World’s Largest Catholic Health System Wants to Close D.C. Hospital That Serves the Poor (Updated)

Even as Catholic hospitals have moved away from serving the poor, they have adhered to other sections of the Catholic directives that curtail access to abortion, contraception, tubal ligations, vasectomies, gender transition-related care, and some fertility treatments.

![[Photo: A group of nurses protest Providence Hospital's closing]](https://rewirenewsgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NNUprovidencephoto-800x533.jpg)

UPDATE, December 5, 4:30 p.m.: Following public outcry over the proposed closure of Providence Hospital, the D.C. Hospital Association said Providence Hospital will continue to operate its emergency department for less severe conditions through April 30, according to the Washington Business Journal.

Providence Hospital opened under President Abraham Lincoln to fill a gap in care after the government reconnoitered Washington, D.C.’s only other hospital for use during the Civil War. The Sisters of Charity who ran the facility cared for the sick “not for the sake of compensation but as a religious duty,” the National Intelligencer reported at the time.

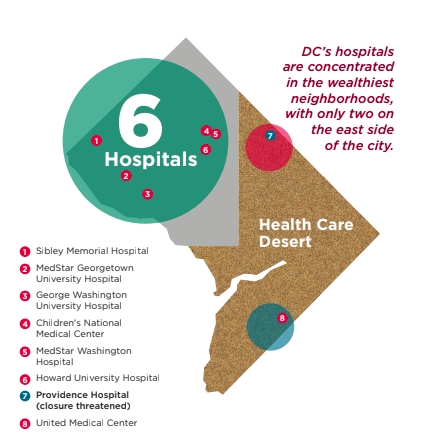

But 157 years later, the world’s largest Catholic health system, which operates Providence, plans to shut down acute-care services at the hospital, leaving a swath of eastern D.C. with just one hospital.

Catholic and union leaders have accused Ascension of abandoning its religious mission to serve poor patients. Providence serves some of D.C.’s poorest neighborhoods; 86 percent of its patients are on Medicare or Medicaid. But some advocates call this yet another example of how Catholic hospitals, which control one in six acute-care beds nationwide, operate like any other big business—even as they use their religious mission to deny reproductive health care.

“I know there’s frequently an argument that religiously sponsored health systems have a special mission and answer to a higher power, but in this case the higher power really is the bottom line,” Lois Uttley, founder of MergerWatch, told Rewire.News.

Despite its stated mission of “serving all persons with special attention to those who are poor and vulnerable,” Ascension appears to serve far fewer low-income patients systemwide than Providence. Less than a third of Ascension’s patient revenue comes from Medicare and Medicaid, compared to more than half of Providence’s, according to a MergerWatch analysis of data from Definitive Healthcare. Nearby hospitals have said they will be unable to absorb Providence’s patients. If the hospital closes, “I believe that a lot of these people would be lost and I think a lot of these people would die,” Elissa Curry, a Providence nurse, told Rewire.News. As a Catholic, Curry said Providence’s mission of serving the poor is important to her.

“I think Providence has always done that, but I think just recently, since this whole thing has come about with Ascension, I think they’ve lost sight of that mission,” Curry said.

Ascension’s CEO, Anthony Tersigni, made close to $14 million in 2015 and the company made more than $11 billion in the first half of this year alone. Last year, Ascension closed Providence’s labor and delivery unit, and in August it fired three-quarters of the hospital’s board after protests over its planned closure. But Ascension says it is simply shifting resources from inpatient to senior and behavioral care.

“Health Systems across the country are struggling to remain profitable as patients’ needs shift from inpatient to outpatient services,” Patricia Maryland, the president and CEO of the company’s delivery division, said in testimony before the D.C. State Health Planning and Development Agency on Friday. The D.C. Council in October gave the agency authority to approve the closure of any health-care facility.

Ascension has moved aggressively into outpatient care, which may be cheaper to provide; in addition to 129 hospitals, the company owns or manages 141 physician groups, 128 imaging centers, 79 urgent care clinics, 47 rural health clinics, and 41 ambulatory surgery centers, according to MergerWatch’s analysis.

“There’s two conflicting missions at work here: One is their religious mission, which includes service to the poor, and the other is the business mission, to stay financially sustainable,” Uttley said. “Unfortunately, with Providence Hospital, you’ve got a conflict of those two missions and it’s pretty clear that the business mission has won out.”

Directives for Catholic hospitals issued by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops include “the biblical mandate to care for the poor.” But nationwide, just 2.8 percent of Catholic hospital revenue goes to charity care, versus 2.9 percent for other religious nonprofits, and 5.6 percent for public hospitals, a 2013 analysis found. Even as Catholic hospitals have moved away from serving the poor, they have adhered to other sections of the Catholic directives that curtail access to abortion, contraception, tubal ligations, vasectomies, gender transition-related care, and some fertility treatments.

At an Ascension facility in Milwaukee last year, for example, a doctor told Rewire.News she was forced to watch a patient sicken, then labor for more than 24 hours until her lips lost color, because of the hospital’s Catholic prohibition on ending a pregnancy until a person is severely ill. That hospital, Wheaton Franciscan-St. Joseph, is located in a predominantly Black and low-income neighborhood. Ascension had planned to gut services there, too, but backpedaled after criticism. Nationwide, women of color are more likely to give birth in Catholic hospitals like St. Joseph where restrictions on care can put their lives at risk.

Catholic health systems like Ascension have managed to thrive in a landscape of consolidation that has seen many hospitals close. From 2001 to 2016, the number of acute-care hospitals that are Catholic owned or affiliated grew by 22 percent, while the overall number of such hospitals dropped. The reach of Catholic systems could grow even wider if Dignity Health and Catholic Health Initiatives follow through on a plan, approved by the Vatican, to merge into a single entity called CommonSpirit Health. The resulting company would be even larger than Ascension; the California Department of Justice conditionally approved the merger on November 21.