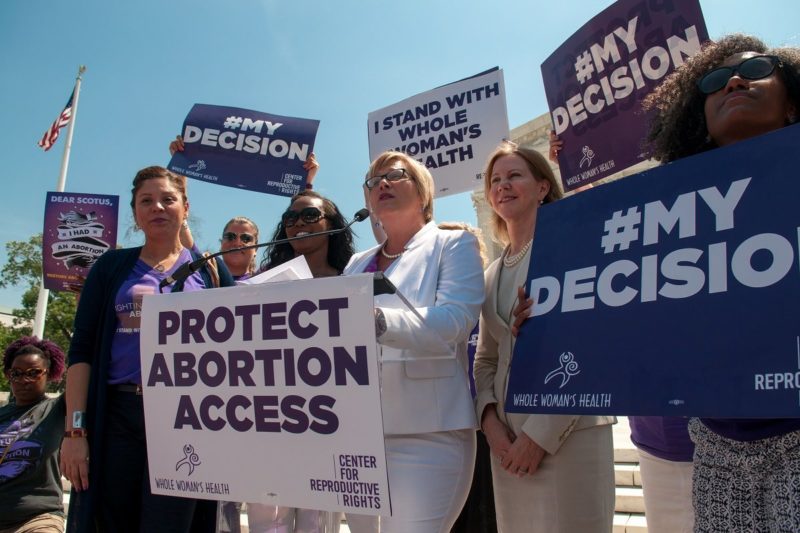

Can ‘Whole Woman’s Health’ Help Push Back Attacks on Voting Rights?

In a series of cases tackling the issue of racial gerrymandering before the Roberts Court Monday, the possibility of abortion rights jurisprudence protecting voting rights started to emerge.

This summer’s win in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt was an affirmation of the fundamental constitutional right to an abortion. However, it was also an affirmation of the responsibility of the courts to review both data and legislative intent in claims of constitutional violations. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court considered again the role courts have in weighing evidence and second-guessing lawmakers—only this time in the context of two cases of racially gerrymandering congressional districts, Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections and McCrory v. North Carolina.

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) dictates that those states it covers may consider race in drawing legislative districts so that voters of color who have historically been cut out of the electoral process are fairly represented in state and federal office. At the same time, the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution prohibits lawmakers from considering race too much when crafting legislative districts. If that balance is off, those districts are considered unconstitutionally racially gerrymandered.

Monday’s arguments made it clear that determining when lawmakers have unconstitutionally used race as a predominant factor in redistricting and when they did not is a murky exercise for the courts.

Bethune-Hill and McCrory arose from legislative redistricting following the 2010 Census, when both North Carolina and Virginia redrew their congressional districts. The VRA says that those states with a history of racial discrimination in voting must meet certain criteria to show they are no longer discriminating on the basis of race. One way the law seeks to do that is by requiring covered states to consider race when redistricting. In theory, this will guarantee that voters of color have the ability to elect representatives of their choice.

The question for the courts is when have states engaged in improperly “packing” legislative districts on the basis of race, either by creating artificially “racially concentrated” legislative districts or by spreading voters of color out throughout many neighboring districts.

North Carolina and Virginia argue they did not improperly pack voters of color into specific districts, and that the manner in which race factored into their 2010 redistricting was actually necessary to comply with the VRA’s directive that voters of color in covered states have a way to preserve their ability to elect candidates of their choice. Opponents claim what lawmakers are really doing is using compliance with the VRA as a disguised way to reduce voting power of those people of color. They argue lawmakers are drawing legislative districts so those voters are spread across many districts, but not so thinly as to make the dilution of their vote on the basis of race obvious.

It gets a little more complicated too. While the use of race in drawing legislative districts is subject to a very high level of constitutional scrutiny, political motivation in doing so is not. States can legally draw districts with political motivation—as in, to maximize partisan strength, as Republicans have done very successfully since 2010. But they have to be very careful about how they use those considerations. That creates the possibility that lawmakers can say it’s political motivation for drawing legislative districts, when in reality, it was race.

The legislative presumption in these redistricting decisions like the ones before the Court Monday is that race correlates strongly with political affiliation, and that more nonwhite voters cast ballots for Democrats than Republicans. In other words, because at the moment race and political affiliation strongly correlate, lawmakers can claim they are simply redistricting with an eye to political advantage, when what they are really trying to do is disenfranchise voters of color by manipulating the legislative maps.

Monday’s argument sought to find some clarity on when redistricting efforts are unlawfully racially motivated or when they are just a function of partisan politics. But while the issues before the Court centered on race and politics, the attorneys and the justices spent the bulk of arguments debating what, if any, evidence challengers need to provide to show a legislative district was drawn using improper racial motivations rather than political motivations. Veteran Supreme Court litigator for conservative causes Paul Clement pressed the Court to accept his clients’ position that when a lawmaker says politics—and not race—was the motivating factor in a redistricting decision, the courts should have very little room to second-guess that reasoning.

This is, of course, the same argument Clement made in Whole Woman’s Health, when lawmakers in Texas insisted the abortion restrictions passed—which decimated abortion access in the state by prompting a tidal wave of clinic closures—were in fact done to advance patient health and safety. In rejecting that claim this summer, the liberal wing of the Court made it very clear that lawmakers’ intent when legislating on issues involving fundamental constitutional rights is absolutely up for review.

So it was not a surprise Monday to hear Justice Stephen Breyer, the author of the Whole Woman’s Health decision and the Court’s resident data nerd, pressing Clement on the role of the courts in racial gerrymandering cases. And it was even less of a surprise to hear Justice Elena Kagan—perhaps the Court’s most knowledgable justice on election law—joining Breyer on the offense.

“[L]awmakers will say one thing and mean another,” Kagan flatly told Clement. In other words, Kagan said, “the justification [for drawing a particular legislative a certain way] is politics, but the true reason is race.”

While Breyer and Kagan were the most vocally skeptical of Clement’s arguments, Justice Samuel Alito was the quickest to defend lawmakers’ motivations. It is no secret the conservatives on the Court do not like the Voting Rights Act. Chief Justice Roberts and his conservative colleagues did all they could in 2013 to gut it in Shelby County v. Holder, and given the line of questioning by Justice Alito, it’s clear if given the opportunity to rule the entire law unconstitutional, the conservatives on the Court would do just that. In these cases, they can strike another mortal wound to the law by granting lawmakers cover to improperly racially gerrymander legislative districts in their states and claim their actions were just politics as usual.

Given its current makeup, however, the only way the Roberts Court can do real and sustained damage to the VRA like they did in Shelby County is to get a five-member majority. That means once again, Justice Anthony Kennedy is the justice to pay attention to.

It’s fair to say Justice Kennedy has sent some mixed signals on race and constitutional law. He’s clearly uncomfortable with anything he believes as advancing racial “quotas,” as evidenced in his opinions in the affirmative action cases to come before the Court. He also sided with his conservative colleagues in Shelby County to gut the VRA, signing onto Chief Justice John Roberts’ holding that this country is “post-racial” and civil rights era laws like the VRA do more to enshrine racial discrimination than upend it. But more recently, Kennedy defended voters of color in Alabama who argued their state’s legislative districts were improperly racially gerrymandered. So on the one hand, it is difficult to picture Kennedy signing on with his conservative colleagues to any opinion that would give lawmakers a green light to claim they are using political considerations, rather than improper racial ones, in drawing legislative districts. On the other, we have Kennedy’s vote in Shelby County.

Overall, the political and practical constraints facing the Court may be good news in the short term in that they make a big opinion really doing harm to the VRA difficult to craft, but that is little comfort looking ahead. North Carolina is tied up in additional litigation around its redistricting efforts from 2010. That case involves the racial gerrymandering of state legislative districts, not just congressional ones. A federal court last week ordered lawmakers to redraw those districts by March. Republicans have already appealed that order as well, making it likely North Carolina’s redistricting problems will remain before the Court for at least another year.

During that time, unless Democrats show uncharacteristic unity and strength in opposing any Trump Supreme Court appointment, the Roberts Court will eventually get its ninth justice. And it is likely that justice will be as hostile to voting rights as the rest of the conservatives on the Court. So while Monday’s cases may not produce a sweeping win for either side, the issue of how and when lawmakers can use race in drawing congressional districts isn’t going away anytime soon.

If the prospect of the Court revisiting the issue in later terms sends a chill down your spine, now would be a good time to reread Justice Breyer’s majority opinion in Whole Woman’s Health. In that opinion, he methodically lays forth the duty of the courts to question lawmakers and the evidence they use in support of restricting fundamental constitutional rights. And while Whole Woman’s Health isn’t a voting rights case, the decision has value as legal precedent and offers an analytical model for advocates to use challenging restrictions on other constitutional rights. In fact, it has already been cited in at least one voting rights case.

We may not see proof of that in this term with these cases, but we very well could in the next series of voting rights challenges to land before the Court. The question, then, for the conservative justices won’t be how much deference to pay lawmakers, but instead how much they must pay to the Court’s own precedent.