These Black Men Pushed Abortion Access Before ‘Roe’

Black male judges such as Thurgood Marshall, state legislators, and physicians paved the way for legalized abortion, argued that the poor were hardest hit by restrictions, and made sure that women could get this essential care.

Many who celebrated the success of the recent worldwide Women’s Marches—record-breaking numbers, wonderful esprit, and their peacefulness—were also gratified by the significant participation of men in the women-led events. This widely noted involvement of men in the marches prompted me to think of another important example of men supporting the aspirations of women, but one less noted today: the role of Black men in the struggle for abortion rights before Roe v. Wade legalized abortion nationwide. These men played crucial roles in key legal cases, introduced pioneering pro-choice legislation, and as doctors, made sure women could get this essential care.

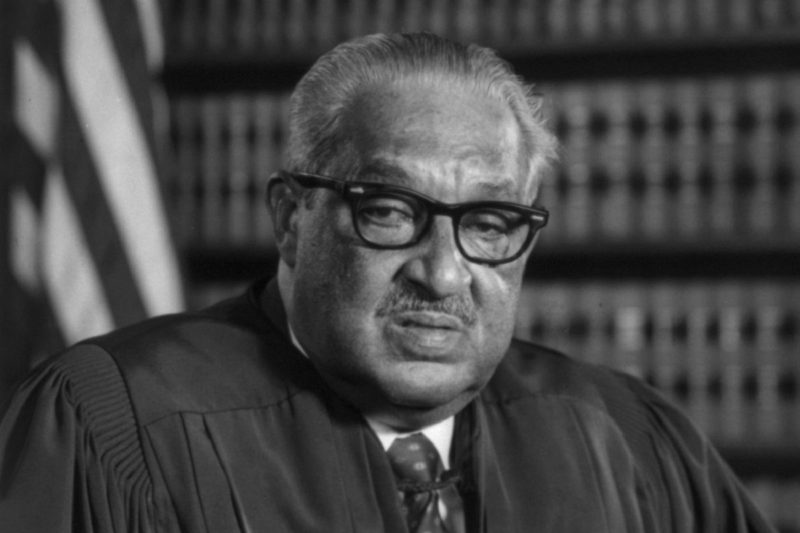

Consider the case of Thurgood Marshall, the first Black person appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court. He was a towering figure in the civil rights movement. As a lawyer for the NAACP, he successfully argued the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed school segregation in the United States, and he argued a host of other key civil rights cases throughout his career. But while celebrated for his role in civil rights law on and off the nation’s highest court, Marshall arguably has not been adequately recognized for his progressive and influential role in crafting the Roe v. Wade decision.

As the journalist Juan Williams wrote in his 1998 biography of Marshall, the Supreme Court justice was very sympathetic to abortion rights, based on his awareness of the numerous impoverished Black women who died or who were injured at the hands of inept illegal abortion providers. Williams argues that Marshall saw legal abortion as a matter of social justice, since rich women could get around laws against abortion and obtain the procedure safely (leaving the country, if necessary) while poor women could not.

The most interesting revelation from Williams’ account was Marshall’s role in pushing Justice Harry Blackmun, the author of the majority opinion in Roe, in a more liberal direction with respect to the permissible time frame of legal abortion. As Williams writes:

Marshall was openly aggressive in trying to shape Blackmun’s opinion. The initial draft limited abortions to the first three months of a pregnancy. Justice [William] Brennan, however proposed that the three-month limit be replaced with a new standard—when a fetus was “viable” outside the mother’s body …. Marshall sent a memo to Blackmun in support of Brennan’s idea. “Given the difficulties which many women may have in believing that they are pregnant and in deciding to seek an abortion, I fear that the earlier date may not in practice serve the interests of these women.”

In 1977, when the Maher v. Roe case about the constitutionality of using Medicaid to fund abortions came before the Court, Marshall again spoke on behalf of the poorest women in society—albeit unsuccessfully, as his side lost 6 to 3. In an unusually harsh dissent, Marshall wrote: “The enactments challenged here brutally coerce poor women to bear children whom society will scorn every day of their lives …. I am appalled at the ethical bankruptcy of those who preach a ‘right to life’ that means, under present social policies, a bare existence in utter misery for so many poor women and their children.”

Marshall was only one of a number of Black men to advocate for the legalization of abortion. As the sociologist Nicola Beisel has pointed out, in the years leading up to Roe, “Black politicians (nearly all of them men) introduced legislation to repeal or reform state abortion laws in New York, Illinois, Oklahoma, Michigan, Tennessee and Wisconsin. These men, acted, in part, because of the suffering illegal abortion disproportionately inflicted on Black women.”

Indeed, the first bill in any state legislature to propose repealing a state abortion law was introduced by Lloyd Barbee, a Black legislator in Wisconsin. Similar to Justice Marshall, whose strenuous legal advocacy for abortion is largely unremarked upon, Barbee is not known today for his pioneering work on that issue but rather for his leadership in the fight to desegregate Milwaukee’s schools.

Black doctors also played a significant role in safe abortion provision before Roe v. Wade. One of the most important of these was a Chicago physician, T.R.M. Howard, who worked with the Clergy Consultation Service network of religious leaders who referred women for safe abortions before Roe. Howard later transitioned to providing legal abortions immediately after the decision in 1973.

That March, just months after Roe was announced, Dr. Howard appeared on the cover of Jet magazine, one of the most popular publications in Black communities. In an effort to convey the medical legitimacy of the newly legalized procedure, he was portrayed performing an abortion in a spotless clinic. As the historian and Rewire editor Cynthia Greenlee wrote, Howard was also a very active civil rights leader both in Chicago and in the South: He led efforts calling for a thorough investigation into the murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black youth who was kidnapped and murdered by a white mob in Mississippi in 1955 after false allegations of “sexual crudeness” toward a white woman (allegations only recently recanted after some 60 years).

But today Howard is little remembered for either his civil rights activity or his abortion work. As Greenlee wrote, “Howard is one of the most significant civil rights leaders to fly under the history radar.” But in reminding us of the doctor’s legacy, she aptly argued, “Howard didn’t just belong to the civil rights movement. Like Black physicians and midwives before him, he belonged also to the abortion rights movement. In his inimitable and controversial way, Howard pointed out in Jet that abortion could be safe, legal, and even convenient.”

As I have noted in my own work on abortion provision before legalization, Detroit’s Edgar Keemer was another Black doctor who was very active as an abortion provider in the pre-Roe era. He was also a prominent member of the socialist and civil rights movements of his day, and was outspoken about the higher death and injury rates that Black women suffered from incompetently performed illegal abortions. Keemer was convicted and jailed for a brief period in the 1950s for performing an illegal abortion, but after his release he continued this activity, and like Dr. Howard, worked closely with the Clergy Consultation Service.

None of the men in this piece ever used the term “intersectionality,” a term coined years after the events mentioned here. Yet each man demonstrated by his actions that he had a visceral sense of the connection between the situations of the most vulnerable women in the United States and the need for reproductive justice—another term created after their work, but, clearly, one that they intuitively understood.