The Next Supreme Court Justice Should Be Another Woman of Color

We need more justices with deeper roots in different communities and a broader worldview than white male candidates from Yale or Harvard, ones who are not devoted to the inevitable blind spots of a group of men who lived more than 200 years ago.

Read more of our articles on Justice Antonin Scalia’s potential successor here.

To fill the vacancy left on the Supreme Court by the death last weekend of Associate Justice Antonin Scalia, President Obama will nominate a new justice. That nominee should be a woman of color.

The thought that Obama will pick another justice has sent the GOP into a tizzy. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and others in the party are ignoring history and the Constitution to argue vehemently that Obama doesn’t have the authority to nominate anyone because it’s an election year. Instead, they say, that nomination should be left to the next president, a claim Obama has rightly swatted away.

This fight is, in reality, reflective of broad conservative efforts to hold onto a power structure set up two centuries ago by white males who didn’t just ignore, but had no concept of the rights of women or people of color. We need judges with broader perspectives, ones that are not unthinkingly devoted to a concept of America or of rights written by men who, no matter how otherwise brilliant, were not considering “all the people” when they wrote the Constitution.

The battle over this nomination is part of a longer-running struggle between the GOP and Obama. In January, long before Scalia died, the GOP-controlled Senate, egged on by the Heritage Institute, declared a blockade of sorts—a Senate work stoppage if you will—on confirmations of Obama’s judicial nominees. Under McConnell’s rein, the approval rate of federal judges has been slower than any period since 1969.

This political jockeying is also rooted in two long-running and intertwined debates about how the Constitution should be viewed and who gets to interpret it.

On one hand are the proponents of so-called originalism, the argument that the Constitution is a fixed document subject only to the most literal interpretation. On the other are those who see it as a living document, through which American jurisprudence, concerned as it must be with issues not previously foreseen and the rights of those not previously recognized, is built and sustained by the values on which the Constitution was based.

This is a false dichotomy that, I believe, hides a deeper struggle being waged by a white male establishment aligned with the wealthy and with corporate interests that, despite their collective power, are nonetheless threatened by rapidly changing demographics and a resurgence of collective organizing by progressive movements.

Originalists—often synonymous with conservatives—claim they want judges who won’t “legislate” from the bench. But all judges interpret the law; it’s what judges do. They have one job, and they inevitably bring with them their views of the law, its interpretation, and what came before it. What conservatives really want are judges who will decide cases favoring an outcome aligned with their own interpretation of a given issue, especially with regard to elevating corporate personhood, delegitimizing female personhood, and allowing restrictions on voting rights.

In fact, conservatives’ most revered hero, Justice Scalia, was among the most activist of activist justices. As Adam Cohen, a lawyer and former assistant editorial page editor of the New York Times, wrote in 2005:

The idea that liberal judges are advocates and partisans while judges like Justice Scalia are not is being touted everywhere these days, and it is pure myth. Justice Scalia has been more than willing to ignore the Constitution’s plain language, and he has a knack for coming out on the conservative side in cases with an ideological bent. The conservative partisans leading the war on activist judges are just as inconsistent: they like judicial activism just fine when it advances their own agendas.

Justices are not immune to bias either. We’ve already seen the most self-proclaimed “originalists” make up their own facts and use their own lenses through which to see and interpret the law. Scalia famously—but erroneously and shockingly—claimed that Black college students “couldn’t make it” in competitive universities. This was not based on fact, data, or personal experience; nor on an understanding of race, poverty, and the educational system. He likely arrived at his assertion through an amalgam of conservative talking points, internal bias, and intellectual laziness about the realities faced by people outside his circles and ideologies.

Similarly, Justice Anthony Kennedy either decided on his own, or is so taken with the mythology of the far right, that he wrote an opinion in a reproductive rights case proclaiming that most women have regrets about abortion, a statement that is not only right out of the anti-choice movement’s playbook, but has been widely refuted by scientific evidence.

So even while decrying “bias” and “empathy,” the right knows—and, indeed, depends on the fact—that judges’ thinking can be influenced by ideology and unproven claims. Otherwise, there would not be a years-long effort underway to influence Kennedy’s thinking on abortion leading up to cases like Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt.

The GOP is disgruntled not so much about literalists versus activists, but that a president they’ve worked for eight years to discredit gets to nominate another justice—one who is more likely than not to be someone the president feels will interpret the law fairly and with real people in mind. That’s why McConnell is holding up all the other appointments as well.

And that is the second part of the struggle underway: representation on the Court, and whether there is value, as Obama has asserted, in a judiciary that “looks like America.” Obama, and others, have argued that empathy and real-world experience are important qualifications in a judge, and that the courts should play a role as a “bastion of equality and justice for [all] U.S. citizens.” And while this administration waited far too long to begin nominating judges, to date, those nominated and confirmed have indeed made the judiciary look more “like America” than ever before.

In a 2014 New Yorker article, Jeffrey Toobin wrote:

Obama’s judicial nominees look different from their predecessors. In an interview in the Oval Office, the President told me, “I think there are some particular groups that historically have been underrepresented—like Latinos and Asian-Americans—that represent a larger and larger portion of the population. And so for them to be able to see folks in robes that look like them is going to be important. When I came into office, I think there was one openly gay judge who had been appointed. We’ve appointed ten.”

Toobin further noted that 42 percent of Obama’s judgeships have gone to women, compared with 22 percent of George W. Bush’s judges and 29 percent of Bill Clinton’s. Thirty-six percent of President Obama’s judges have been people of color, compared with 18 percent for Bush and 24 percent for Clinton.

This, I believe, is what the right most fears: Judges who represent a greater diversity of experiences and views, and who have roots in different communities, will interpret laws with a greater understanding of their effects on real people. And that would threaten the very foundation of the house that white men built, upon which the claims of originalism appear to be based.

History provides a sense of what is at stake. Well over 200 years ago, from May through September 1787, an esteemed group of men meeting in Philadelphia collaborated on writing the Constitution of the United States. The majority of the 55 men attending the Constitutional Convention became signatories to the document, and the thinking and writing of many others contributed to its development, some of whom, like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, are considered the Founding Fathers of this country.

Two years later, the U.S. Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789, thereby fulfilling Article III of the Constitution, which placed the judicial power of the new federal government in “one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts” as Congress deemed necessary. The first Supreme Court was composed of six justices, a number later expanded to nine justices to accommodate a growing federal judicial system.

Apart from their shared role in history and the fact they were men, the signatories to the Constitution also had other things in common: They were all white Protestants.

From the beginning, the Judiciary Act and the judiciary that resulted did indeed reflect a certain America: the one seen by the men in power. In laying out the roles and responsibilities of justices of the courts, the word “he” appears 23 times. This is no accident. The U.S. Constitution was written by white Protestant men for white Protestant men, albeit while recognizing the religious freedom of other white men.

These documents were written at a time when white men were still killing and taking over the lands of Native Americans, and when slavery was the foundation of the U.S. economy. At least some Founding Fathers were slave owners, and the notion of basic human rights for Black people or other persons of color simply did not exist.

Women were not counted as people either, at least not in any political sense. As wealthy white men wrote declarations and constitutions, their wives were meant to bear and raise the children of, run households for, and support any and all needs of their husbands and fathers. They could not vote, rarely owned property, and were dependent on men for status and income.

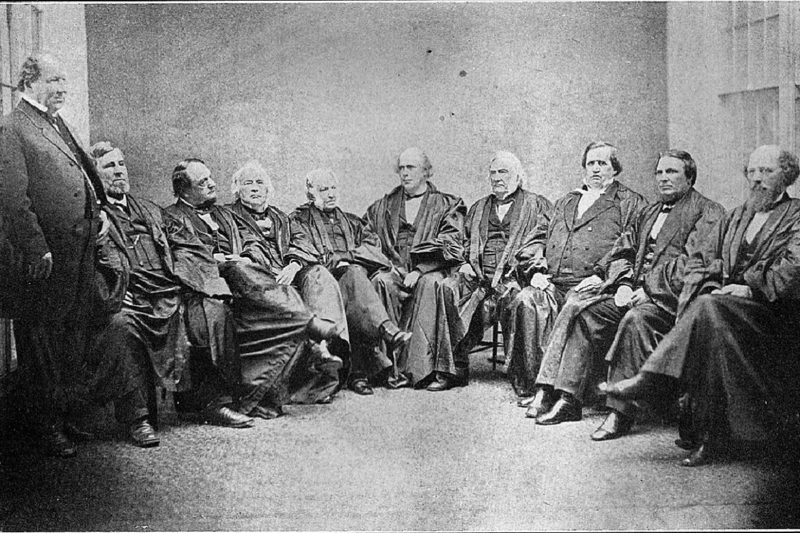

By and large, and until recently, this type of “originalism”—white Christian male as the normative standard—has remained largely unchallenged. The vast majority of justices have been white Christian males, predominantly Protestant with a few Catholics sprinkled in. As the slideshow below makes clear, that did not change even slightly for well over 100 years.

[slideshow_deploy id=’74112′]

The first Catholic justice, Roger B. Taney, was appointed in 1836. It took until 1916 before the Court had its first Jewish justice, Louis Brandeis, another 50 years to nominate Thurgood Marshall, the first Black Supreme Court justice, in 1967, and 14 more years from that to nominate Sandra Day O’Connor, the first female justice. The second Black justice, Clarence Thomas, was not nominated until 1991.

Today, nearly 51 percent of the U.S. population is female, a majority demographic. And the non-Hispanic white population, as traditionally defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, is an increasingly small share of the population. With the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, the Court is now comprised of four white men and one Black man, all of whom range in age from their early 60s to late 70s, and three women justices, two of whom are also white. Only four justices in 112 have been women.

The Supreme Court has therefore never been representative of the broader population of the country. In general, it has continued to represent the “original America” as seen by its authors—which, again, was itself never a true picture of the United States.

Given this history, it’s also fairly clear why there is a huge chasm between constitutional originalists and those who view the Constitution as a living document, one with consistent values that nonetheless have to be applied to new and different norms and questions. If you are a man or a person of wealth whose needs, rights, and economic interests fit comfortably under that original interpretation of law, you don’t need to reflect on the meanings or implications for other people of your judgments and decisions.

If, on the other hand, you recognize that there are historical injustices that were never even seen as injustices, and therefore never contemplated at the time of the writing of the Constitution, you probably believe some interpretation is necessary. If you thought a woman’s role was to bear children and be a homemaker, you didn’t need to protect or interpret her rights in a constitution. The freedoms, needs, aspirations, and rights of non-white, non-male persons simply were not considerations in that original document. Securing the rights of women and people of color, among other groups, therefore requires interpreting the values that underlie the Constitution to support them.

To be sure, there are some people of color who themselves are aligned with ultra-conservatives and the claims of originalism except when it doesn’t suit their purposes. One of them is Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. But as Michael Eric Dyson noted on NPR’s Morning Edition:

[W]e have, for instance, on the court now Judge Clarence Thomas, an African-American man to be sure but not committed to the fundamental practices as they have been historically adjudicated and put forth by civil rights communities and other African-American people. So the first qualification is a profound legal commitment to practices of justice. But certainly, that does make a difference in terms of the identity of the person who’s being chosen for that spot.

The current composition of the Court is unacceptable if only based on sheer demographics and the fact that there are many eminently qualified candidates of color for the bench. But it is especially so given the reality that every single decision under consideration by the Supreme Court now, in the recent past, and in the near future has disproportionate implications for women and people of color.

Profound questions are being asked. For example: Who can vote, under what conditions, and facing what kinds of obstacles placed in their way by those who’d rather stifle their voices and de-legitimize their votes? What is “religious freedom” and how freely should this ill-defined and vague notion be used as a means of denying people health care and the rights of women as persons?

Do the people whose bodies contain reproductive organs have a fundamental right to self-determination or are their bodies simply vessels for the production of other bodies even when against their will? Who gets to decide the meaning of “undue burden” in exercising a right, whether that means accessing reproductive health care or exercising the right to vote? (And in all honesty, what would Justice Kennedy know about undue burdens in any case?)

What exactly is “discrimination,” and how hard do you have to work for how many years to prove it? Who gets paid for what, when, and under what conditions? Do government agencies charged with protecting our health and the environment on which we all depend have the authority to actually protect our health and environment? Is reproductive health care actually health care? Is a corporation (or soon a robot?) a person with rights equal to or superseding those who are living, breathing individuals?

This is the real fight. We need more justices with deeper roots in different communities and a broader worldview than white male candidates from Yale or Harvard, ones who are not devoted to the inevitable blind spots of a group of men who lived more than 200 years ago. We need justices who offer perspectives on the facts and realities of people of color and women. And yes, the extent to which they can empathize with people and experiences outside of themselves matters a great deal.

There are more than a few female candidates of color, each of whom are more than capable and qualified to be Supreme Court nominees. Among them are Kamala Harris, attorney general of California, Loretta Lynch, U.S. Attorney General, Melissa Murray, a professor at UC Berkeley, and Jacqueline Nguyen, a judge on the Ninth Circuit.

Moreover, we should not stop there. Since women now make up the majority of this country’s population, we really need, for the very first time in history, to have a majority of women on the Court. Period. This is not about quotas, it’s not about litmus tests. It’s about fundamental human rights, fairness, and the ability to see the world as it really is, and not just from a cloistered building protected from protest.

The right will be aghast at this idea. And truth be told, so will more than a few self-declared liberal men. When you perceive yourself as righteous in every way and the center of the universe, you don’t tend to think of other universes. Because their own needs were reflected in the documents, I am guessing none of the founders lay awake at night thinking about the future implications of the Constitution for women and people of color. I am guessing reproductive and sexual justice, and expanded voting rights for all people, were not of immediate concern and that existential threats like climate change were not remotely in the realm of possibility given that cross-state pollution and fossil fuels came much later. For these and other more expediently political reasons, I don’t think that the four “conservative” justices on the Court lay awake thinking of these things either.

We need people who do think of these things and who can apply core values laid out by the Constitution, using thoughtful and considered judgment, to the issues of the day.

The next nominee—in fact, the next two—should be women of color. Because original intent or no, there are a majority of people out there who do not look like—think, live, or enjoy the privileges of— the Founding Fathers. They have the most at stake in the coming years, and they deserve, finally, to see a court that looks more and more like this America.