America, the Mythical: “Mother of Exiles” or Denier of Safe Haven?

Thanksgiving has been marshaled in the battle over what is the proper interpretation of the idea of America. With thousands of refugees looking for amnesty in that “last, best hope of earth,” will the better angels of our nature find room for them at the table?

The following essay was first published by Religion Dispatches for Thanksgiving of 2015. Since that time, the issues outlined here concerning America’s ambivalence about refugees, its contested identity, and the role of a founding mythology have only become more divisive and inflammatory. – eds

In a quiet part of the London borough of Southwark, on a street running parallel to the Thames, there is an old, dark-wood paneled pub with leaded windows. Formerly known by the borderline obscene name of “The Spread Eagle,” this is the oldest tavern on the river and it’s hard to go there and not imagine what it must have been like centuries before. Four centuries ago it was the favorite of a sea captain named Master Christopher Jones, who may have enjoyed a pint of bitter or a glass of sack on that same tide-beaten, mossy wooden deck that constitutes the bar’s back porch and where modern-day office-drones now get drunk.

Captain Jones was made rich by importing wine from France aboard his ship, but one day in the summer of 1620 he took on a very different cargo—a group of separatists who hired him to transport them away from England. Today the pub bears the name of that craft—”The Mayflower Pub“—and a copy of the famous compact written aboard that vessel is framed above the establishment’s urinal for any intoxicated customer to peruse.

It would, perhaps, be just as well to say that the Mayflower Pub in London is the place where “America was born” as Plymouth Rock in Massachusetts.

Of course there is no real moment when “America was born.” That a pub in South London is as suitable a christening place as a beach in New England speaks to the arbitrary power of myths. As concerns the religious separatists of 1620, legend can be as potent as fact.

The pilgrims, and later the Puritans, constitute an origin mythos for American identity. The pilgrims were Christian, but in many ways we have made the pilgrims themselves characters in a new faith. The New England settlers constitute both the Genesis and Exodus of the American scripture. The pilgrims are celebrated as the originators of the American ideal, embodying religious liberty, thrift, industriousness and individuality. Historical fact is secondary to mythical power. The Mayflower leader and first governor of the Plymouth Colony William Bradford, among others, saw Catholic figures like the Pope as the Whore of Babylon, a false prophet and anti-Christ sitting on the throne of St. Peter.

Yet today school kids, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, dress up in black construction-paper hats with fake buckles on their shoes and share plastic Thanksgiving feasts with equivalently accurate “Indians.” It is simply a sacrament in our national religion of Americanism, in spite of who the actual pilgrims may have been.

But if the idea of America is a religion of sorts, it embraces, likewise, fundamentalists and progressives, orthodox and modernizers. At their best, national myths create a unifying and hopeful story, but misapplied they sow division.

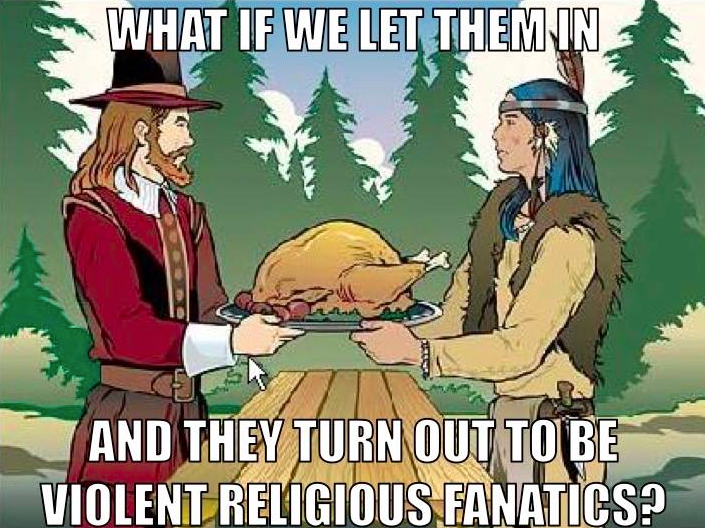

You may have recently seen some of the internet memes which mark the perverse irony of conservative Americans celebrating Thanksgiving—a holiday that calls to mind that group of refugees that started it all—precisely at the same moment that those conservative Americans wish to deny Syrian refugees a safe haven in the U.S. Of course the arrival of the pilgrims was disastrous for the indigenous population. But if we read the pilgrim narrative through the logic of myth and not history, we see a deeper truth of what that story has come to mean in American civil religion.

You may have recently seen some of the internet memes which mark the perverse irony of conservative Americans celebrating Thanksgiving—a holiday that calls to mind that group of refugees that started it all—precisely at the same moment that those conservative Americans wish to deny Syrian refugees a safe haven in the U.S. Of course the arrival of the pilgrims was disastrous for the indigenous population. But if we read the pilgrim narrative through the logic of myth and not history, we see a deeper truth of what that story has come to mean in American civil religion.

At its core this is really a debate about the interpretive significance of the mythic story of America’s foundation. The conservative reads a tale about Anglo-American Protestant hegemony and the opening up of North American resources. But the radical, perhaps even the mystical interpreter, reads a more allegorically profound story about America as “Mother of Exiles,” a universal space that encompases all ethnicities, cultures, and religions precisely because of its universality.

Arguments about the significance of the pilgrims began scarcely before the surf could erase the fresh footprints of the settlers on the beach at Cape Cod. The Puritans of New England were arguably among the most educated people in the history of the western world. Drawn from an upwardly mobile yeoman class, and populated by ministers, scholars, and merchants, they were some of the most unlikely candidates to forge a new civilization in the frontier wilderness. Yet their propensity to interpretive obsession led them to be their own first chroniclers, none more so than Bradford in his Of Plymouth Plantation.

Initially the symbolic import of their American locale was less important than the fact that they had garnered a degree of independence from the official English church, but over the course of the seventeenth-century their new home at the terminus of the western world took on a profound typological importance. As the historian Sacvan Bercovitch wrote, the Puritans eventually “identified America as the new promised land, foretold in scripture, as preparatory to the Second Coming.”

It was at the end of the seventeenth-century that the second and third generation of the initial Great Migration began to more fully understand itself as exceptional, as the descendants of a godly remnant who had escaped the Babylon of England and were now forging a new people in the forests of America. If Bradford saw himself as escaping from an England poised on perdition, those that came after saw the “American” as a new type of man.

Indeed during the 1660s the colonists who now numbered in the many thousands were traumatized by both the collapse of the godly Republic in Commonwealth England, and the almost apocalyptic violence of the King Phillip’s War with the Wampanoag Indians, necessitating the construction of a new identity separate from that of their mother country. It’s around this time that men like Cotton Mather began to refer to white settlers as “Americans,” a designation which other colonial powers such as the Spanish and French, and indeed English settlers in the South, reserved exclusively for the Indians.

For a long time there was an ambivalence about the Puritans. Indeed their own intellectual descendants—the New England transcendentalists and the radicals of the American Renaissance—viewed their inheritance with a wary eye. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was in the line of the dreaded Judge Hathorne of Salem witch trial fame (and whose notoriety was the reason for the author’s addition of a “w” to his own name), said that he was proud that the Puritans once existed, and relieved that they no longer did.

And yet during the horrors of the Civil War, the pilgrims took on a new symbolic role, as Yankee historians conceptualized the origins of America not in Jamestown, Virginia (which after all predated the pilgrims by thirteen years) but rather on the beaches of New England. As historian Jill Lepore writes “One American abolitionist, writing in 1857… implied that we ought to ignore 1607 and instead pay attention to the divided nation’s twin founding moments.” The other partner in this twinned pair of national origins was the sale of twenty Africans by Dutch slave traders to the English colonists at Jamestown a year before the Pilgrims would land at Plymouth.

For the New England abolitionists, the pilgrims were to be contrasted with their southern countrymen in what constituted a sort of Paradise Lost of American beginnings. The south may be older, but it was founded on a legacy of slavery as opposed to the tradition of liberty in the north. It was actually a view shared by Confederate sympathizers who saw southern culture as a colonial outpost of European civilization in opposition to the religious radicalism which characterized New England.

Yesterday, on November 24, viewers had the chance to see how modern scholarship understands colonial New England in the stunningly produced PBS documentary The Pilgrims (you can watch it here for a limited time). Like its forerunners in the American Experience series, the episode does have a tendency towards myth-making, but it’s aware of the artifice of that process, and all that that process implies. Bolstered by appearances from seminal historians of early American culture and literature like Bernard Bailyn, John Demos, and Jill Lepore, the documentary doesn’t shirk its responsibilities in presenting the most pertinent scholarship, even if it does engage the rhetoric of hagiography in its depictions of Bradford and other Plymouth leaders. As the literary critic Kathleen Donegan says in the documentary, men like Bradford understood that for Plymouth the “future was in its history” and the process of mythologizing events was central to them, a process which we’re still a part of, as the documentary itself demonstrates.

In claiming that the pilgrims and the stories we tell about them are largely mythic, I understand that many may take this as a condemnation, but this itself betrays an anti-mythic aspect of contemporary culture. There is no error in myth as long as we are aware that myth is what we’re trading in. The Spanish have El Cid, and the French The Song of Roland; we have Of Plymouth Plantation.

At its most potent, myth is a variation on the old adage that art is a lie which tells the truth. What we say about the pilgrims conveys allegorical knowledge of American character, and as we have refined the story we’ve seen how those settlers embody our own contradictions. America has been variously prefigured as a New Israel and a New Babylon, as Eden and Golgotha, as site of Genesis and Revelation. Formulated honestly, our myths can remind us of these contradictions. Just as the first Thanksgiving celebrated a moment of peace between the Wampanoag and their chief Massasoit, we also remember that 45 years later his son Metacomot had his head erected on a pike at Plymouth following the conclusion of King Phillip’s War. The settlers subsequently decided that that impalement also warranted a similar declaration of general thanksgiving.

As Leonard Cohen sings of America’s covenantal ambivalence, this land is “[t]he cradle of the best and of the worst.” Thanksgiving has been marshaled yet again in the battle over what is the proper interpretation of the idea of America. With thousands of Syrian refugees fleeing both the horrors of daesh and al-Assad, looking for amnesty in that “last, best hope of earth,” will the better angels of our nature find room for them at the table?