The Politics of Fat and Emergency Contraceptives

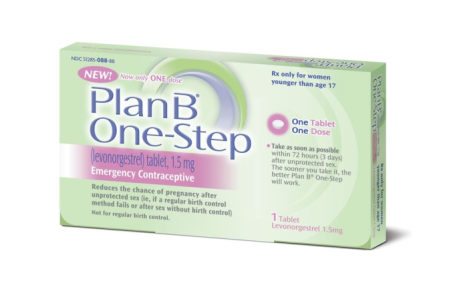

It was reported recently that French drug manufacturer HRA Pharma had found that the emergency contraceptive Norlevo, which has a similar chemical makeup to Plan B One-Step, is ineffective for women over 176 pounds. Here's why I was not surprised.

This piece is published in collaboration with Echoing Ida, a Strong Families project.

I am a fat Black woman from the South. I exist at the intersection of multiple identities that medical research labels “vulnerable populations.” The label “vulnerable population” describes people who are frequently excluded from involvement in medical research, including clinical trials, because they are perceived as difficult to reach by the research community. Despite acknowledging that their research is not inclusive of all groups, the medical industry has a long exploitive history of attributing health disparities to patient behavior and economic inequality rather than admitting that their own prejudices also lead to differential outcomes for “vulnerable populations.” So when it was reported recently that French drug manufacturer HRA Pharma had found that the emergency contraceptive Norlevo, which has a similar chemical makeup to Plan B One-Step, is ineffective for women over 176 pounds, I was not surprised. Medical research, researchers, and commentary do not exist in a vacuum of objectivity; they are shaped by social assumptions and stereotypes that often end up having harmful consequences for “vulnerable populations.”

The labeling of one’s size and obesity status is not objective, nor are the factors isolated. Body mass index (BMI) has long been a magnet for fat-shaming and does not take into account differences in body composition between genders and racial and ethnic groups, and people of color are still disproportionately considered “obese.” Poverty exacerbates barriers to quality health care, thereby increasing the potential for obesity in these communities. With Black and Latino/a populations disproportionately living in poverty, they are at a much higher risk for obesity and more likely to be overweight, especially those living in the South. Poverty not only restricts access to nutrition and health care, but also appropriate reproductive health services and information. This means women of color are less likely to have access to appropriate emergency contraceptives.

According to Princeton’s emergency contraceptive web page, obese women (with a BMI of 30 or greater) became pregnant more than three times as often as non-obese women when using emergency contraceptives like Plan B. For women with a BMI greater than 26, the site recommends they contact a health-care provider for a copper intrauterine device (IUD) within five days after intercourse to prevent pregnancy. Confusion and misinformation already surround emergency contraceptives, especially more popular types like Plan B, but barriers mount depending on one’s race, body type, and class, resulting in often dire consequences for women of color seeking emergency contraceptives.

These findings raise concerns about whether fat women are given adequate knowledge about the proper emergency contraceptives. The medical industry assumes that “obese” women know that a copper IUD would be a more effective alternative to oral emergency contraceptives, can find a physician, and have the device implanted. Though a copper IUD is among the most inexpensive long-term (lasting up to 12 years) and reversible forms of birth control, upfront cost can range from $500 to $900. This presents a potential hardship for these women, who are often unable to acquire such a large lump sum of money. Even with Planned Parenthood’s prorated costs based on income, or even Medicaid, cost is still a barrier for women in rural communities who lack access to health-care professionals and women living in red states that have rejected Medicaid expansion. Even when they gain access to a health-care provider, they may not receive accurate contraceptive information about weight and may encounter poor medical advice that is rooted in the provider’s own racial, gender, class, and fat biases. Additionally, despite the perceived long-term convenience of an IUD, it cannot be inserted or removed without medical assistance. This leaves the judgment to remove the device up to the medical provider, stripping women of their reproductive agency. Lack of adequate access to health care and medical information compounds disadvantage resulting in limited reproductive health options for many women who happen to be considered “obese”—a de facto determination of who is and isn’t deserving of various reproductive health options.

Though over a third of U.S. women are “obese,” they remain underrepresented in contraceptive clinical trials, and at this point there are no clinical trials for an emergency contraceptive scheduled for “obese” women. It is painfully obvious that the medical industry has yet to account for how “vulnerable populations” intersect with one another. “Obese” women included in clinical trials will likely represent the health concerns and needs of white women even though poor women of color are more likely to be “obese” and need to be accounted for, if the medical industry plans to be inclusive. But they seem to have no plans to be inclusive. For example, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine medical trials under-represent Black women, meaning the vaccine on the market is designed to fight HPV strands that are common in white women, rendering it less effective for Black women whose common strands differ. We see this happening in clinical trials for contraceptives as well. Historically, contraceptive research excluded “obese” and overweight women from clinical trials, resulting in a limited body of evidence regarding contraceptive effectiveness and safety in “obese” and overweight women. This means that overweight and “obese” women are prone to receiving improper birth control information largely because their under-representation results in a lack of accurate information about how they are affected. The problems of this lack of information fall disproportionately on the shoulders of women living at the intersections of blackness, poverty, and Southerness.

The irony here is that modern contraceptive knowledge is based on experimentation and forced sterilization of Black women and other women of color during the eugenics movement and its aftermath. Now, when we actually stand to benefit from our inclusion in these trials, the medical industry ignores us. Though “vulnerable population” should imply the increased likelihood of being exploited or mistreated by medical professionals and researchers as it has in the past, it has now come to signify our invisibility and negligent disregard by the medical industry.