Rosie and Me: Remembering the Hyde Amendment’s First Victim

Our abortion stories link us across time and distance, connecting us to our ancestors and those who follow.

I had an abortion. Every time I tell my story, it gets a little easier because I know that by sharing my story I can help others—other women, other Latinxs—feel like they are not alone.

At one of the most difficult times in my life, I found myself pregnant. I had survived abuse in Mexico, returned to experience homelessness and depression in Colorado, and then learned that my father died, leaving my mother destitute in Venezuela. As I dedicated myself to piecing my life back together, I brought my mother—who lives with multiple sclerosis and uses a wheelchair—to live with me so I could care for her. I had three part-time jobs, no benefits, and neither of us had health insurance. Then, I learned that I was pregnant.

Due to my own chronic disability, doctors warned me that carrying a pregnancy to term would mean being bedridden for six months during pregnancy and three months after giving birth. As an immigrant with limited resources and support, caring for my disabled elderly parent while managing my own chronic disability, I couldn’t imagine caring for another life. My socioeconomic status, migration, and medical condition were the backdrop for making one of the hardest decisions in my life. In many ways, I didn’t have a “choice”—and it is my hope to change that for those who come after me.

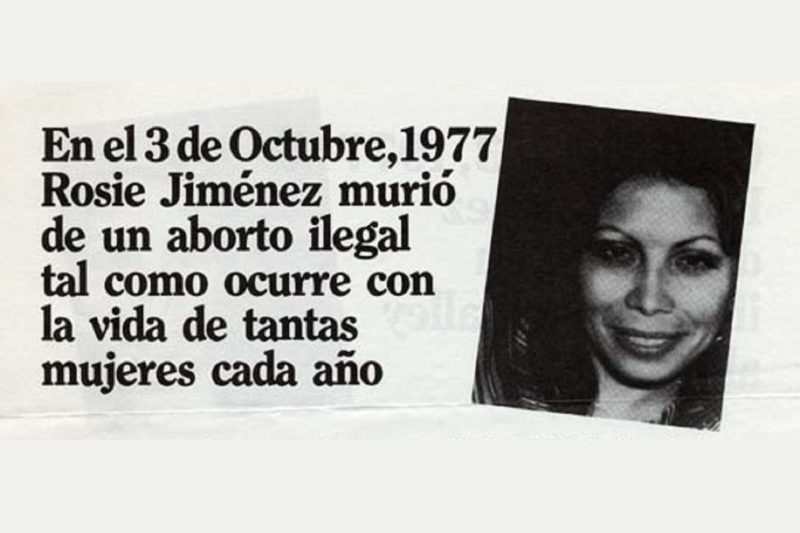

Today on October 3, I think of another story and someone who came before me: Rosie Jiménez.

Forty years ago on this date, Jiménez, a young Chicana, became the first known person to die after Congress passed the Hyde Amendment in 1976, banning the use of federal Medicaid insurance for abortion in all but a few narrow circumstances.

Our stories link us across time and distance, connecting us to our ancestors and those who follow. Jiménez’s story is one reminder of the many ways that bans on abortion coverage threaten the health and lives of Latinas and all who may need abortion care.

Rosie Jiménez was a Chicana living in McAllen, Texas. The daughter of migrant farmworkers, she was a single mother raising her 5-year-old daughter while studying to become a teacher. She became pregnant after Roe v. Wade legalized abortion, but unfortunately it was also after the U.S. Congress had first passed the Hyde Amendment, banning Medicaid from covering abortion.

Because Medicaid wouldn’t cover her procedure at a safe and legal clinic (the Hyde Amendment had gone into effect mere months before) Rosie turned to an unsafe abortion that claimed her life. She had her entire future ahead of her, including raising her daughter to be healthy, happy, and supported, and pursuing her career. In fact, she was so committed to a better future for herself and her daughter that she died with a $700 scholarship check in her purse.

Like the stories of many of the one in three U.S. women who have abortions in their lifetimes, Rosie’s story points to systemic barriers in a way that no statistic can do justice.

In the 40 years since Rosie’s death, some things about abortion in the United States have changed. Others have not. Congress has reauthorized the Hyde Amendment every year, with devastating consequences. We now know that restricting Medicaid coverage of abortion forces one in four poor women seeking abortion to carry an unwanted pregnancy to term.

To make things even worse, state politicians have passed hundreds of new restrictions that force clinics to shut down, delay access to care, and make it more expensive and difficult to get abortions. Women will use the information available to them to make the best health decisions for themselves and their families. Abortion is safe and effective. But if someone doesn’t have access to a range of abortion options and accurate health information, there may turn to ineffective or dangerous methods of ending a pregnancy.

While a woman who is denied coverage for abortion care under Medicaid might not share Rosie’s fate today, denying coverage for an abortion can push her to the economic brink when she’s already living paycheck to paycheck. The Hyde Amendment creates an often insurmountable barrier to abortion for those across the country already struggling to get affordable health care, and it disproportionately affects low-income people, youth, people of color, immigrants, and those who live in rural communities.

They are women like me, though our experiences with pregnancy and parenting are complex. I am grateful that I could access safe and legal abortion care when I needed to, and at the same time I recognize that my decision didn’t happen in isolation, it was connected to the barriers and challenges I faced.

I tell my story and share the stories of other Latinas, so we can disrupt the culture of shame that surrounds abortion. Stigma hurts. I share my story not because it is unique, but because it isn’t.

Latinas’ stories continue to be powerful reminders of all people who are denied the human right to safe, legal, and affordable abortion care. In fact, the stories of Texas Latinas struggling to access abortion care after Texas passed its notorious clinic shutdown law HB 2 helped persuade the U.S. Supreme Court to affirm in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt that a woman should be able to access abortion with respect and dignity and without needless barriers. And in state legislatures across the country, more individuals and organizations are sharing abortion stories to help lawmakers understand the impact of laws that push abortion out of reach. The decision to end or continue a pregnancy is too important and too personal to be left up to politicians to decide for us.

Telling stories is a way to remember and learn from the past. Stories can also light the way to a brighter future.

In the future I imagine, every person who wants to become a parent has the respect, resources, and health services to do so. In the future I imagine, every person who decides to end a pregnancy also has access to the care they need—without stigma or barriers, covered by insurance, and provided with compassion and respect. And if telling our stories will help get us there—and I believe it will—then that’s what I’m going to do.