Jonestown at 40: The Real Conspiracy Is More Disturbing Than the Theories

Rather than parse the definition of murder, or deconstruct the hearts of people long expecting to die, it seems most appropriate to conclude that murder and suicide occurred on that day.

This past month the Church of Scientology explained its ongoing interest in the deaths of 900 Americans that occurred in Jonestown, Guyana, 40 years ago on November 18, 1978. STAND (Scientologists Taking Action Against Discrimination) published a four-part series that presents its best evidence for asserting that those deaths were mass murder rather than collective suicide, as initially reported in the news media.

While Scientology may have a stake in how this story is told, the series actually raises two important questions. First, how in fact did the residents of the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project—better known as Jonestown—die? While some journalists and theorists were among the first to ask this question, it’s just now coming to the fore in mainstream media analyses of the events.

The second question is—or should be—what was the motive of the perpetrators, if the deaths were truly murder? As the STAND series asks, “What purpose could the deaths of so many people serve?”

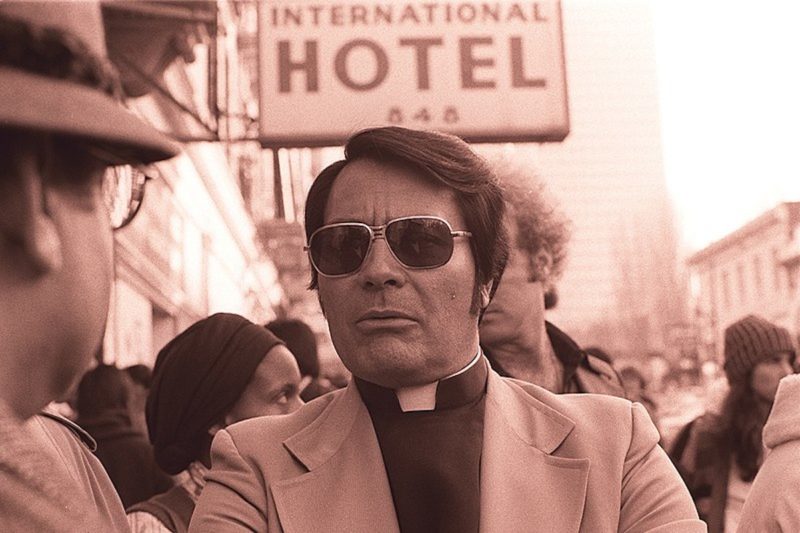

A number of writers have offered various theories: that the deaths masked a “hit” on Congressman Leo Ryan, who had co-sponsored legislation to rein in the CIA; that they hid the fact that Jonestown was a CIA mind-control experiment; or that Jim Jones was a rogue CIA agent who killed everyone to prevent his secret from coming out. Comedian Dick Gregory claimed that forces from the CIA and the FBI used the Jonestown bodies to smuggle heroin into the United States. I catalogued these and other theories about motive in a 2002 article.

Most of these explanations have been debunked. Matthew Thomas Farrell painstakingly assessed the mind-control account offered by John Judge, who wrote what has become the ur-text on conspiracy memes about Jonestown. An analysis of Dr. Leslie Mootoo, the Guyana pathologist who investigated the Jonestown deaths, reveals numerous discrepancies in his reports. And Jeff Brailey, who served in the military as part of the humanitarian task force assigned to remove the bodies from Jonestown, thoroughly discredited Charles Huff, one of the bulwarks of the Scientology narrative.

Yet, in all of these investigations, one group of conspirators has been neglected—Jim Jones and the leadership circle in Jonestown. Ironically, this is the conspiracy for which the most evidence exists. A plan had been devised, cyanide had been acquired, and dress rehearsals occurred, all with the complicity of a number of individuals. Unfortunately that cohort included my older sister Carolyn Layton and my younger sister Annie Moore (both of whom died in Jonestown). But quite a few others were part of the conspiracy as well, including the team of young men from Jonestown who ambushed Congressman Ryan and his party as they attempted to leave.

Knowing the identities of the conspirators still doesn’t make their motivations transparent. What does seem evident is a belief in the necessity of self-sacrifice—whether to prevent a greater disaster (such as being tortured by outside forces) or to protest the conditions of an inhumane world.

This brings us back to the first question: Was it mass murder or collective suicide? Certainly more than 300 children were murdered. They were killed first, primarily by medical staff who used syringes to squirt poison into their mouths. But this staff was aided by parents, make no mistake about that. In addition, a number of senior citizens are reported to have been injected with poison, but it’s impossible to determine how many.

This leaves the problem of how many adults voluntarily drank the “Kool-Aid.” Suicide is, of course, called into question if they were surrounded by armed guards, though the guards themselves died at the end by ingesting poison. The presence of hypodermic needles at the site also argues against suicide.

At the same time, how do we account for those residents who silenced the lone voice protesting the mass deaths? Christine Miller argued with Jim Jones during the last moments, but her objections were shouted down by others. One woman told her “You must prepare to die.” And one man tearfully announced, “We’re all ready to go. If you tell us we have to give our lives now, we’re ready—at least the rest of the sisters and brothers are with me.”

Finally, one indisputable question remains. Skip Roberts, the Guyanese police commissioner responsible for investigating the deaths in Jonestown, observed: “Jones was clever. He had people kill their children first. Who would want to live after that?”

Indeed, who would want to live after witnessing the death of the future?

Undoubtedly some individuals were either coerced into drinking poison, or were injected against their will. We don’t know how many. Some individuals did step up voluntarily, especially after seeing their loved ones die and perceiving the imminent end of all they had worked for. Again, we don’t know how many.

Rather than parse the definition of murder, or deconstruct the hearts of people long expecting to die, it seems most appropriate to conclude that murder and suicide occurred on that day. That paradox is what has given rise to the proliferation of alternative theories. As political scientist Michael Barkun writes in A Culture of Conspiracy, the conspiracy theorist’s view is both frightening and reassuring.

It’s frightening because it magnifies the power of evil …. At the same time, however, it’s reassuring, for it promises a world that’s meaningful rather than arbitrary.

Thus, it’s more comforting to believe that nefarious outside forces murdered everyone than to accept the concrete evidence that insiders were responsible for what happened. Hateful enemies rather than loving parents perpetrated the atrocity.

Forty years later, the deaths in Jonestown seem neither meaningful nor arbitrary. They are evil insofar as fundamentally decent human beings inflicted great horror and suffering on other human beings, and on themselves. Aristotle’s definition of tragedy seems the best way to characterize the event: an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude. That magnitude remains unimaginable to this very day. For some, the only way to cope with that reality is to create a new one.