Why No One Noticed I Was Hungry

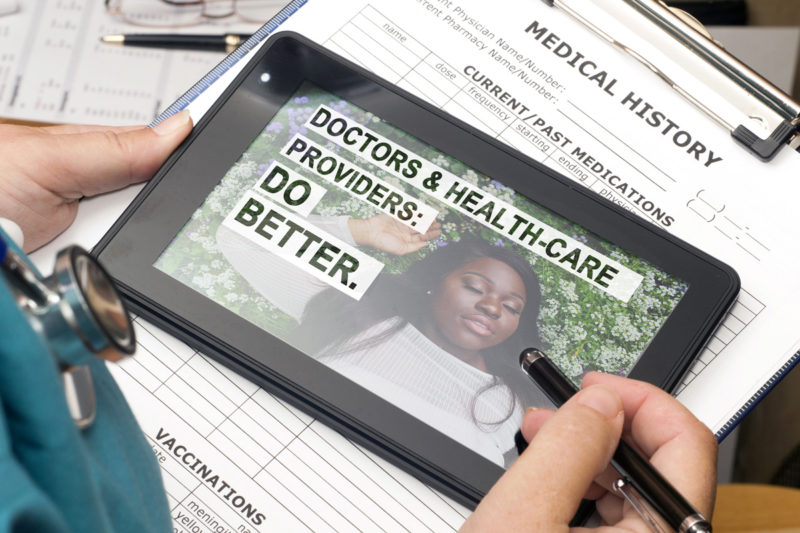

Disordered eating, especially restricting and anorexia, is too often thought of as a thin, affluent white woman’s problem.

For more anti-racism resources, check out our guide, Racial Justice Is Reproductive Justice.

You’re probably just doing something wrong. Maybe you need more structure. Have you ever considered Weight Watchers?

The words stung. I had been waiting two months to be seen by the only in-network endocrinologist that was available before the end of 2018. Before his suggestion, I’d spent the morning explaining to him and his resident that I feared I may have a thyroid issue. My mom had thyroid cancer and my paternal aunt has hypothyroidism; another doctor had found several small cysts on my thyroid and suggested I get it checked yearly.

I hadn’t thought much of it until I began feeling endlessly fatigued, my period became irregular and more painful, and I completely plateaued trying to lose weight. This new endocrinologist told me that thyroid medication isn’t a magic pill to lose weight, refusing to run more than two thyroid panels or call for an ultrasound. OK, but what about my other symptoms? He told me not to worry about those and turned to leave. Before he closed the door, he urged me again to consider Weight Watchers.

I had told this doctor what I’d told every doctor I had seen that year: I’ve tried every diet I could find including keto, veganism, juice cleanses, intermittent fasting, among even more obscure fads. I proudly showed the endocrinologist my calorie tracker when asked about my nutrition and exercise routine, but I could tell he didn’t quite believe what he was reading. Not once did he—or any other medical professional, for years—consider that my diet and exercise were themselves symptoms of a disease.

Writing this in January 2019, I’m now in recovery from what my dietician and therapist call an “other-specified eating disorder.” I have committed myself to build a healthy relationship with food and with my body—to never diet again. I’ve also been diagnosed with endometriosis, several vitamin deficiencies, major depression, and generalized anxiety. These new diagnoses explain the period problems and fatigue. They don’t explain why it took years for a doctor to notice my disordered eating.

Disordered eating, especially restricting and anorexia, is portrayed as a thin, affluent white woman’s problem. Not all patients with eating disorders look as emaciated as the actresses we see in Lifetime movies. But many doctors don’t seem to know this. Despite research confirming that people with a history of obesity—a term I normally wouldn’t use, if not for its medical context in this case, because it is both stigmatizing and arbitrary—are at significant risk of developing eating disorders, their symptoms are far more likely to go untreated. This is because doctors have a hard time seeing past the size of their fat patients, even in diagnosing completely unrelated conditions. Medical trauma because of fat-shaming doctors can be so bad that many fat people avoid going to the doctor altogether, opting to deal with health issues alone rather than face the reality that many health-care providers would not take their symptoms seriously. This mistreatment by medical professionals is only exacerbated for Black and brown patients, who face a slew of problems when seeking care.

I am what many in the fat activism community call “small fat,” meaning I am technically larger than what society deems the acceptable body size, but I am not as fat as many others. Despite my countless bad experiences with doctors dismissing my health concerns and suggesting weight loss, I have a privilege that other, fatter patients are not afforded. I eventually got diagnoses for the illnesses that were causing me major issues, but others may still be struggling to find a doctor that can look past their weight.

Doctors’ obsession with weight loss also ignores the fact that diets that severely restrict food (such as the commonly prescribed 1200-calorie diet) are damaging to our health. Not only is dieting bad for you, but more and more research is revealing that it doesn’t even work. After analyzing 31 long-term dieting studies, UCLA researchers determined that the majority of people who lose weight on any number of diets gain it back and then some. In fact, they argue that not dieting at all would be healthier than losing and gaining weight in an endless cycle, as is common among chronic dieters like me. Weight cycling is linked to many of the health issues that doctors are constantly regurgitating as the risks of obesity: cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, and altered immune function. It may be possible that the very diets that doctors are prescribing are making their fat patients sick.

Even if that endocrinologist didn’t think I was too fat for an eating disorder, he may have thought I was too brown. It is a widely believed myth that only white women get eating disorders. It is also patently false that only white women suffer through body image problems so severe that they lead to restriction and disordered eating. In fact, eating disorders in people of color are often triggered around puberty, when we begin to realize just how different we look from our white peers. As a woman of Lebanese descent, I’ve always been acutely aware of the pressure Lebanese women feel to conform to Western beauty standards. This manifests in the country’s huge cosmetic surgery industry, which historically focused on rhinoplasties but is moving toward body procedures such as butt implants and labiaplasty. Banks in Lebanon even offer loans specifically to cover cosmetic surgery.

Growing up in an affluent, conservative, and white city in the United States, I knew I stood out. When I hit puberty, it was obvious that my body was developing differently than my friends’—another thing that made it harder for me to assimilate. Losing weight could at the very least make me fit into the same clothes as my classmates, even if I couldn’t hide my financial situation or my heritage.

The point is that body image problems and eating disorders don’t discriminate. But doctors who treat them often do. That eating disorders are only a white woman’s problem is a dangerous stereotype that health-care providers must overcome in order to provide equitable care for all of their patients.

The erasure of people of color and larger-bodied people with eating disorders exacerbates bad treatment from doctors. Instead of listening to and treating our symptoms, they prescribe weight loss again and again, leaving many health concerns unaddressed—both those related to disordered eating and those unrelated entirely.

And they definitely don’t notice we’re hungry.