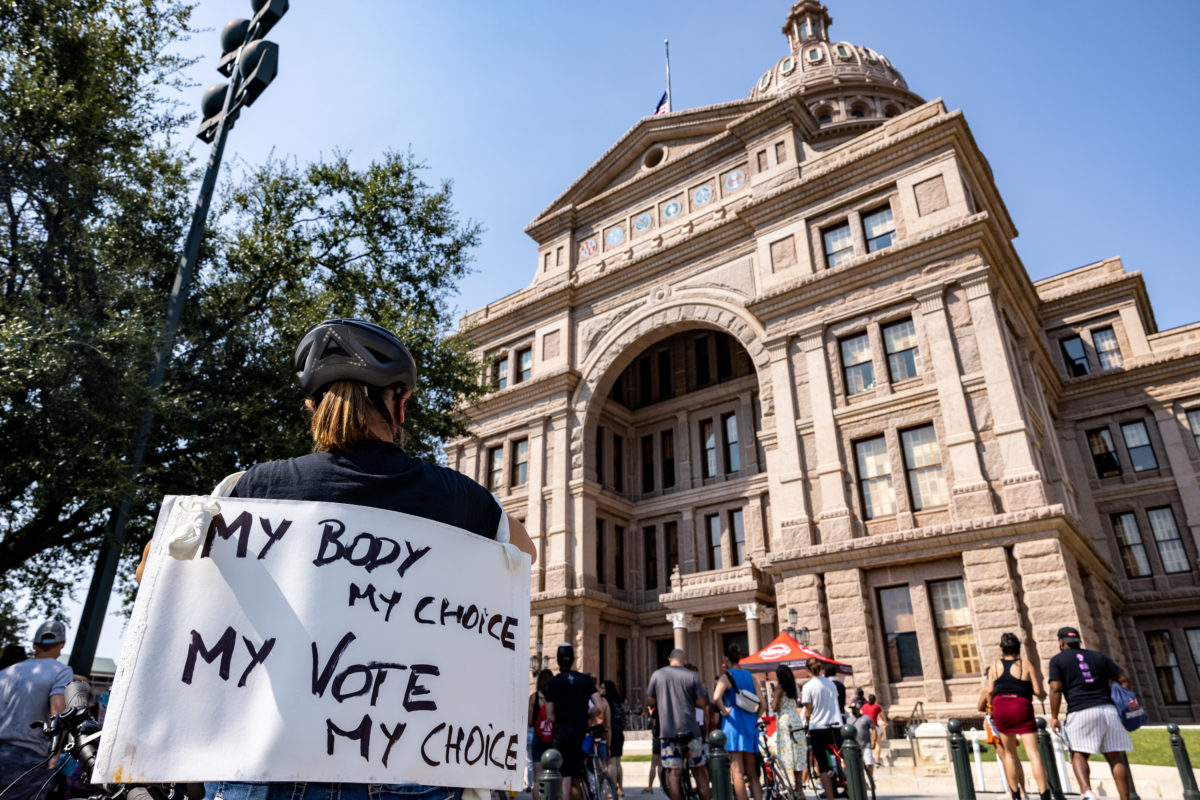

But as successful efforts to restrict abortion were ramping up, so too was a statewide political will in support of abortion rights and access. When the Texas Legislature convened again in 2013, it would see the state’s first real, all-out fight over abortion access, complete with a takeover of the state Capitol. The time for cooperation and concessions was over.

For more Texas SB 8 coverage, check out our special report.