Mike Pence Neglected This Poisoned Indiana City. Now, Residents Fight for Each Other.

For decades, East Chicago has been home to heavy industry that poisoned the city. But is also home to thousands of people, many of whom have illnesses likely caused by that pollution.

![[Photo: Maritza Lopez sits in a recliner, smiling and holding her three dogs.]](https://rewirenewsgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/MaritzaDogs3-800x533.jpg)

When Maritza Lopez was about 18, her teeth began to fall out. They cracked apart, leaving shards in her gums that she extracted with tweezers. By her early 30s, most of her teeth were gone, and she was fitted for dentures.

Lopez is, in her words, a “rotten coconut”—a mess on the inside but good-looking on the outside. In an interview at her home in April 2017, her skeletal, 108-pound frame seated in a recliner, Lopez gestured toward a cascade of orange prescription bottles. “That’s me, and I’m only 53,” she said.

She produced a creased copy of her medical history, which listed 23 medications and some 40 conditions, including cancer, irregular heart rate, severe spinal problems, rheumatoid arthritis, seizures, headaches, and brittle bones.

The list doesn’t include the family members she has lost to illness.

While there’s no way to prove it, Lopez believes these ailments, and the premature deaths of her loved ones, stem from where she has lived since infancy: an area of East Chicago, Indiana, contaminated with lead, arsenic, and other heavy metals. Some 80 percent of East Chicago, which is predominantly Black and Latino, is zoned for heavy industrial use. Factories made lead products here for decades; steel mills and oil tanks still blot the landscape.

Although federal and state officials knew about lead contamination in East Chicago in the 1980s, it took until 2009 for the area surrounding the former USS Lead plant to be added to the Superfund National Priorities List of most-contaminated sites. And it took even more time for officials to act with any speed. Part of the reason may rest with a 2011 federal report that found there was no health threat from the air, water, or soil around the Superfund site. The Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) cited the findings of this report when Rewire.News asked about the agency’s apparent failure to respond with urgency to the contamination. But in September 2016, Reuters found the report was based on flawed or incomplete data and was, in the words of one expert, “embarrassingly bad;” the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry released a new report this August.

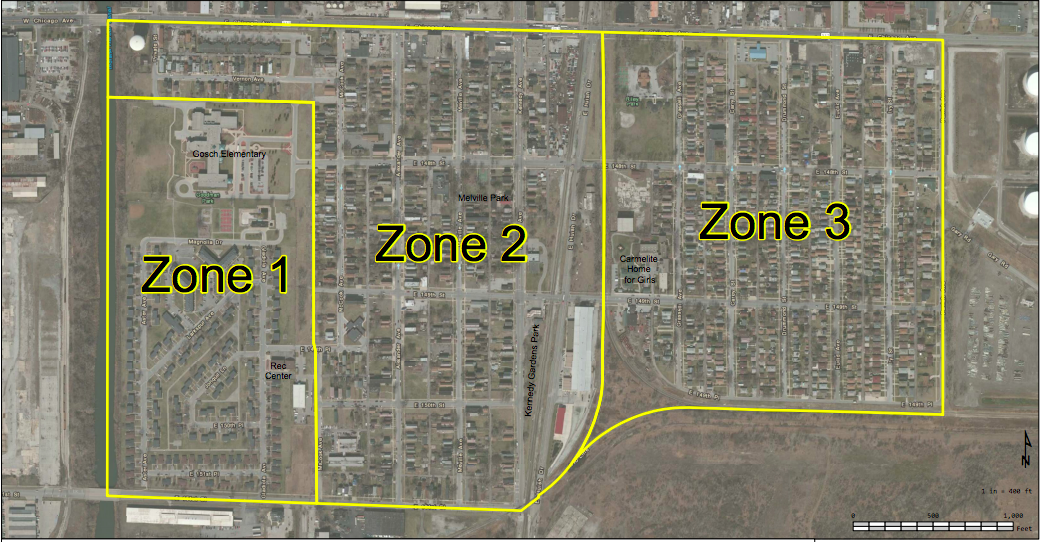

It confirmed that young children in two contaminated areas of East Chicago were nearly three times more likely to have elevated lead levels than children in other parts of the city. In a public housing complex that was built in the 1970s on a former lead smelter, and an adjacent residential neighborhood—Zones 1 and 2 of the Superfund site, respectively—about 28 percent of children tested between 2005 and 2015 had lead levels at or over the federal threshold for intervention. Most of those children were Black.

To residents, the report underscored the longstanding failure of officials to act on evidence that children were being poisoned.

“My first comment was that it’s not even worth the ink they wasted to write the report,” Lopez, who lives in Zone 3 of the Superfund site, told Rewire.News, referring to her remarks at a meeting where officials presented the report.

Many people were unaware of the contamination until July 2016, when city officials informed residents of the public housing complex that EPA samples taken in 2014 and 2015 showed the ground was “highly contaminated” with lead and arsenic. The lead level was as high as 91,000 parts per million, more than 200 times the federal safety threshold for areas where young children play. Officials told the 1,100 residents they had to leave the complex, which the city had built decades earlier on top of a former Anaconda Lead Products smelter.

Two years later, East Chicago residents like Lopez are still living with the consequences of this contamination, even as the Trump/Pence administration guts the regulatory framework that is supposed to protect people like them who live in the path of polluting industries. People of color disproportionately suffer from this pollution, in part because of decades of discriminatory housing policies. Mike Pence, who was governor of Indiana when the crisis in East Chicago broke, has helped set the tone for the administration’s posture toward these communities. His pattern of opposing environmental rules in favor of corporate polluters has been a defining, if overlooked, aspect of Pence’s career.

As speculation grows about the possibility he could become president, it’s worth examining Pence’s role in the decades-long neglect of East Chicago.

“I Wouldn’t Feel Any Safer With Him Being President”

On the day Donald Trump chose him as running mate, then-Gov. Pence’s administration received an update from the EPA expressing the agency’s increasing concern about the lead contamination in East Chicago, according to internal records obtained by Rolling Stone.

A subsequent email obtained by Rewire.News shows the extent to which the state, under Pence, considered East Chicago to be the federal agency’s responsibility.

“Thank you for continuing to keep us informed about the EPA work being performed at the East Chicago Superfund site,” Peggy Dorsey, a deputy assistant commissioner at IDEM, wrote to EPA officials on August 12, 2016. Pence was between campaign stops in Wisconsin and his hometown of Columbus, Indiana, where he declared that his top priority remained serving the people of his home state.

Dorsey wrote that the state was “monitoring recent developments in the community,” and offered to provide EPA with “any additional information that may assist you as the lead agency.” (In a statement to Rewire.News, IDEM said “EPA is in control of” Superfund sites and IDEM “only plays a supporting role.”)

Twelve days later, Pence flew back from North Carolina after tornadoes damaged mostly white Kokomo, Indiana. As the crisis in East Chicago spiraled into the national spotlight, he never visited the city.

In December 2016, just after the election, East Chicago Mayor Anthony Copeland pleaded with Pence to declare a state of emergency, which Copeland said would provide state resources that were “necessary to cope with the disaster.”

“We understand the devastating effects of lead and arsenic poisoning on humans, and especially on children,” Copeland wrote. “By this letter, I am imploring you to take action.”

Pence refused. In a letter to Copeland, his office outlined the steps it had taken, including supplying $200,000 in funding, and called the declaration unnecessary “given the level of coordination among federal, state and local agencies.”

Pence’s successor, Republican Eric Holcomb, declared an emergency in East Chicago in February 2017, a month after he took office, ordering all state agencies to “continue developing and exploring ways to be of assistance in this matter.”

East Chicago residents like Akeeshea Daniels, who has suffered from myriad health problems and had to scramble to find housing when the city evacuated the complex, still have not forgotten Pence’s absence.

“I felt like when he could have done something, he didn’t do it. And it’s sad,” Daniels said. “I wouldn’t feel any safer with him being president.”

Government Run by the Koch Brothers

Since taking office, the Trump/Pence administration has moved to roll back at least 76 environmental rules, including resolving to overlook the impact of the most toxic chemicals on water, air, and soil; tried to cut the EPA’s budget by a quarter; placed a former chemical industry trade group executive in charge of helping to oversee the EPA’s chemical unit; tried to shutter the agency that investigates chemical plant disasters; and nominated a former Dow Chemical attorney to lead the Superfund program. Dow merged last year with DuPont, which ran a plant in East Chicago, a site contaminated with lead and arsenic.

Most recently, the administration acknowledged that its plans to rescind regulations on coal-burning power plants would cause up to 1,400 premature deaths annually, the New York Times reported.

The administration’s road map to deregulation is reportedly based on a wish list developed by Freedom Partners, funded by the billionaire Koch brothers. Pence has formed a key bridge between corporate donors like the Kochs and Trump.

“If Pence were to become president for any reason, the government would be run by the Koch brothers—period,” Democratic Rhode Island Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse told The New Yorker’s Jane Mayer. “He’s been their tool for years.”

Before he resigned in a tangle of scandal, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt added the East Chicago Superfund site to a list of areas with “the greatest expected redevelopment and commercial potential.” Advocates worried his goal was to make the sites available as soon as possible for industries to pollute again. Recommendations from the EPA’s Superfund Task Force refer prominently to corporate “reuse” of polluted sites. Pruitt’s replacement, Andrew Wheeler, is a former coal industry lobbyist.

Despite these changes, the EPA said in a statement to Rewire.News that it “has set an aggressive cleanup timeline” for Zones 2 and 3 of the East Chicago Superfund site, cleaning 430 yards there since 2016, as well as the interiors of nearly 400 homes across all three zones.

Residents like Lopez say this is far from enough.

“Would You Live Here?”

Since she was six months old, Lopez has lived near the site where DuPont manufactured lead arsenate insecticide until 1949.

Lead is known mostly for the damage it can do to children, including cognitive impairments that may last a lifetime. But it has been linked to a host of other conditions, including bone density loss. In Flint, Michigan, where an unelected emergency manager switched the city’s water source to the corrosive Flint River to save money, the subsequent lead contamination led to a “horrifyingly large” increase in miscarriages. East Chicago, for its part, has an infant mortality rate of 16.3 per 1,000 births, more than double the state rate.

It’s difficult to draw a firm line between a person’s health history and the contamination, in part because blood testing is an incomplete indicator of long-term exposure, and because the combined effects of heavy metals like the ones in East Chicago are not well understood.

Lopez and Daniels both underwent hysterectomies after suffering from hemorrhaging that they believe was linked to the contamination. Lopez was devastated by the procedure. She had always wanted kids. Now she lives with her three dogs: her “four-legged children.” Despite being sick for much of her life, at 55 she has outlived her entire immediate family.

Her brother collapsed on her porch while replacing a lightbulb and died at the age of 44. Her sister suffered from diabetes and a series of strokes, and died at the age of 42. Another brother died young from an unrelated accident. Her mother died from cancer that spread to her liver, which Lopez said was ravaged by cirrhosis, even though her mother rarely drank. Her father collapsed at the dining room table and died from a cardiovascular aneurysm at the age of 60. Arsenic and lead have been linked to liver cancer and cardiovascular problems, respectively.

“This is me as Maritza, this is my pain, my suffering right now,” Lopez said, crying, in her living room last spring. Earlier in the day, during a meeting with residents and EPA representatives, Lopez had been composed and authoritative.

“That is Business Maritza. I can’t let my personal come out. Because then I’m not going to be of no help to nobody,” she said.

“This is where I do my screaming—by myself.”

Last year, the EPA dug up and carted away parts of Lopez’s yard and cleaned the inside of her home to remove contaminated dust. But when it rains heavily or when the snow melts in winter, groundwater seeps into her basement, bringing whatever contaminants may still be nestled further down in her soil. In a letter to the EPA in April this year, Lopez, Daniels, and other residents outlined flaws with the cleaning, including the fact that the agency was using different measurement units for the test results they gave residents before and after the indoor cleanups, making it difficult to tell if they had an impact. (In its response, the EPA said the pre- and post-cleaning numbers are “fundamentally different” and “not meant to be compared.”) The city is supposed to replace Lopez’s lead water-service pipes, but this process, too, has stalled.

To this day, many residents still don’t feel as if they have an answer to a question East Chicago resident Jackie Brown put to the EPA representatives at the April 2017 meeting.

“I think one question that would answer everything is: ‘Would you live here?’” Brown asked. “Would you live in a house that’s been excavated and remediated?”

The workers didn’t say.

“Everybody Dropped the Ball”

The school year has just started, but Akeeshea Daniels has already received calls from her son Xavier’s school about how her eighth-grader isn’t following instructions. Daniels moved with Xavier to the West Calumet public housing complex when he was about a month old. She fears she might have to go sit in the back of her son’s classroom to keep him on task—something she has done before to help manage his ADHD. Now that he is 14 and six-foot-one, she worries that if he misbehaves, his teachers will see her son as a threat. Daniels blames the lead, which has been shown to cause attention problems in children.

After residents learned about the lead levels, attorneys last year helped Daniels obtain her son’s medical records, which appear to show he had blood lead levels high enough to recommend action under current CDC recommendations when he was 1, 3, and 4 years old. Daniels said no one told her about the results, and it’s unclear if they were ordered by a government agency. In 2016, EPA tests found 32,000 parts per million of lead in her home at the complex, more than 100 times the federal safety limit.

“Everybody dropped the ball, to me, every agency dropped the ball and could have done more,” Daniels, who is Black, told Rewire.News. “I’m to the point where I feel like, if we were a different color, things would have been done faster.”

After the city evicted her from the housing complex, Daniels stayed in East Chicago, where her grandmother lives. She moved to Zone 3 of the Superfund site, where she remains in the path of industry, with a Marathon gas pipeline right by her house. The city housing authority was supposed to test her new home for lead risks before she moved in, but more than a year later, she said they still haven’t. Asked about this failure, the housing authority referred Rewire.News to an attorney who did not respond to calls. And no one has answered Daniels’ questions about the long-term consequences of lead and arsenic.

Instead, she’s been left to wonder to what extent the contaminants are to blame for her family’s health problems: her rheumatoid arthritis, hypertension, and kidney stones, and the loss of 50 percent of her bone mass; Xavier’s asthma and many allergies; her son Diamante’s scoliosis, kidney stones, and digestive problems; and her sons’ bouts with scarlet fever. At 29, Daniels went through menopause after her hysterectomy. At 42, her teeth are brittle and loose enough to move with her tongue, but she lacks dental coverage. She wants a clinic in East Chicago that specializes in treating people exposed to heavy metals. Residents have also called for universal health coverage for everyone at the Superfund site. But as the months go by, Daniels has seen little progress.

“A lot of people have forgotten about us, I believe,” Daniels told Rewire.News in May, before Scott Pruitt’s resignation. “With so much going on in D.C., with Mr. Pruitt and different people, they forgot about the people.”

About 2,000 people still live at the East Chicago Superfund site. Many are too elderly, sick, or poor to leave. Maritza Lopez, for example, makes just enough from her fixed income and her late mother’s pension to afford her $600 monthly mortgage payment and basic needs.

Recently, Lopez began losing weight so rapidly, doctors were afraid she wouldn’t survive if they couldn’t determine a cause. In August, she was down to about 83 pounds—68, the doctors say, without her excess skin. But on many Saturdays, she still goes to meetings about the Superfund site.

“My fight is: I can’t allow another child to end up like me,” Lopez told Rewire.News, her voice breaking slightly. “[Or] another adult who most likely is probably feeling the beginning of symptoms. I want them to have the health care, to get the testing, the appropriate testing, and get analyzed and get treated before they end up like me. So if they have children they don’t lose their parents like I lost mine, or their family members or their siblings like I lost mine.”

“That is my fight.”

Jenn Stanley contributed to this report.