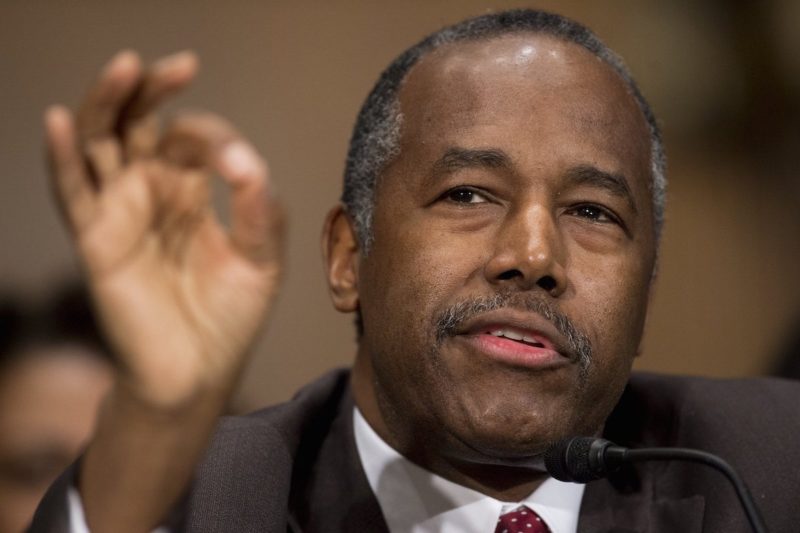

America the Ahistorical: Ben Carson and the Dangers of Willful Ignorance

There’s a cautionary tale in this we should heed if we don’t want to validate revisionist history that makes slavery seem like an undesirable minimum wage job.

In a country where politicians routinely usurp doctors’ roles and pretend to know what’s best for women’s bodies, some policymakers and legislators are now masquerading as historians.

Two recent examples: We’ve heard the new secretary of Housing and Urban Development’s confusion about the difference between immigrants and enslaved people (to wit, “immigrants who came here in the bottom of slave ships, worked even longer, even harder for less”). Spouting the garbled nonsense that’s his unfortunate calling card, Dr. Ben Carson lumped in millions of kidnapped Africans with those huddled masses who, yearning to breathe free, packed their own bags and came to the New World under their own steam. Also, as Rewire‘s Teddy Wilson recently reported, a Missouri legislator proposed a bill that would place an exhibit about abortion in the state museum—and require it to be in close proximity to displays about slavery. The logic, you say? Because under the original U.S. Constitution, enslaved people counted as three-fifths of a person and “many people” say a fetus “is not a person until he or she takes her first breath,” according to state Rep. Mike Moon (R-Ash Grove).

Welcome to the latest iteration of the Culture Wars. And the 2017 edition is promising to be a doozy.

The signs are popping up with alarming frequency. An Arkansas legislator wants to block schools from teaching the works of the late social historian Howard Zinn, author of the 1980 classic A People’s History of the United States. In Chicago, a February seminar that taught high school students lessons from the civil rights movement faced pushback from parents and pundits who claimed the optional workshop was “racial indoctrination.”

These incidents may appear random or unconnected. Maybe you think they are lapses of knowledge that can be corrected with a good reading list, better public education where teaching history is not sidelined (no, that high-school civics course was not enough), and common sense. Fair enough. They certainly are symptoms of widespread historical ignorance in the United States, but they are also symptoms of a vocal minority who reject U.S. multiculturalism, narratives that shift our national stories from Big Men History, and social and political change.

And when ignorance could become enshrined in federal or state policy, that’s dangerous.

Let’s consider Secretary Carson and his much-discussed slavery comments. His history-challenged remarks may be the ramblings of a man who thinks he knows more than he does, a trait common among President Trump and his administration’s officials. Also, to be fair, he’s not the first to refer to enslaved people as laborers without the context that U.S. slavery was a “special” kind of hereditary, stigmatized work based on white supremacy. It was not unusual for slaveholders to call the enslaved “servants,” and in more contemporary times, a Texas textbook called them “workers” here to toil on the agricultural plantations of the South. So who can blame an elementary school reader who believes that enslaved people got some wages and weren’t chained to a job simply due to stigmatized African ancestry?

We CAN blame educated, accomplished adults like Carson, who should know better (though he has defended his statement, saying that he refers to anyone from a foreign place an immigrant), but book learning and credentials don’t necessarily cure ignorance, especially when someone is politically invested in the “not-knowing.” We can blame conservatives’ many culture wars for promoting “Western civilization” classes and not acknowledging that slavery fueled United States and global development, while questioning the need for Black studies. We can also blame historic preservationists and museum curators who romanticize the Old South for making slavery—along with evolution, LGBTQ rights, and sex ed—one of the most contested topics in school curricula and in our museums.

Depicting the horrors of slavery accurately is no small task. It requires stitching together stories of people whose literacy was outlawed—and who therefore could not document their own lives for posterity, in most cases. Representing the enslaved well requires sifting through the racist claptrap of what their oppressors said about them. And it demands a belief in Black humanity, which plenty of cultural sites around the country still get wrong. They can’t stomach the new history told “from below,” are stuck in the past’s moldy scholarship, and prefer Scarlett O’Hara tales to stories like those of Celia, a young enslaved woman in Missouri (who killed her owner after years of sexual abuse and who is the subject of new and exciting research). Imagine if Rep. Moon was pushing for a display about Celia in the Missouri state museum rather than angling for one that would compare Black people to fertilized eggs.

The problem with Carson’s comment, and others like it, is that ignorant officials have higher-than-average odds of making or supporting ignorant and often devastating policy. If you need evidence, just take a look at the vast array of reproductive rights restrictions. And while I’m surprised that Carson even mentioned slavery as a labor issue—he has repeatedly compared abortion to enslavement—the question is whether this idea of “enslavement as immigration” affects his assumptions and decisions, or those of the government workers paid to do his bidding.

Because if you extend his comments to the next possible rhetorical step, then it may seem natural to wonder why these “African-American immigrants” have not fared as well as those virtuous and striving (meaning white) immigrants who not only pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, but probably made those very bootstraps in a textile factory.

We don’t need the nation’s top housing official or his team to think such thoughts, when Black Americans make up a disproportionate number of public-housing residents. Racism has already played historically harmful roles in creating the extreme segregation in the nation’s “projects.” In major cities such as New York and St. Louis, public housing was designed as separate majority-white communities and majority-Black communities, with some places evicting whites to “blacken” the complexes and many more restricting Black residents from buying or living in mostly white zones. But few seem to remember that public housing was once largely for white folks.

Carson’s comments and the proposed bills that seek to mandate what students learn, like the Howard Zinn one in Arkansas, are not surprising when we understand that politicians have always dabbled in rewriting history. And there’s a cautionary tale in this we should heed if we don’t want to validate revisionist history that makes slavery seem like an undesirable minimum wage job.

The South’s early segregationists were arguably the preeminent and most powerful shapers of historical narratives. By the end of the 19th century and the beginnings of the 20th, they were equipping state historical societies with staff and improving buildings to preserve documents from the early years. They paid special attention to documenting the halcyon days before the War Between the States, when Black “servants” (read: enslaved people) were kept in line by benevolent white benefactors. These historians-in-training paid homage to a plantation society that, in reality, primarily benefited white elites but gifted all whites with a sense of racial superiority. Before the Civil War had even ended, South Carolina’s state archive was pouring resources into compiling lists of Confederate soldiers. They built towering monuments to Robert E. Lee and the “boys in Grey” to memorialize their narrow, selective version of history not just in paper, but stone, brick, and memory. They were literally making history.

I don’t need to tell you that there was little mention of those Black people who brought the war to fruition by their existence and their acts of sabotage, fugitivity, and easily recognizable resistance. This was “alternative facts” at its best. But even in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, historians such as Elsa Barkley Brown have shown how Black communities in places such as Richmond, Virginia, populated public space with their own buildings, parades, and media that celebrated Black achievement. Historians of the Black American experience are still refuting alternative facts that say, for example, that the Civil War wasn’t about slavery but about states’ rights (not that it has to be about one or the other).

Our museums, our schools, and their textbooks are fronts in a war over what history we tell and what we believe—just as are the halls of Congress, the streets on which we march, or the clinics in which we receive health care. And this is not news to those of us who are actually trained historians. History is not just a set of dates and facts that schoolchildren cram to remember and recite; it’s a set of accepted ideas curated and promoted by a small group of people, and history museums and textbooks are symbols and sites for re-creating and playing out social relationships, even and especially the unequal ones.

People don’t leave their identities at the door when they enter a museum or read a book. Or when they make laws.