The Supreme Court’s Racial Gerrymandering Order in North Carolina Is Not Necessarily Good News

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous and unsigned opinion, affirmed the lower court's determination that the redistricting was an illegal gerrymander, but it vacated the lower court’s order mandating a special election.

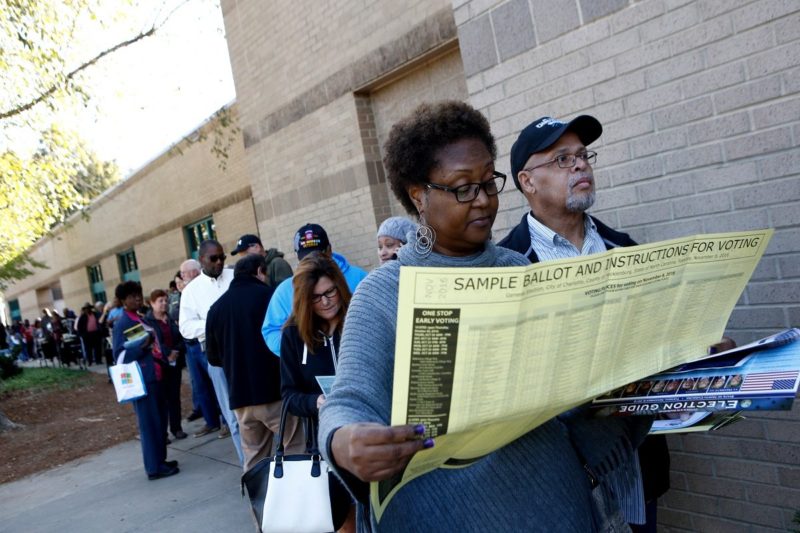

In a brief order this morning, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed a lower court ruling striking down North Carolina redistricting efforts as unconstitutional racial gerrymandering that disproportionately affected Black voters.

While this is a definite win for Black voters in North Carolina, the Court’s order won’t serve as a much-needed deterrent for racial gerrymandering efforts around the country.

In 2015, in a case called North Carolina v. Covington, 31 North Carolina residents sued elections officials and the state, challenging legislative redistricting efforts. The plaintiffs claimed that when Republicans redrew districting maps in 2011, they packed Black voters into nine senate districts (out of 50) and 19 house districts (out of 120) in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

After trial, the lower court agreed that the 28 majority Black districts were unconstitutional racial gerrymanders. But the court didn’t simply rule that the redistricting efforts were illegal; the court also ordered the North Carolina General Assembly to draw remedial maps by March 2017 and to hold a special fall 2017 election using the new districts. The court limited the terms of legislators elected in 2016 to one year instead of two in order to accommodate the special election, according to the Supreme Court’s order.

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous and unsigned opinion, affirmed the lower court’s determination that the redistricting was an illegal gerrymander, but it vacated the lower court’s order mandating a special election.

“Relief in redistricting cases is fashioned in the light of well-known principles of equity. A district court therefore must undertake an ‘equitable weighing process’ to select a fitting remedy for the legal violations it has identified, taking account of ‘what is necessary, what is fair, and what is workable,’” the Supreme Court said.

This “equitable weighing process” in order to remedy the effects of the gerrymandering is known in legalese as “balancing the equities.”

“Although this Court has never addressed whether or when a special election may be a proper remedy for a racial gerrymander,” the Court continued, “obvious considerations include the severity and nature of the particular constitutional violation, the extent of the likely disruption to the ordinary processes of governance if early elections are imposed, and the need to act with proper judicial restraint when intruding on state sovereignty.”

Because the lower court balanced the equities in what the Supreme Court determined was a cursory fashion, it instructed the lower court to reweigh the balance of the equities in order to determine whether or not a special election in 2017 is appropriate.

While the Supreme Court order sounds like good news for voting rights advocates who want to see Republican racial gerrymandering efforts dismantled, the Court’s opinion may actually encourage more racial gerrymandering in the future.

As Ian Millhiser points out at ThinkProgress, the legislature drew the maps in 2011. The lower court opinion decrying the maps as illegal and ordering a special election was issued in 2016, and it was 2017 before the Supreme Court affirmed that order. During that time period, North Carolina held three elections using illegal maps.

Had the Supreme Court permitted the special election in North Carolina that the lower court ordered to go forward, the time period North Carolinians would have been governed by legislators elected using illegal maps would have been reduced by a year. And lawmakers might hesitate before engaging in racial gerrymandering out of fear of having to run special elections that might undo the gains obtained using illegal maps.

But the Court’s order requiring North Carolina to do more than a cursory balancing of the equities to determine to whether a special election was appropriate signals, as Millhiser points out, that the justices were irritated by the lower court’s decision ordering a special election.

So what we’re left with is an order that decries racial gerrymandering, but also side-eyes special elections as a remedy for that gerrymandering, with no specific suggestions as to an appropriate remedy instead.

As Millhiser aptly put it:

Whether the justices intended it to or not, however, Covington will also send a clear message to lawmakers engaged in gerrymandering. North Carolina’s maps are illegal. The Supreme Court agreed with that conclusion. And yet North Carolina still got to run several elections under those maps.

Had the Court left alone the lower court’s decision mandating a special election, the threat of wasting taxpayer funds and time on special elections would hang like the Sword of Damocles over the heads of lawmakers keen on redrawing maps to disadvantage Black voters.

Unfortunately, the slow pace of litigation and the Court’s reticence regarding remedial special elections means that this can be a signal: Lawmakers can freely engage in racial gerrymandering in the hopes that at least a few elections can be run using illegal maps before being struck down as unconstitutional, and that even when those maps are struck down, those elected under those illegal maps might still be able to serve out their full terms.

Republican lawmakers have little to lose and everything to gain. And voters, of course, lose as well; politicians elected using illegal maps in heavily redistricted areas are unlikely to represent or prioritize the needs of the voters living in their districts.