False Choices and the Legacy of ‘Gonzales v. Carhart’

Gonzales v. Carhart continues to be the single greatest jurisprudential threat to Roe v. Wade and abortion rights. And the severity of that threat is once again playing out in states across the country.

When the U.S. Supreme Court in Gonzales v. Carhart upheld the federal “partial-birth abortion” ban, a law that criminalizes a form of later abortion known as intact dilation and extraction terminations (D and X), the Court lit a dangerous path. The product of an escalating anti-choice campaign in the states to roll back abortion access—much like the one we’re witnessing today, nine years after the decision—the federal law provides no exception for the health of the patient. And conservatives today are using the precedent of false choice set by Gonzales to chip away at reproductive rights even further.

The conservative majority of the Supreme Court reasoned in 2007 that the D and X ban posed no undue burden on abortion rights because if a patient needed a later abortion, they still had the option of other procedures, including the more common dilation and evacuation (D and E). Or they could seek an earlier abortion, the Court said.

These were radical statements for the justices to make. To begin with, Gonzales set the dangerous precedent of upholding a pre-viability abortion ban that contained no health exception for the patient, in direct contradiction to Roe v. Wade. The 2007 decision also questioned whether a health exception to any procedure was ever necessary to begin with, leaving open the possibility for challenges to other forms of abortion procedures or even full-on abortion bans. Finally, the Court grounded its decision in the ultimate straw-man argument in abortion politics: that patients in need will always have other “choices” available to them. Worst of all, the conservative majority perpetuated this argument while in the midst of the fallout of culture wars of the 1990s, which included the stated purpose of re-criminalizing abortion altogether.

In those ways, Gonzales continues to be the single greatest jurisprudential threat to Roe v. Wade and abortion rights. And the severity of that threat is once again playing out in states across the country.

Later this summer, the Kansas Supreme Court will hear arguments in a case challenging SB 95, the state’s ban on so-called dismemberment abortions—the very D and E procedure relied upon by the Gonzales Court as an available alternative when it upheld the federal “partial-birth abortion” ban. Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback (R) signed the measure in April 2015, but the measure remains blocked by the courts.

D and E abortions are the safest and most common form of later abortion available to patients, and they are also the most recent target by anti-choice advocates to end abortion rights. Kansas was the first to try and outlaw D and E abortions, but other conservative-led states have been quick to follow. One week after Brownback signed SB 95, Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin (R) signed a similar restriction into law. That measure was also blocked in state court. Lawmakers tried, but failed, to pass a similar measure in West Virginia.

Meanwhile Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant (R) signed an identical measure into law just last week.

Should these measures eventually end up in front of the Supreme Court—and we are a long way from that happening at this point, so let’s be clear here—by the Court’s logic in Gonzales, those restrictions would not constitute an undue burden given the “availability” of other abortion methods, including medication abortions. Never mind that medication abortion is only used up to ten weeks’ gestation, meaning that such restrictions make second-trimester abortion broadly unavailable.

And medication abortion itself is not a guarantee. So far, 37 states have put some kind of restriction on the dispensing or use of medications to induce abortion. Oklahoma tried to outlaw the practice entirely. And with states like Arkansas, North Dakota, and now Alabama trying to whittle down the window of fetal viability earlier and earlier—many arguing that it begins at conception—the “availability” of medication abortions for earlier terminations, or of any abortions at all, is increasingly becoming theory rather than practice. Attorneys defending pre-viability bans in North Dakota and Arkansas have gone so far as to argue the “choice” offered to patients needing abortion care is to carry their pregnancies to term and then simply hand over any baby from a live birth to the state.

Meanwhile, the country waits for the Roberts Court to issue its ruling in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, a case challenging portions of a Texas law that is designed to close reproductive health clinics, but whose supporters promote “patient safety.” Since its enactment, the Texas law has decimated abortion access in the state. It has closed all but a handful of clinics in the state, forcing patients to travel out of state for health care or pushing them into more expensive, later abortions—such as the procedures Oklahoma, Kansas, and Mississippi are trying to outlaw.

In other words, access is being restricted on both ends of the timeline, leaving no room in the middle for patients to actually get care.

The Texas law also inspired dozens of copycats across the country, leaving states like Mississippi with its only abortion clinic open via court order and clinics in Wisconsin, Alabama, and elsewhere waiting daily to see if they can remain open pending a decision from the Roberts Court.

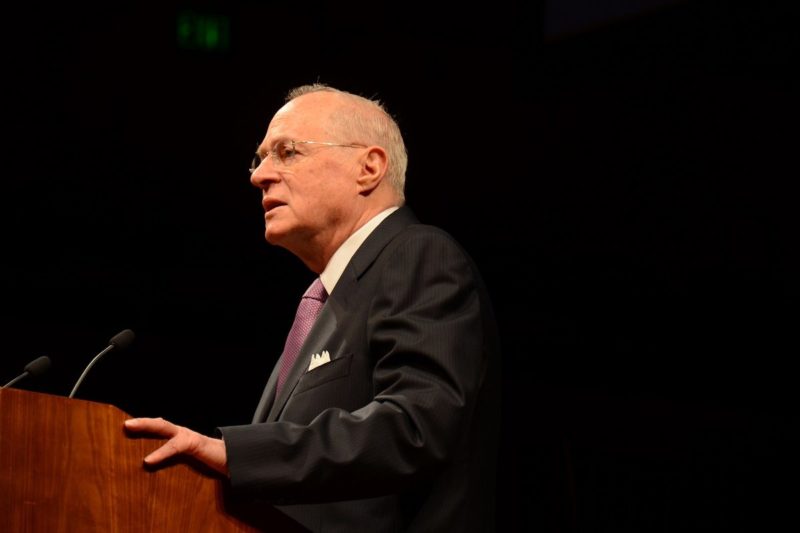

And this is the legacy of Gonzales. Nine years later, anti-choice lawmakers in states across the country push more abortion restrictions under the guise that patient “choice” remains, when increasingly the opposite is true. Even Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, no friend to abortion rights, noted the increasingly holographic nature of “choice” in this country during oral arguments in Whole Woman’s Health, when he expressed concern that Texas was the one state in the country where earlier medication abortions were declining, due in part to the lack of abortion clinics in much of the state.

I’m not willing to go so far as to suggest that we’ve reached a tipping point for the Roberts Court’s anti-choice conservatives in the attack on reproductive autonomy in this country. But if even Justice Kennedy shows discomfort at the deceptions the anti-choice community has employed in devastating abortion access while at the same time promoting the idea of “choice,” then perhaps not all hope is lost that the jurisprudential siege on Roe and abortion rights will soon recede.