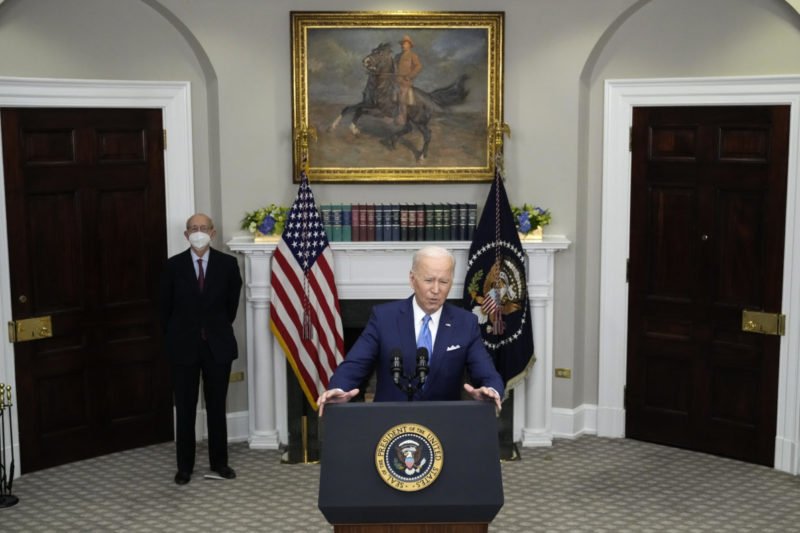

Biden Has a Chance to Make Up for the Disastrous Clarence Thomas Confirmation Hearings

Biden could have kept Clarence Thomas off the bench but didn't. Three decades later, he has a chance to prove that he is willing to do the right thing.

Angela Wright.

That’s a name you’ve probably never heard before. But it’s a name that should be as recognizable as Anita Hill’s. And Joe Biden is the reason you’ve never heard it.

As Anita Hill testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991 about allegations that then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas had harassed her during the 1980s—repeatedly asking her on dates and describing pornographic films in lewd and graphic detail—a woman named Angela Wright watched the proceedings with her attorneys in Washington, D.C.

Wright had worked for Thomas at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission as director of public affairs. She had firsthand knowledge of Thomas’ inappropriate and harassing behavior and was prepared to air it publicly. Investigators for the committee became aware of Wright’s allegations regarding Thomas’ actions and interviewed her over the phone. She was later subpoenaed to appear before the committee, where she was expected to corroborate Hill’s claims by testifying about Thomas’ pattern of harassing behavior when she worked for him, including one time that Thomas had asked her about her bra size.

But the Senate Judiciary Committee—of which Biden was chair—never called her to testify. And in the end, after she refused the committee’s request that it be allowed to portray her as a recalcitrant witness who got cold feet, Biden read a statement by Wright into the record with little fanfare in the press, according to Steve Kornacki’s comprehensive recounting of the Thomas affair, published in Salon in 2010.

Wright would later state in a 2007 interview with Michele Martin that Thomas had perjured his way onto the Court.

Lillian McEwen is another woman whose name you’ve never heard before, again because of Joe Biden.

McEwen, a former assistant U.S. attorney, dated Thomas for years in the late ’70s and early ’80s. But she was never asked to testify. Biden had decided to limit the witnesses for the confirmation hearings to people who had a professional relationship with Thomas. And even though McEwen would have been able to corroborate Hill’s accusations, Biden didn’t call her before the committee because her relationship with Thomas was personal, not professional.

In 2010, McEwen broke her silence about Thomas’ sexual proclivities.

“He was obsessed with porn,” she told the Washington Post. “He would talk about what he had seen in magazines and films, if there was something worth noting.” (If there was something worth noting? There’s never anything in an adult film worth noting to a woman who works for you.) McEwen also recalled a time when Thomas, who would tell her about women he encountered at work and was particularly “partial to women with large breasts,” told her he’d asked a woman her bra size. Was Angela Wright that woman? She told committee staffers during her phone interview that Thomas had asked her what her bra size was. Did Thomas expressly relay his sexual harassment to his girlfriend at the time? The public never found out because Biden never called either woman to testify. McEwen has said she didn’t want to wander into the political fray at the time, and Biden’s seemingly arbitrary decision to limit witnesses to people who knew Thomas professionally meant she was never approached.

During his confirmation hearings, Thomas remarked, “If I used that kind of grotesque language with one person, it would seem to me that there would be traces of it throughout the employees who worked closely with me, or the other individuals who heard bits and pieces of it or various levels of it.”

Those three women were the traces of it. Perhaps their stories didn’t carry much weight on their own. But together, they likely would have kept Thomas off the bench.

That’s Biden’s fault.

Kornacki’s 2010 report makes a convincing case that Thomas did all the things Hill said he did—and more—and argues that acknowledging all the facts is critical.

Biden acknowledging that truth—whether in a public announcement or a private reckoning—would position him to ensure that the forthcoming confirmation process for his own nominee goes smoothly. After all, he understands the bad faith and gamesmanship that inevitably occurs, particularly when it comes to nominees of color. He was vice president when Barack Obama nominated Sonia Sotomayor, prompting a racist deluge of commentary regarding her Puerto Rican heritage.

One hopes that in the 30 years since Thomas’ confirmation hearings—and given that he had a front-row seat for Sotomayor’s—Biden came to understand the credibility limitations any Black woman he nominates will be saddled with. The stereotypes about a lack of qualifications, about being a diversity pick, about being unsuitable for a seat at the table due to an inability to separate their race and gender from their jurisprudence—as if any white man is ever asked whether they can rule impartially in a world built for them and ruled by them. Biden ignored red flags, and as a result, we have someone who likely sexually harassed multiple women who worked for him sitting on the bench.

All of this is to say that, with his upcoming Supreme Court nomination to fill Justice Stephen Breyer’s seat, Biden has an opportunity for redemption. To make up for the fact that a legal titan and civil rights giant like Thurgood Marshall was replaced with a petty man who does not seem to inhabit the world the rest of us do. (He also, according to Jane Mayer’s recent New Yorker article, seems to be translating his wife Ginni’s right-wing antics into law without repercussions, since there’s no code of ethics that governs Supreme Court justices’ behavior.)

Biden also has an opportunity to cement his legacy as one of the most consequential presidents the country has had, not because of his historic infrastructure bill but because of the significance of his place in history when it comes to the politics of race.

This is a man who spent eight years playing hype man to the first Black president. Acknowledging that political theater can be powerful, it’s hard to deny the relationship between Biden and Obama seemed genuine. And in my experience, it is rare to find a white man who is not only willing to play second fiddle to a Black man but who also does it with such aplomb. There wasn’t the jockeying of power one would expect in a relationship like theirs: One can imagine a House of Cards episode—or perhaps an episode of Veep—in which Biden plots behind Obama’s back to undermine him and wrestle away power.

That didn’t happen, though. Instead we got jovial “Uncle Joe,” who made silly gaffes about Obama signing the Affordable Care Act into law being a “big fucking deal.” Then, after a four-year hiatus from politics, he runs for president, wins the Democratic primary, and picks a Black woman as his running mate. And now he has an opportunity to appoint the first Black woman to the Supreme Court. There’s a lot of Blackness swirling around Joe Biden, and that’s not a bad legacy to leave behind: VP to the first Black president. President with the first Black woman VP. And appointing the first Black Supreme Court justice. Impressive.

But that legacy will be soured if he thinks social justice-minded Black folks will be mollified by a centrist candidate like J. Michelle Childs. He can’t undo his failure to fully vet Clarence Thomas, or his failure to believe the Black women—Hill, Wright, McEwen, and others—who sat ready and, in most cases, willing to talk about who Thomas actually was.

He can begin to make it right by nominating a progressive Black jurist in the style of Thurgood Marshall, not a centrist candidate being propped up by Lindsey Graham.

And he can make sure the White House protects the nominee from the bad-faith, racist, and sexist attacks that are sure to be the hallmark of the confirmation proceedings.

Biden has to know this confirmation process cannot be business as usual. The hearings for Biden’s nominees of color to the federal judiciary have been difficult because Republicans have given all his appointees of color a hard time. Just last month, Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) tried to disqualify Andre Mathis, one of Biden’s nominees to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, claiming Mathis had a rap sheet. The rap sheet? A few speeding tickets.

He can’t let that happen this time. He has an opportunity to demonstrate a deeper understanding of his actions 31 years ago, how they shaped the nation and unleashed a wave of conservative jurisprudence that favors nothing but corporations and cisgender, heterosexual white men. This cannot devolve into another “Lucy and the football” situation. If Biden must proceed without bipartisan support to ensure that a progressive Black woman ascends to the bench, that’s what he should do. He must proceed like this is the most important decision of his presidency, Republican obstruction be damned.

Because in a very real sense—given the role the new justice will have in crafting dissenting opinions that, hopefully, will become majority opinions for future generations who are able to wrestle democracy back from neo-fascism—it is.