Books, Blunts, and Bullets: On Black Men Reading, Loving, and Dying

I had thought that as a "good" progressive and a "woke" Black person, I could see Keith Lamont Scott's complexity without blinders and bias. But what I realize now is that state violence goes so deep, it may take my lifetime—and certainly longer than Scott's—to excavate it.

Of all the details to emerge about the September 20 police shooting of 43-year-old Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte, North Carolina, there is one that haunts me.

Right before his death, Scott may have been reading a book.

I fixated on this claim, maybe because Scott was a fellow North Carolinian. Or maybe it was a mental detour that helped me skirt the psychic grimness of now, when Black lives are as cheap as paperback novels and the people who take them are as unapologetically unashamed as some presidential candidates.

I obsessively wondered what that book may have been. Was he a devotee of true crime novels? Perhaps he preferred science fiction. Was the car the only place where he, a father of seven, could steal a few moments of companionable solitude with a book? And, if as his mother suggested, Scott loved the Koran more than any other book, was his copy as dog-eared and beloved as Korans everywhere? What was the last sura that his eyes scanned?

His family claims that he was doing as he often did: poring over a book while waiting for his son’s school bus.

Officials with the Charlotte-Mecklenburg County Police Department have a different version of events, saying that he brandished a gun—a still-contested claim—or had marijuana in the parked car, which caught the surveilling eye of authorities when they were looking for an entirely different man.

As with any police killing, the “facts” and narratives will change countless times, especially with the predictable recriminations that the dead Black person was a criminal or unsavory type. And, yes, it took little time and a few public records searches to find Keith Lamont Scott had done time in jail and had been accused of threatening his family with a gun a year before he was shot down by police.

These reports brought me up short and interrupted my internal narrative. When I started writing this piece, I had planned to connect Scott’s automotive reading to my father’s capacious book-love. It was my father who spent the equivalent of several months’ mortgage payments buying his three daughters an expensive encyclopedia set. He never failed to renew my annual Christmas subscription to National Geographic, and he conveniently ignored the many times I forgot to take out the trash because I was reading (though he eventually began subtracting substantial sums from my allowance for every incomplete or tardy chore). In this story, Keith Lamont Scott was like my father: a family man and Man of the Book, in the most literal sense.

And he was a little like me in that, apparently, he couldn’t bear to be without a book.

This piece was to be an ode to Bookish Black Men.

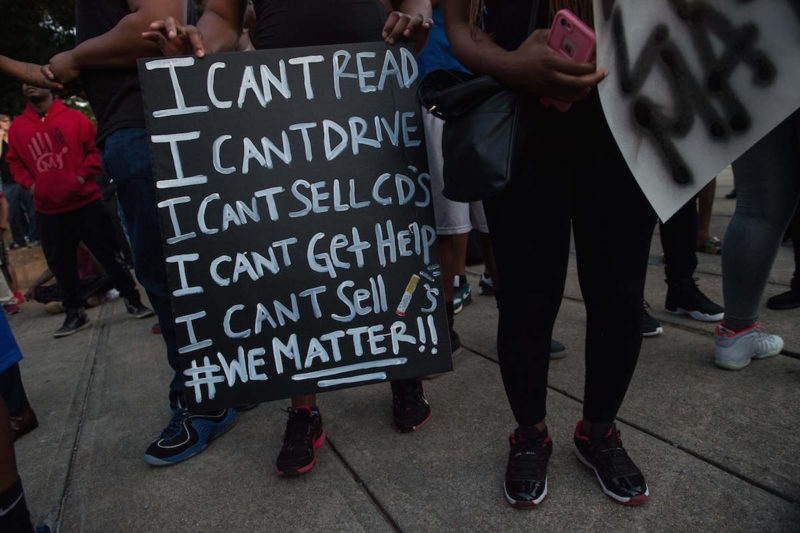

Keith Lamont Scott’s story—or the initial version of that story—captured my attention because I know many Black men who give their children money for school book fairs and who love the Word, whatever their religion. And it toppled ugly stereotypes that Black men can’t be and aren’t caring fathers and Men of the Book. Because according to conventional wisdom, Black men don’t consume books. They consume women; expensive sneakers; rap music; and copious amounts of malt liquor, Cristal, and gin and juice. They chew up and spit out peace on the streets of this country.

But shortly after I began writing, I stopped. I couldn’t pick it up for days. I struggled reconciling that initial vision of a Black father reading in his car with the Keith Lamont Scott on the news, the murdered-man-now-hashtag whom Charlotte law enforcement says was rolling a blunt and carrying a stolen gun in a car that would soon carry his child.

How easily I succumbed to the idea of worthy victims and the strategic, racist suggestions that Black people and the brutalized invite fatal punishment.

Even when I know that marijuana possession is not a capital crime and does not ever justify summary execution on an almost-fall day.

Even as I know that serving time in jail shouldn’t brand you forever and that people with disabilities like Scott, who had a traumatic brain injury, die at the hands of police in alarming numbers.

Even as I know that my state—North Carolina—is an open-carry state, where you can have a gun in your car with no special license; you can bring your weapon into restaurants, bars, or Grandma’s funeral, thanks to the infinite ignorance of the same legislature that brought us the horrible and expensive folly of the transphobic HB 2 law.

Somewhere along the way, I had internalized the idea that blameless Black men—those who wear their literacy on their sleeves and carry books, not firearms—deserve our mourning. And it was a shocking self-realization that I divided people into these facile and fictitious categories: those who carry books equal good, and those who carry guns equal reprehensible and disposable.

My father, the bibliophile whose bookshelves have always been filled with James Baldwin and the works of Black sociologists, is also a gun owner who advocated gun ownership for Black people. He taught my 9- and 10-year-old sisters how to shoot in our backyard when neo-Nazis massacred peaceful protesters in our city, Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1979. And he gave me a tiny, “ladylike” pistol as a housewarming gift for my first apartment, along with a machete and a Taser.

My father’s hands held both books and guns, and I can see his complexity. I had thought that as a “good” progressive and a “woke” Black person, I could see Keith Lamont Scott’s complexity without blinders and bias. But no matter what Scott carried—a blunt, a book, a gun, or a police record—his death showed me what I and many Americans still carry: the idea that you can behave your way into safety and an acceptance. But what I realize now is that state violence goes so deep, it may take my lifetime—and certainly longer than Scott’s—to excavate it.