How Justice Kennedy Set the Stage for D and E Bans in ‘Gonzales v. Carhart’

In Gonzales, we were handed a devastating loss that set the stage for waves of restrictive and unscientific attacks on abortion rights.

In 2000’s Stenberg v. Carhart, the United States Supreme Court struck down a Nebraska statute banning “partial-birth abortions,” a phrase coined by anti-choice activists to describe a relatively uncommon variation of dilation and evacuation abortion (D and E) known by providers as an “intact D and E.”

The Nebraska law, the majority in Stenberg wrote, unduly burdened abortion rights, in part because it was a pre-viability ban that contained no exception for the health of the pregnant person. Seven years later, the Supreme Court would once again take up the issue of intact D and Es—this time in Gonzales v. Carhart, a case that challenged the federal Partial Birth Abortion Act of 2003.

The law in question was modeled largely after the stricken Nebraska statute; therefore, like Stenberg, Gonzales should have been another victory for pro-choice advocates. Instead, we were handed a devastating loss that set the stage for waves of restrictive and unscientific attacks on abortion rights. Those restrictions have come to a dangerous crest with the anti-choice community’s campaign against D and E abortions.

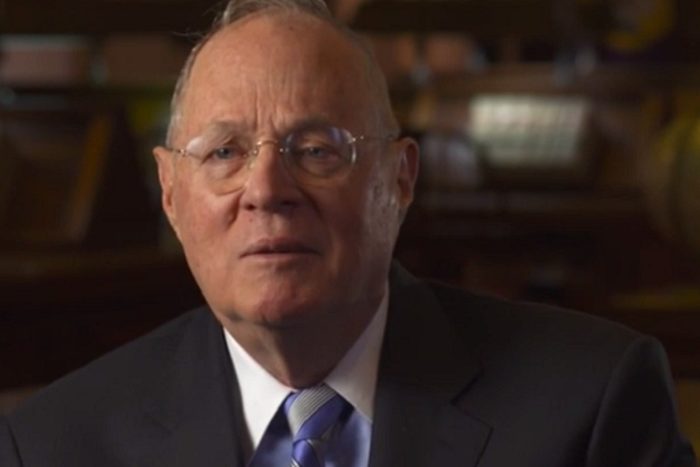

To trace the seismic shift that has produced the current climate of attack after attack on reproductive freedom, we should look not just to the loss of Justice O’Connor and the addition of Justice Alito, but also to the actions of Justice Anthony Kennedy. Under his guidance, the Court lurched abortion jurisprudence violently to the right—most notably in Gonzales, the first Supreme Court ruling on a pre-viability ban that contained no health exception for a pregnant person. Writing for the conservative majority in Gonzales, Justice Kennedy said that patients who needed an abortion later in their pregnancy would have other options, such as standard D and Es. Even though the Court had just reached the exact opposite conclusion as it had in Stenberg, Kennedy’s opinion suggested that the ruling in Gonzales was limited and posed no real long-term threat to abortion rights. Trust him.

Eight years later, so-called dismemberment bans that target D and E procedures—by far the most common method of second-trimester abortions—have now passed in Kansas and Oklahoma. They are lurking in the background in legislatures in South Carolina and Missouri. These latest rounds of abortion restrictions seek to finish what anti-choice advocates started in Gonzales: the eradication of later abortion options for patients who need them. To do that, they’ve developed a legislative and litigation strategy that is a case study in how to undermine constitutional abortion protections and upend settled law.

And despite what Justice Kennedy may have claimed in Gonzales about leaving choices available for pregnant patients, there is nothing in the history of his abortion rights opinions that would suggest he is really interested, should these D and E restrictions go to the Supreme Court, in options other than birth.

Justice Kennedy was the only member of the current conservative wing of the court to vote to uphold abortion rights in Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992. This has led some people to regard him as a “moderate” or “swing vote” on these matters. Since then, however, he has yet to come across an abortion restriction he finds unconstitutional, and his opinions drip with paternalism and moral condemnation of a pregnant person in need of an abortion.

“The majority views the procedures from the perspective of the abortionist, rather than from the perspective of a society shocked when confronted with a new method of ending human life,” wrote Kennedy in his dissent in Stenberg v. Carhart. Nothing says “moderate” or “swing vote” on abortion like calling doctors abortionists, am I right? “States also have an interest in forbidding medical procedures which, in the State’s reasonable determination, might cause the medical profession or society as a whole to become insensitive, even disdainful, to life, including life in the human fetus,” he continued.

That’s not the kind of language reproductive rights advocates hope to hear from a Supreme Court justice contemplating the interests of pregnant people to be free from state-coerced birth. Nor is it the kind of language medical professionals hoping to practice medicine free from judicial micromanagement want to hear, either.

Not surprisingly, Kennedy’s dissent gets worse. “Those who oppose abortion would agree, indeed would insist, that both [intact and non-intact D and E] procedures are subject to the most severe moral condemnation, condemnation reserved for the most repulsive human conduct.”

In other words, Justice Kennedy is here to save the medical profession from itself and to protect hapless pregnant people from the consequences of their own actions.

But it’s not just Kennedy’s language in Stenberg that is problematic. It’s his equating the state passing a moral judgment against abortion to the power of the state to regulate abortion pre-viability. In Kennedy’s view, the state has apparently endless constitutional power to regulate abortion, even banning procedures that happen pre-viability despite the fact that from Roe v. Wade on the Court has consistently held that states may not do so.

In the Stenberg dissent, such rhetoric is harmless, because dissents have no legal, binding value as precedent. They can be the equivalent of a justice shaking his fist at the sky and yelling. But when the ideas in that dissent later become those in the majority opinion, like it did in Gonzales, the effect on pregnant people and their constitutional rights is devastating.

Justice Kennedy returned to his disturbing language about D and E procedures—the ones very commonly used in second-trimester abortions—in the Gonzales majority opinion, writing, “No one would dispute that, for many, D and E is a procedure itself laden with the power to devalue human life.”

And under Justice Kennedy’s guidance, the Court finally was able in Gonzales to reframe the abortion debate where the interests of the state can outweigh the interests of the pregnant person before fetal viability, allowing the government to regulate abortion in that time period. Kennedy wrote, “Congress could nonetheless conclude that the type of abortion proscribed by the [Partial Birth Abortion Act] requires specific regulation because it implicates additional ethical and moral concerns that justify a special prohibition.”

And anti-choicers have followed in those state-interest footsteps.

In the initial rounds of reaction to the D and E bans passed by Kansas and Oklahoma reproductive rights supporters quickly, and rightly, noted that unlike the previous “partial-birth abortion” bans, these latest restrictions were even broader in scope. This should suggest that despite the clear anti-abortion bias among the conservative majority, the Roberts Court would decline to uphold these restrictions. Plus, amid all his talk of D and Es devaluing human life, Kennedy had explicitly pointed out non-intact dilation and evacuation abortions as an option for women in Gonzales, right?

I wish I could say I shared that faith that the Court will do the right thing. But given the Court’s track record, I just don’t. Look at what happened with last summer in Hobby Lobby, for example: The conservatives, including Justice Kennedy, allowed for-profit corporations a religious exemption from complying with the birth control benefit in the Affordable Care Act, because such an exemption existed for nonprofit businesses. That exemption, the conservative majority in Hobby Lobby ruled, proved there were other, less burdensome ways for the Obama administration to meet its goal of eradicating gender discrimination in insurance coverage. The very next day, the Court then tried to chip even further at birth control availability in Wheaton College, when it ruled the nonprofit’s religious rights were likely violated by the accommodation process whose constitutionality it had just affirmed. Justice Kennedy, in particular, had relied on the existence of the nonprofit accommodation in Hobby Lobby as an example of how the government could get it right when balancing gender equality and religious objections to contraception. Then he’d joined with conservatives in blocking that same accommodation the very next day.

This suggests Kennedy plays a long game. In the case of the contraception benefit, it was by holding up the nonprofit exemption as an option, then working to take that option away.

The same can be said for D and E bans. Despite trying to assure folks that the reach of Gonzales was limited, the language and the effect of Kennedy’s decision shows that was never the case. He showed his hand first in Stenberg by fully embracing anti-choice language and rhetoric decrying “abortionists,” and elevating the interests of the state above those of the pregnant person. Then he played it masterfully in Gonzales by setting out all the reasons why the ruling should apply to all D and Es, before reigning the opinion in with his conclusion: that the federal law only regulated a fraction of the procedures. There’s no reason to think he won’t continue his pattern with the current D and E bans.

If there’s good news here, it’s that it will take a while before the issue reaches the Roberts Court, which conceivably could also mean a different makeup of the Supreme Court, depending on retirements and future presidential appointments. So far only two states have passed D and E bans, and while no legal challenges have been filed yet, it’s reasonable to think they are coming. But it’s also clear anti-abortion advocates hope those challenges do come. States like Kansas and Oklahoma don’t just provide the anti-choice side with friendly state legislatures to pass what should be considered blatantly unconstitutional abortion restrictions. These states are also situated in conservative federal court jurisdictions that are extremely hostile to abortion rights, and thus likely to uphold them.

The same is not true for anti-abortion states like Ohio, Indiana, and Arizona, where anti-abortion restrictions have, for the most part, faced tougher scrutiny in the federal courts. Somewhat counterintuitively, my educated guess is that we’ll see similar bans pop up in those states, as anti-choicers hope to force a split among the federal courts on the constitutionality of these restrictions. Such a split would require the Roberts Court to step in. By the looks of things today, that has been the anti-choice plan since the ink first dried in 2007 in Gonzales.