How ‘Roe v. Wade’ Started With Students, Birth Control, and a Pay Phone

A group of women graduate students in Texas knew not getting pregnant was key to getting their education. When they started a network to help women get birth control via a public phone, they unleashed something even bigger.

The road to Roe v. Wade arguably started in the living room of University of Texas at Austin (UT) science graduate student Judy Smith in the fall of 1968. As the late Smith’s longtime boyfriend Jim Wheelis joked, “If I had known this would be historical, I would have taken notes.”

In 1965, the Supreme Court ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut that a constitutional right to privacy protected a married couple’s right to purchase birth control, overturning the state law that prohibited the use of contraceptives. Similar protection was extended to single women in Eisenstadt v. Baird seven years later, in 1972.

But married or not, young UT students sought the pill in the late 1960s from doctors on and off campus. Smith and another UT graduate student, Victoria Foe, met in early 1968 while working with one of the few male faculty who accepted female students. Both had a hard time finding an advisor in the science program. Male faculty refused to take on female students, arguing that women would become pregnant and drop out of school. Smith and Foe quickly realized that control over reproduction directly affected a woman’s education.

While the pill was available to married women in the late 1960s from private doctors and at the UT health center, doctors did not prescribe it freely. According to Foe, some doctors believed a “woman who was taking birth control pill was willing to sleep with you or that you could fondle her.” Foe remembered that there were “doctors who would do one of two things: They would either give you a lecture on morality as if it was any of their business or they felt they could make a pass at you.”

Smith saw the demand for easily accessible contraception as a starting point for a women’s rights organization in Austin.

Early in the semester, Smith approached Foe and explained that she was holding a meeting at her house to discuss women’s issues. That night was the first meeting of the group Austin Women’s Liberation, and the women agreed their first goal was to compile a list of doctors who prescribed birth control without harassing women.

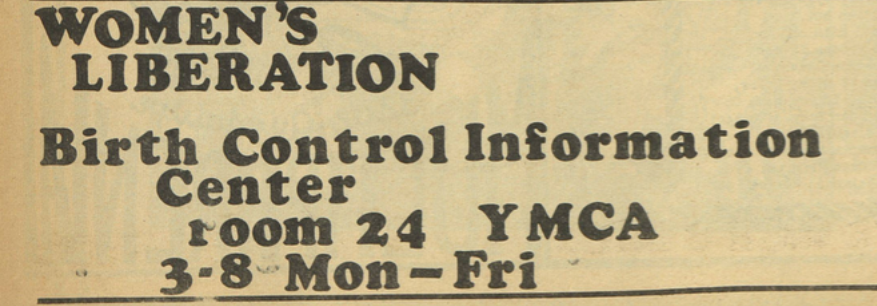

By November, the Birth Control Information Center (BCIC) was operating in the University YMCA in a tiny, closetlike space next to the underground radical newspaper The Rag. According to Foe and Wheelis, the women tracked which doctors were accused of sexual harassment and advised women on who willingly prescribed the pill. The group ran advertisements in The Rag, which listed the BCIC’s number as the pay phone in the hallway of the Y. The birth control service had office hours where people could drop in or call, and if no volunteers were available, the newspaper’s staff would take messages and get them to the BCIC.

Soon after opening the BCIC, Foe and Smith began to receive calls from women seeking abortions. Abortion had been illegal in Texas since the mid-19th century. Texans with means in the late 1960s traveled to New York or England for the procedure. However, broke college students and working-class women in the larger Austin area couldn’t just pick up and travel for an already expensive medical procedure. According to articles in The Rag, abortions cost anywhere from $150 to $1,000 in Texas. Many women opted to travel to England, where they were sometimes guaranteed their abortion would be performed by a medical professional. But the airfare alone cost hundreds of dollars.

Foe herself had an abortion along the Texas-Mexico border and knew that doctors paid local officials to look the other way. As a result, Smith and Foe traveled to the Mexican town of Piedras Negras across the U.S. border to assess which doctors performed the procedure. As Foe recounted, the BCIC gave women access to licensed doctors operating out of medical clinics in Mexico, complicating the idea that dirty and corrupt back-alley abortionists performed all abortions before legalization.

Once the women located and vetted doctors, the BCIC evolved to include abortion referrals. Women anonymously called the Y payphone and left a message with a BCIC volunteer or a Rag staffer who happened to answer.

As Wheelis, Foe, and former Rag staffers recalled during interviews, the students who rented space in the university Y knew the payphone was bugged. Because The Rag published socialist, radical, and New Left articles that often directly challenged the leadership of then-President Lyndon B. Johnson, the UT Board of Regents—the university’s governing body—and the FBI kept a close eye on the groups organizing out of the space across the street from campus.

Smith returned calls from a secure line, sometimes adding her home phone number to the newspaper ads. As Wheelis recalled, women called Smith at home to set up an appointment. Smith then borrowed Wheelis’ truck to transport the women to the clinics, occasionally in San Antonio, Waco, or Dallas, but mostly in Mexico.

Although the handful of BCIC volunteers kept records, they did not preserve them over the years and there’s no way to know how many women the BCIC served between 1968 and 1973. While the majority of the women successfully ended their pregnancies, volunteers at the BCIC remembered the occasional failed abortion, such as that of one woman who remained pregnant after the procedure; however, the activists excused this error, thinking she must have been carrying twins.

The women continued to help other people access abortion into the 1970s, but Smith and Foe took different paths in their continued activism. Smith continued to focus on helping women on a community level, and Foe began to work at the Texas legislature to help representatives tasked with rewriting the Texas abortion laws.

While the women at the BCIC continued the referral service, the UT Board of Regents took The Rag to court in an attempt to ban the sale of the paper on campus. The volunteer student- and community-operated staff challenged the university head on and won its case in September 1970. A group of 20-something-year-old college students won in court, and Judy Smith believed women could follow their lead by challenging the Texas restrictions on abortion.

Smith met Sarah Weddington, the attorney who would argue Roe v. Wade before the Supreme Court, through their boyfriends, who were law school classmates. Weddington could not find work as a lawyer after graduation, and Smith needed someone willing to take on the case for free.

This moment is where the well-known narrative of Roe (which was decided on January 22, 1973), begins. Weddington agreed to file the case, and the trio worked with Linda Coffee of Dallas, who was Weddington’s former law school classmate and clerk to U.S. District Judge Sarah T. Hughes. They were hoping that filing the case in Dallas, against District Attorney Henry Wade, would land them in front of Hughes, who they hoped would be friendly to their case.

Their gamble paid off. Foe, Smith, the other BCIC volunteers, and Weddington were in their 20s when Roe was filed. Most of them were students.

Speaking about today’s young activists in a phone interview for my research about Texas abortion organizing, Foe added that it often only takes a small group of people working hard to make change.

“The worst thing you can do is think, ‘There is nothing I can do about this.'”