Kansas Submits Brief Citing ‘Dred Scott’ in Effort to Ban Abortion, Then Withdraws It

There was no legitimate reason to cite the landmark 1857 U.S. Supreme Court decision that said Black Americans had no citizen rights. Including the case in a modern-day legal battle is just Kansas officials being terrible in their ongoing quest to deprive women of their autonomy.

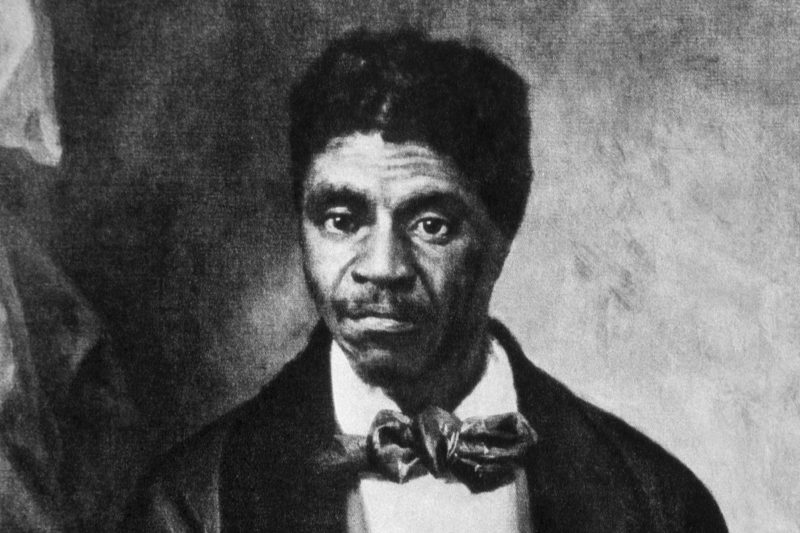

Dred Scott v. Sandford, the 1857 case that held persons of “African descent” could not become United States citizens, is widely regarded as being one of the worst—if not the worst—U.S. Supreme Court decision in history.

In that case, pro-slavery Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, writing for the majority, ruled that Dred Scott could not sue for his freedom, and the freedom of his wife and daughter, because he was not a citizen and therefore had no standing to sue in federal court.

It was an abomination of a decision. So why the hell did Kansas Solicitor General Stephen McAllister cite it approvingly in a brief submitted to the Kansas Supreme Court in defense of SB 95, a law that would effectively ban abortion after 14 weeks?

I don’t know the answer to that question, and believe me, I’ve tried to figure it out. When I asked my colleague, Rewire Vice President of Law and the Courts Jessica Mason Pieklo, why she thought Kansas officials had done so, she responded, “Because they’re being terrible.” (She actually didn’t say “terrible,” but what she did say is too, shall we say, intemperate for publication.)

That’s as good a reason as ever, given the context in which McAllister cited the case, and given that the same day he submitted the brief, Kansas Attorney General Derek Schmidt withdrew the submission, apologizing for including the offensive citation.

But let’s back up a bit and go over what this lawsuit is all about.

In 2015, Gov. Sam Brownback (R) signed into law a piece of legislation known as the “Unborn Child Protection from Dismemberment Abortion Act.” That’s anti-choicer speak for a law banning a procedure known as “dilation and evacuation,” which is commonly used to terminate second–trimester pregnancies.

Last June, the Center of Reproductive Rights filed a lawsuit on behalf of two abortion providers challenging the law as unconstitutional. They allege that SB 95 violates a person’s fundamental right to an abortion under Sections 1 and 2 of the Kansas Constitution Bill of Rights.

Those sections “provide broad protection to the liberty interest of Kansas citizens and have never been interpreted by the Kansas appellate courts to provide less protection than the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution,” according to the brief plaintiffs submitted to the Kansas Supreme Court.

In an amicus brief they submitted for the Kansas Supreme Court’s consideration in support of the plaintiffs, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Constitutional Accountability Center (CAC) note that the 14th Amendment, like Section 1 of the Kansas Constitution’s Bill of Rights, draws directly from the Declaration of Independence and its lofty language about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Both Section 1 of the Kansas Constitution’s Bill of Rights and Section 1 of the 14th Amendment “share a common design: both were written to incorporate the principles of liberty and equality set forth in the Declaration of Independence and thereby guarantee broad protection of substantive fundamental rights,” argued the ACLU and CAC. One of the key components of the 14th Amendment is the due process clause, which birthed unenumerated personal liberty rights (known in legal circles as “substantive due process rights”), such as the right to an abortion and to use contraception.

The right to an abortion is one such substantive fundamental right, as is the right to marry someone of another race, the right to shag someone of the same sex in the privacy of your own home, and the right to use contraception. These rights aren’t enumerated in the U.S. Constitution, but courts—namely the Supreme Court—have nevertheless seen fit to protect them as fundamental to personal liberty.

Not so, according to the solicitor general.

Section 1 of the Kansas Constitution’s Bill of Rights and Section 1 of the 14th Amendment are “different provisions with different text adopted at different times in different circumstances and for different reasons,” according to the solicitor general’s brief.

The Kansas Constitution does not contain any substantive fundamental rights, according to Kansas. Indeed, the Kansas Constitution doesn’t even contain a due process clause. The men who ratified the Kansas Constitution in 1859 could have listed the right to an abortion in the text. And over the last hundred or so years, the people could have amended the Constitution to include the right to an abortion. But they didn’t, thus confirming, according to the solicitor general, that they did not intend for that right to be included.

Put simply, the solicitor general seems to believe that all rights afforded protection by the Kansas Constitution must be enumerated in the Kansas Constitution. That means, at least in theory, no contraception and no same-sex marriage, in addition to no abortion.

But that’s not what courts in Kansas have ruled.

As the Court of Appeals noted in its opinion siding with plaintiffs, “[t]he Kansas Supreme Court has consistently interpreted sections 1 and 2 of the Kansas Constitution Bill of Rights as equivalent to the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

And because the right to an abortion is a personal liberty protected by the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, “the Kansas Constitution provides the same right to abortion that is protected under federal law.”

It’s in that context that McAllister approvingly cited Dred Scott. In an attempt to bolster his claim that the Kansas Constitution’s talk of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—principles described in the Declaration of Independence—was merely a set of ideals and did not provide any substantive rights to Kansans, he included seven case citations. One of those citations was to Dred Scott which, the solicitor general writes, describes “the Declaration’s description of unalienable rights as merely ‘general words used in that memorable instrument’” and holds that “the Declaration did not have a legally binding effect.” In other words, he used Dred Scott to claim that kind of language was nothing more than fancy rhetoric.

As Mark Joseph Stern pointed out in Slate, “It was in this context that the Dred Scott court declared that the Declaration of Independence had no binding legal effect”:

The “language used in the Declaration of Independence,” Taney wrote, shows “that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument.” This passage is exactly what Kansas cites to prove that the declaration is merely a “memorable instrument” with no legal effect—a passage concluding that black people, “that unfortunate race,” could never become part of “the people” who receive full rights under the law.

To call it bizarre is an understatement.

As someone who has written more than her fair share of legal briefs, I can tell you this: You don’t often see approving citations in briefs to the Court’s worst decisions. I’m talking about cases like Plessy v. Ferguson, Bowers v. Hardwick, Buck v. Bell, and Korematsu v. United States. These are the cases that make almost everyone—liberals and conservatives alike—recoil in horror. And there’s virtually no legal principle that can be found in those cases that cannot be found in other less horrible cases. So why cite Dred Scott?

I can also tell you that you don’t need seven citations when six, or five, or even four will do. Lawyers, especially young lawyers, have a tendency to want to say “I’m right! And look at all these cases that make the same brilliant point that I just have!” That’s a practice that a good seasoned brief writer will beat out of you in order to transform you into a good brief writer. You don’t need that extra citation in order to prove your point. And you certainly don’t need that extra citation when you’re pointing to a case written by one of the most notorious racists to ever sit on the Court, Chief Roger B. Taney.

My point is this: There is absolutely no conceivable reason that Kansas officials included this citation in the brief. At least, there’s no good reason.

Perhaps my learned colleague Jessica Mason Pieklo is right: They included it to be terrible.

Fortunately, someone in Kansas, Attorney General Derek Schmidt, came to his senses and released a statement apologizing for citing Dred Scott:

Yesterday’s reference to Dred Scott in a State’s response brief does not accurately reflect the State’s position, is not necessary for the State’s legal argument, and should not have been made. Neither the State nor its attorneys believe or were arguing that Dred Scott was correctly decided. Nonetheless, the reference to that case was obviously inappropriate, and as soon as I became aware of it today, I ordered the State’s brief withdrawn. The unfortunate use of this citation should not distract from the important question the Kansas Supreme Court faces in this case: Whether the Kansas Constitution establishes a state-level right to abortion. The State will continue to argue vigorously that it does not.

Schmidt submitted a request to the Kansas Supreme Court to withdraw the brief, which is a good thing. I mean, Kansas officials will obviously continue to try to strip women of their human rights—that’s what they do—but they don’t have to be so awful about it.