Two Women, Different Outcomes: How U.S. Foreign Assistance Policy Harms Women

How is it possible that U.S. foreign aid, which does so much good around the world, can also prevent a woman from receiving an abortion that is legal in her own country?

Consider the stories of two Ethiopian women—Wubalem and Chaltu—who found themselves in similar situations that led to very different outcomes. Both are young, married, and seeking to create the best lives possible for themselves and their families, and both wanted to terminate an unwanted pregnancy.

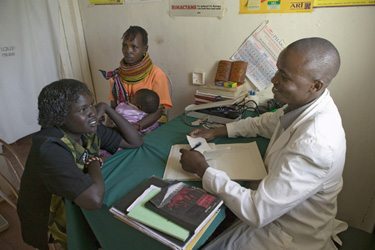

Both Wubalem and Chaltu live only five kilometers from the nearest public health clinic. Under Ethiopian law, both have the right to safe, legal abortion. Yet, because of unnecessarily broad interpretation of U.S. government policy, one was denied this fundamental right.

Wubalem is 22 years old and lives in a rural area of southwest Ethiopia. Shortly after her recent marriage, she was raped by a close relative and further traumatized when she discovered she was pregnant. Desperate to end the pregnancy—and knowing she was legally entitled to do so because it resulted from rape—she went to the nearest public health clinic and requested an abortion.

Wubalem was shocked when health-care workers there told her that the clinic, which receives support from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), does not provide abortions. She would need to travel over 60 kilometers to a facility that offers this legal service. In desperation, she returned home and attempted to end the pregnancy on her own, by inserting a large twig into her uterus.

Two days later, hemorrhaging and with a high fever, Wubalem was rushed to the health center. After almost dying from a severe infection, Wubalem learned that she had a ruptured uterus and will never be able to bear children—a devastating and totally preventable outcome.

Chaltu, also 22, lives in a coffee-growing region closer to the capital city of Addis Ababa. She has two children, the youngest only 10 months old. When Chaltu learned she was pregnant, she and her husband agreed that they could not have another child so soon, especially since Chaltu had a very difficult delivery less than a year ago.

Chaltu traveled with her husband to the nearest public health clinic, which does not receive USAID support, where she was able to obtain a safe, legal abortion on the grounds that another pregnancy could endanger her health. Chaltu returned home the same day after a very simple procedure and resumed caring for her children.

Wubalem and Chaltu are not real women but composites whose experiences mirror those of many Ethiopian women. Their stories provide a stark reminder of the impact of a harmful U.S. foreign-assistance policy on women’s health in developing countries. How is it possible that U.S. foreign aid, which does so much good around the world, can also prevent a woman from receiving an abortion that is legal in her own country?

The answer is overly restrictive interpretation of the Helms Amendment to the U.S. Foreign Assistance Act. In place since 1973, the Helms Amendment states that “none of the funds made available [under the Foreign Assistance Act] shall be used to pay for the performance of abortions as a method of family planning or to motivate or coerce any person to practice abortions.” Legally, this restriction does not extend to abortions performed following rape or incest or when a woman’s life is in danger, as women and girls in these situations clearly are not using abortion as a method of family planning.

But for the past 40 years, USAID and its grantees have implemented the Helms Amendment as a complete ban on abortion. This means that in Ethiopia and in many other developing countries, health-care facilities that receive U.S. government funds treat women only after they are already suffering or dying from a botched abortion, under the umbrella of sanctioned post-abortion care.

For more than two decades I worked for USAID’s international family planning assistance program, including leading the Office of Population from 1993 to 1999. I saw the significant impact of U.S. government assistance on expanding the availability and use of modern methods of contraception in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. But family planning alone will not eliminate the high levels of unwanted pregnancy and unsafe abortion. Women also need access to safe, legal abortion. This is an essential measure to reduce maternal deaths and injuries in developing countries. For the past 14 years, I have been privileged to serve as president and CEO of Ipas, an international non-governmental organization dedicated to providing comprehensive abortion care, including contraception, and to enabling women to exercise their sexual and reproductive rights.

At the International Conference on Family Planning in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in mid-November, I chaired a session on “The Impact of Harmful Legal and Policy Requirements on U.S. International Family Planning Assistance.” The session highlighted how women in developing countries who rely on USAID-supported health-care facilities are denied access to safe, legal abortion to which they are legally entitled—as well as counseling and referral to these services—as part of comprehensive, integrated reproductive health care. Those who are most affected by this denial of services and information are young, poor, and otherwise vulnerable women.

The current restrictive interpretation of the Helms Amendment is at odds with U.S. domestic policy on abortion, whose allowance of government funding for abortion in cases of rape, incest, and life-endangerment is supported by even the most conservative members of Congress.

I call on the Obama administration to correctly implement the Helms Amendment now, by allowing the U.S. Department of State and USAID to support abortion overseas in cases of rape, incest, or to save the life of the woman. This simple act would enable millions of women like Wubalem to gain access to safe abortion care that is legal in their own countries. It would no longer deny the rights of women in other countries to make their own reproductive choices freely and safely.

Failure to act perpetuates an unconscionable imposition of U.S. abortion politics on women in developing countries who are least able to advocate for their own needs.