Justice Kennedy’s Silence Speaks Volumes About His Apparent Feelings on Women’s Autonomy

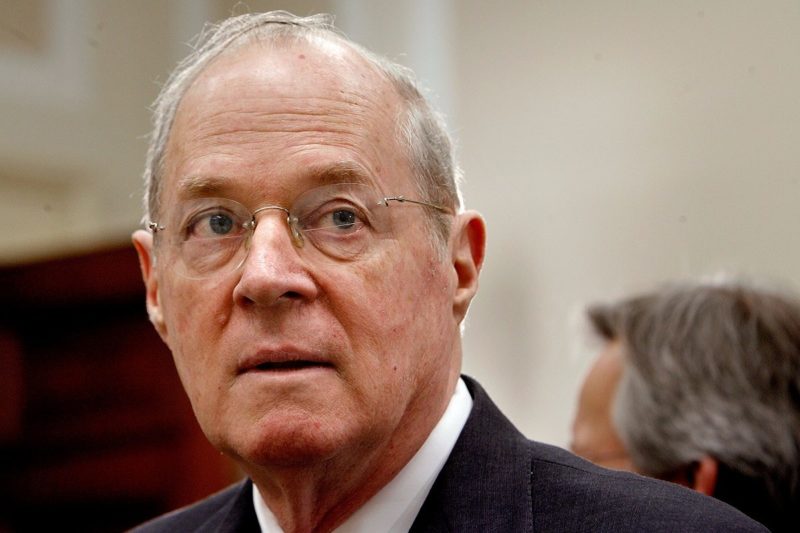

Justice Anthony Kennedy’s obsession with human dignity has become a hallmark of his jurisprudence—except where reproductive rights are concerned.

Last week’s decision in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt was remarkable not just for what it did say—that two provisions in Texas’s omnibus anti-abortion law were unconstitutional—but for what it didn’t say, and who didn’t say it.

In the lead-up to the decision, many court watchers were deeply concerned that Justice Anthony Kennedy would side with the conservative wing of the court, and that his word about targeted restrictions of abortion providers would signal the death knell of reproductive rights. Although Kennedy came down on the winning side, his notable silence on the “dignity” of those affected by the law still speaks volumes about his apparent feelings on women’s autonomy. That’s because Kennedy’s obsession with human dignity, and where along the fault line of that human dignity various rights fall, has become a hallmark of his jurisprudence—except where reproductive rights are concerned.

His opinion on marriage equality in Obergefell v. Hodges, along with his prior opinions striking down sodomy laws in Lawrence v. Texas and the Defense of Marriage Act in United States v. Windsor, assured us that he recognizes the fundamental human rights and dignity of LGBTQ persons.

On the other hand, as my colleague Jessica Mason Pieklo noted, his concern in Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action about the dignity of the state, specifically the ballot initiative process, assured us that he is willing to sweep aside the dignity of those affected by Michigan’s affirmative action ban in favor of the “‘dignity’ of a ballot process steeped in racism.”

Meanwhile, in his majority opinion in June’s Fisher v. University of Texas, Kennedy upheld the constitutionality of the University of Texas’ affirmative action program, noting that it remained a challenge to this country’s education system “to reconcile the pursuit of diversity with the constitutional promise of equal treatment and dignity.”

It is apparent that where Kennedy is concerned, dignity is the alpha and the omega. But when it came to one of the most important reproductive rights cases in decades, he was silent.

This is not entirely surprising: For Kennedy, the dignity granted to pregnant women, as evidenced by his opinions in Planned Parenthood v. Casey and Gonzales v. Carhart, has been steeped in gender-normative claptrap about abortion being a unique choice that has grave consequences for women, abortion providers’ souls, and the dignity of the fetus. And in Whole Woman’s Health, when Kennedy was given another chance to demonstrate to us that he does recognize the dignity of women as women, he froze.

He didn’t write the majority opinion. He didn’t write a concurring opinion. He permitted Justice Stephen Breyer to base the most important articulation of abortion rights in decades on data. There was not so much as a callback to Kennedy’s flowery articulation of dignity in Casey, where he wrote that “personal decisions relating to marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, child rearing, and education” are matters “involving the most intimate and personal choices a person may make in a lifetime, choices central to personal dignity and autonomy.” (While Casey was a plurality opinion, various Court historians have pointed out that Kennedy himself wrote the above-quoted language.)

Of course, that dignity outlined in Casey is grounded in gender paternalism: Abortion, Kennedy continued, “is an act fraught with consequences for others: for the woman who must live with the implications of her decision; for the persons who perform and assist in the procedures for the spouse, family, and society which must confront the knowledge that these procedures exist, procedures some deem nothing short of an act of violence against innocent human life; and, depending on one’s beliefs, for the life or potential life that is aborted.” Later, in Gonzales, Kennedy said that the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban “expresses respect for the dignity of human life,” with nothing about the dignity of the women affected by the ban.

And this time around, Kennedy’s silence in Whole Woman’s Health may have had to do with the facts of the case: Texas claimed that the provisions advanced public health and safety, and Whole Woman’s Health’s attorneys set about proving that claim to be false. Whole Woman’s Health was the sort of data-driven decision that did not strictly need excessive language about personal dignity and autonomy. As Breyer wrote, it was a simple matter of Texas advancing a reason for passing the restrictions without offering any proof: “We have found nothing in Texas’ record evidence that shows that, compared to prior law, the new law advanced Texas’ legitimate interest in protecting women’s health.”

In Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s two-page concurrence, she succinctly put it, “Many medical procedures, including childbirth, are far more dangerous to patients, yet are not subject to ambulatory-surgical-center or hospital admitting-privileges requirements.”

“Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers laws like H.B. 2 that ‘do little or nothing for health, but rather strew impediments to abortion,’ cannot survive judicial inspection,” she continued, hammering the point home.

So by silently signing on to the majority opinion, Kennedy may simply have been expressing that he wasn’t going to fall for the State of Texas’ efforts to undermine Casey’s undue burden standard through a mixture of half-truths about advancing public health and weak evidence supporting that claim.

Still, Kennedy had a perfect opportunity to complete the circle on his dignity jurisprudence and take it to its logical conclusion: that women, like everyone else, are individuals worthy of their own autonomy and rights. But he didn’t—whether due to his Catholic faith, a deep aversion to abortion in general, or because, as David S. Cohen aptly put it, “[i]n Justice Kennedy’s gendered world, a woman needs … state protection because a true mother—an ideal mother—would not kill her child.”

As I wrote last year in the wake of Kennedy’s majority opinion in Obergefell, “according to [Kennedy’s] perverse simulacrum of dignity, abortion rights usurp the dignity of motherhood (which is the only dignity that matters when it comes to women) insofar as it prevents women from fulfilling their rightful roles as mothers and caregivers. Women have an innate need to nurture, so the argument goes, and abortion undermines that right.”

This version of dignity fits neatly into Kennedy’s “gendered world.” But falls short when compared to jurists internationally, who have pointed out that dignity plays a central role in reproductive rights jurisprudence.

In Casey itself, for example, retired Justice John Paul Stevens—who, perhaps not coincidentally, attended the announcement of the Whole Woman’s Health decision at the Supreme Court—wrote that whether or not to terminate a pregnancy is a “matter of conscience,” and that “[t]he authority to make such traumatic and yet empowering decisions is an element of basic human dignity.”

And in a 1988 landmark decision from the Supreme Court of Canada, Justice Bertha Wilson indicated in her concurring opinion that “respect for human dignity” was key to the discussion of access to abortion because “the right to make fundamental personal decision without interference from the state” was central to human dignity and any reading of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982, which is essentially Canada’s Bill of Rights.

The case was R. v. Morgentaler, in which the Supreme Court of Canada found that a provision in the criminal code that required abortions to be performed only at an accredited hospital with the proper certification of approval from the hospital’s therapeutic abortion committee violated the Canadian Constitution. (Therapeutic abortion committees were almost always comprised of men who would decide whether an abortion fit within the exception to the criminal offense of performing an abortion.)

In other countries, too, “human dignity” has been a key component in discussion about abortion rights. The German Federal Constitutional Court explicitly recognized that access to abortion was required by “the human dignity of the pregnant woman, her… right to life and physical integrity, and her right of personality.” The Supreme Court of Brazil relied on the notion of human dignity to explain that requiring a person to carry an anencephalic fetus to term caused “violence to human dignity.” The Colombian Constitutional Court relied upon concerns about human dignity to strike down abortion prohibition in instances where the pregnancy is the result of rape, involves a nonviable fetus, or a threat to the woman’s life or health.

Certainly, abortion rights are still severely restricted in some of the above-mentioned countries, and elsewhere throughout the world. Nevertheless, there is strong national and international precedent for locating abortion rights in the square of human dignity.

And where else would they be located? If dignity is all about permitting people to make decisions of fundamental personal importance, and it turns out, as it did with Texas, that politicians have thrown “women’s health and safety” smoke pellets to obscure the true purpose of laws like HB 2—to ban abortion entirely—where’s the dignity in that?

Perhaps I’m being too grumpy. Perhaps I should just take the win—and it is an important win that will shape abortion rights for a generation—and shut my trap. But I want more from Kennedy. I want him to demonstrate that he’s not a hopelessly patriarchal figure who has icky feelings when it comes to abortion. I want him to recognize that some women have abortions and it’s not the worst decision they’ve ever made or the worst thing that ever happened to him. I want him to recognize that women are people who deserve dignity irrespective of their choices regarding whether and when to become a mother. And, ultimately, I want him to write about a woman’s right to choose using the same flowery language that he uses to discuss LGBTQ rights and the dignity of LGBTQ people. He could have done so here.

Forcing the closure of clinics based on empty promises of advancing public health is an affront to the basic dignity of women. Not only do such lies—and they are lies, as evidenced by the myriad anti-choice Texan politicians who have come right out and said that passing HB 2 was about closing clinics and making abortion inaccessible—operate to deprive women of the dignity to choose whether to carry a pregnancy to term, they also presume that the American public is too stupid to truly grasp what’s going on.

And that is quintessentially undignified.