Sessions’ Weed Adviser Wants to Drug Test Everyone. Yes, Everyone.

This is par for the course in Robert DuPont's decades-long battle against cannabis—and with Attorney General Jeff Sessions at the helm of the Department of Justice, he's found a kindred spirit in his cause.

You’ve likely heard the term “gateway drug,” or the notion that smoking weed will lead to doing harder drugs like cocaine, heroin, and meth. In his 1987 hit song “Sign o’ the Times,” Prince refers to cannabis as a gateway drug to heroin: “In September, my cousin tried reefer for the very first time; now he’s doing horse—it’s June.”

You may have also heard that the term “gateway drug” turned out to be a myth. (Sorry, Prince’s cousin.)

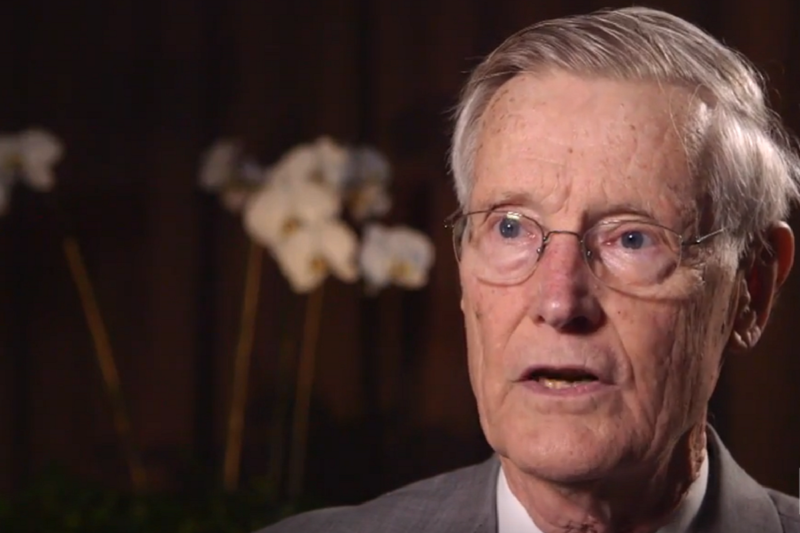

But you may not have heard of Robert DuPont, who popularized the term in the 1980s. Today, the 81-year-old is continuing to wage his war against cannabis as policy adviser to Attorney General Jeff Sessions. And he’s not stopping at physical possession. If DuPont gets his way, internal possession of narcotics will be against the law, and drug testing could become a routine part of your visit to the doctor.

This would be drug testing gone wild, and a likely violation of the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment. It’s par for the course, however, in DuPont’s decades-long battle against cannabis—and with Sessions at the helm of the Department of Justice, he’s found a kindred spirit in his cause.

DuPont “began his career as a liberal on drug control in the 1970s,” as Christopher Moraff reported for the Daily Beast. He launched the first methadone clinic in Washington, D.C., in 1971 to provide treatment for people addicted to heroin and advocated for the decriminalization of cannabis.

But by 1978, after having served as Nixon’s drug czar and the first director of the National Institute on Drug Addiction (NIDA), he switched sides in the “War on Drugs.” After a four-year stint at NIDA, he ventured into the drug-testing technology industry. It ultimately became financially beneficial to oppose the legalization of cannabis and to advocate for widespread drug testing, which often used technology in which he had a financial interest, Moraff reported. (For his part, DuPont denies any financial interest—sort of: “I just think, there is a financial incentive in drug testing, but the reason I’m interested in drug testing is that there is an interest from the disease standpoint.”)

By the 1980s, DuPont was staunchly opposed to cannabis legalization. And in 1991, while he was running a drug-testing firm that he co-founded with a former head of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), DuPont advocated for drug testing welfare recipients in a policy document that the Heritage Foundation published, according to the Daily Beast.

To give you a taste of how radical his views on drug control became, DuPont advocated testing “not only the adults on public assistance, but also their children.”

In 2010, DuPont helped draft a model bill that was supposed to provide law enforcement tools to deal with drugged driving. But in reality, the law goes much farther than that.

The bill would permit law enforcement who suspect a person of driving under the influence to test the driver not just for alcohol blood level, but for all controlled substances. The bill exempts drivers who consumed controlled substances through a prescription from their doctor, but it explicitly does not apply to medical cannabis users.

More ominously, however, the bill includes a section entitled “prohibiting the internal possession of chemical or controlled substances.”

Internal possession (as opposed to physical possession) means that the drugs are in your system and not, for example, in your pocket: “Any person who provides a bodily fluid sample containing any amount of a chemical or controlled substance … commits an offense punishable in the same manner as if the person otherwise possessed that substance,” the section reads.

The bill goes on to note that the section is not limited to traffic stops and DUIs. It applies to “any person who tests positive for chemical or controlled substances.”

So what does this all mean?

It means that anytime you give blood, it can be tested for narcotics and you could be subject to federal criminal charges.

DuPont wants drug screens to be routine in all practices of medicine, according to the Daily Beast’s interview with him. He thinks the health-care industry should “approach addiction in the same way as diabetes, and that includes monitoring.” He also wants to give doctors the authority to force patients into substance use disorder treatment against their will.

If that sound authoritarian, paternalistic, and like a gross invasion of privacy, that’s because it is. But that’s the world DuPont wants.

“Doctors already check for things like cholesterol and blood sugar, why not test for illicit drugs?” DuPont remarked in the interview.

The constitutional answer to DuPont’s question is that the Fourth Amendment precludes it.

The Fourth Amendment says, “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

That right—like so many constitutional rights—is not absolute. In emergency cases, courts will permit law enforcement to conduct searches and seizures without a warrant and without probable cause.

But what DuPont is advocating is radical: mandatory drug testing and involuntary detention. And the U.S. Supreme Court has already chimed in.

In Skinner v. Railway Labor Executives’ Association, the Court ruled that drug testing is a Fourth Amendment search but that “special needs” beyond ordinary law enforcement might justify a departure from the usual probable cause and warrant requirements. This is known as the “special needs doctrine” and it permits, in emergency cases, law enforcement to conduct searches and seizures without a warrant and without probable cause.

Generally, such emergency cases must be in the interest of protecting public safety.

In Skinner, that’s exactly why the Court ruled in favor of the employer. It said that public safety was paramount and ruled that the Railway was well within its rights to drug test its employees. The minimal intrusion on privacy was justified by the government’s need to combat what it saw as an overriding public danger—trains being driven by drunk and high people.

In National Treasury Employees Union v. Von Raab, which was handed down on the same day as Skinner, the Court permitted the suspicionless drug testing of U.S. Customs Service employees who wanted to be transferred or promoted to certain sensitive positions: “We hold that the suspicionless testing of employees who apply for promotion to positions directly involving the interdiction of illegal drugs, or to positions that require the incumbent to carry a firearm, is reasonable.”

And in Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls and Vernonia School District 47J v. Acton, the Court ruled that drug testing of high school students who were athletes or otherwise participated in extracurricular activities did not run afoul of the Fourth Amendment, partly because minors have a diminished expectation of privacy as compared to adults.

So the question is: In light of this Supreme Court precedent, is requiring doctors—or phlebotomists, or anyone else taking fluid samples—to drug test their patients and potentially force them into rehab against their will a violation of their patients’ Fourth Amendment’s rights?

You’d be hard pressed to argue that it isn’t.

The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals tackled in 2014 a similar issue in Lebron v. Secretary of the Florida Department of Children and Families. In that case, Luis Lebron—an applicant seeking Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits—challenged a Florida statute that required suspicionless drug testing of all TANF applicants.

Florida countered by citing the special needs doctrine. It argued that TANF applicants were at a special risk for drug addiction.

The 11th Circuit rejected Florida’s claims. Florida didn’t offer evidence that TANF applicants were different from drug users in the general population, so the special needs doctrine didn’t apply. Besides, the court pointed out that Florida’s interest in ensuring that TANF applicants weren’t drug users did not compare to the “narrow category of special needs that justify blanket drug testing of railroad workers, certain federal Customs employees involved in drug interdiction or who carry firearms, or students who participated in extracurricular activities because those programs involve ‘surpassing safety interests’.”

It is unlikely that DuPont’s vision will ever come to pass. If such a thing were to happen, the constitutional hurdles alone would take years to navigate in court. And all the constitutional logic aside, there’s also the common-sense answer to DuPont’s question of “why not”: It cannot possibly be reasonable to require mandatory, suspicionless drug testing of everyone who seeks medical care.

There is a difference between agreeing to drug testing in a school or employee context. If you don’t want to be subjected to the test, don’t take up field hockey or apply for that job driving trains. But that logic doesn’t apply when it comes to doctors forcing you to undergo drug testing. If you have a problem with addiction, the choice between obtaining health care that requires blood or urine samples and risking involuntary treatment or incarceration, and remaining sick, is not really a choice at all.

And let’s be honest: We all know who these laws would target. If there’s one thing Sessions—who met with DuPont in a closed-door December meeting, as the Daily Beast reported, “to discuss federal options for dealing with the rapid liberalization of state marijuana laws”—appears to abhor more than Black people, it’s weed. Also, studies have linked poverty and social conditions to drug addiction, so forcing patients to assent to drug tests will likely lead to fewer impoverished people seeking medical care.

But perhaps that is the point: to keep poor people—who likely don’t have broad access to health care in the first place—from daring to seek treatment at an emergency room when they have a crisis.

After all, it wasn’t too long ago that a newly minted Republican congressman named Roger Marshall who spent 30 years as a physician before packing up his medical kit and heading to Washington said that poor people “just don’t want health care and aren’t going to take care of themselves.”

If that is the prevailing view of poor people’s relationship to the health-care system, then why not use mandatory drug testing to weed out the people who “deserve” health care from those who don’t?

At least it’ll save poor people money so they can buy iPhones.