The Hyde Amendment and Beyond: The Conservative Attack on Reproductive Health Care That Just Won’t Quit

Almost 40 years since the Hyde Amendment was first passed, another Supreme Court fight over reproductive health-care access and income inequality is shaping up.

This week marks the 39th anniversary of the Hyde Amendment, the federal appropriations ban on Medicaid reimbursement for most abortions. This summer will also mark the 35th anniversary of Harris v. McRae, the Supreme Court decision that ruled the Hyde Amendment’s restrictions constitutional, enshrining into law the idea that it is completely permissible for Congress to discriminate against poor people when it comes to reproductive health-care access.

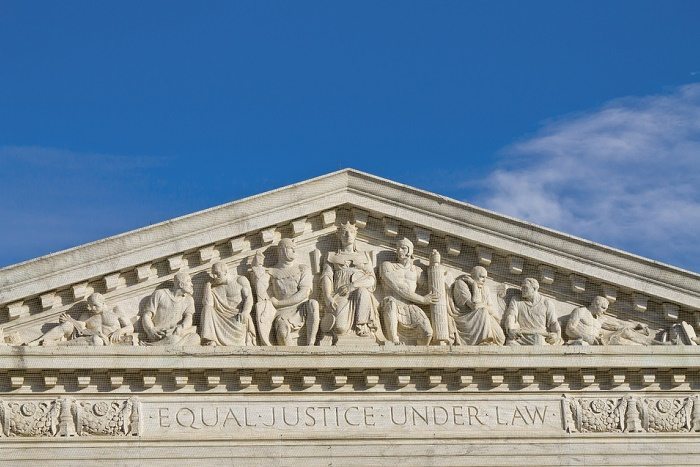

The Hyde Amendment singles out low-income people for unequal treatment under the law. In order to come to the conclusion that it is constitutional, conservatives on the Supreme Court in 1980 advanced what has become a familiar mantra in opposition to reproductive rights: Just because a federal right to abortion exists doesn’t mean the government is obligated to pay for it. It’s a catchy quip, and one that persists today. But it is also an inherently dishonest way to think of how our fundamental rights work—one that depends on ignoring the realities of structural inequality.

“The Hyde Amendment,” wrote the Court in Harris v. McRae, “places no governmental obstacle in the path of a woman who chooses to terminate her pregnancy, but rather, by means of unequal subsidization of abortion and other medical services, encourages alternative activity deemed in the public interest.”

Under the Medicaid program, which currently provides coverage for approximately 60 million individuals, federal and state governments jointly pay for the health-care services of eligible low-income individuals and their families. Medicaid funding provides coverage for the “categorically needy” with respect to five general areas of medical treatment, including “skilled nursing facilities services, periodic screening and diagnosis of children, and family planning services.”

In theory, that “family planning services” coverage should extend to abortion care. But it doesn’t, thanks to congressional Republicans. First passed in 1976—just three years after Roe v. Wade said the right to an abortion is fundamental—the Hyde Amendment, named after Rep. Henry Hyde (R-IL), places various limits on Medicaid funding for abortions. Currently, it only provides funding for abortions in cases of rape, incest, or life endangerment of the pregnant person. The Hyde Amendment is not permanent law. Rather, it is a funding limitation created by Congress, one legislators must renew every year.

Today approximately one in ten women are Medicaid enrollees, with women comprising more than two-thirds of adult rolls. According to a 2009 Kaiser Family Foundation report, Medicaid pays for more than four in ten births nationwide; in some states, it pays for more than half of the total births. With no Medicaid assistance for abortions, poor patients often have to reschedule appointments while they try and save money to pay for them, which pushes them into later, more expensive and potentially riskier abortions. Or worse, it forces them to carry to term pregnancies they otherwise would not.

Yet according to the Supreme Court in Harris v. McRae, the Hyde Amendment is not a government-created obstacle designed to limit access to the fundamental right to an abortion. It is rather just an exercise of state power, one that encourages childbirth over abortion.

No, I can’t explain the legal difference between those two positions, because there is none. Harris v. McRae is a case study in conservative morality policing, a truth borne out later in the opinion. Let’s walk through it.

“[A]lthough government may not place obstacles in the path of a woman’s exercise of her freedom of choice, it need not remove those not of its own creation,” the Court in Harris wrote. “Indigency falls in the latter category. The financial constraints that restrict an indigent woman’s ability to enjoy the full range of constitutionally protected freedom of choice are the product not of governmental restrictions on access to abortions, but rather of her indigency.”

In other words, it is not the Hyde Amendment preventing poor patients from accessing abortion care; it’s the fact that they are poor to begin with.

“Whether freedom of choice that is constitutionally protected warrants federal subsidization is a question for Congress to answer,” wrote the Harris Court. “[I]t simply does not follow that a woman’s freedom of choice carries with it a constitutional entitlement to the financial resources to avail herself of the full range of protected choices.”

So. The Supreme Court in Harris v. McRae said that the congressionally created Hyde Amendment was not a government-created obstacle designed to limit poor patients’ reproductive health-care choices. Those choices, the Court reasoned, are already limited by the fact that the patient is poor and all the Hyde Amendment does is express the government’s general preference for childbirth over abortion. Somehow, it does not place another obstacle on the indigent person’s path to try and terminate a pregnancy.

OK then.

Almost 40 years and as many renewals of the Hyde Amendment later, conservative gamesplaying with Medicaid family provisions have only amplified. As their party heads to the 2016 presidential elections, Republicans are now calling for Benghazi-like investigations into Planned Parenthood and to exclude the reproductive health-care provider from the Medicaid program.

It’s important to note that conservatives in states like Indiana and Tennessee quietly widened Medicaid eligibility while continuing to pursue ways to strip comprehensive reproductive health-care services from its list of covered items. These states expanded their Medicaid programs because, frankly, they work. Medicaid as a venture of cooperative federalism has been a smashing success in reducing barriers to health care. Which is what makes the injustice of singling out abortion as the only medical procedure excluded for Medicaid funding all the more apparent.

“When viewed in the context of the Medicaid program to which it is appended, it is obvious that the Hyde Amendment is nothing less than an attempt by Congress to circumvent the dictates of the Constitution and achieve indirectly what Roe v. Wade said it could not do directly,” Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. wrote in his dissent in Harris.

And as we’ve seen in the last five years with the unprecedented explosion of reproductive rights restrictions at the state level, conservatives never planned to end their campaign with undoing abortion rights. Upending contraception access, a cornerstone of science- and evidence-based family planning services, is also part of the right’s political play—especially where low-income people are concerned.

HR 3495, which the House votes on this week, would allow states to exclude providers from Medicaid based on ideology like a moral or religious objection to contraception and abortion, or a declaration that a fertilized egg is a person. HR 3495 builds off conservatives’ win in Hobby Lobby, the case last summer that allowed for-profit secular employers to raise religious objections to providing employee health insurance plans that covered contraception as required under the Affordable Care Act. So those who “consciously object” to providers who perform abortions are perfectly poised for support among the conservatives on the Roberts Court—most notably Justice Kennedy, who has yet to vote to support reproductive rights since 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

If enacted and supported, HR 3495 could mean the end of reproductive health care grounded in science. But only for poor women.

So far, thanks to the Roberts Court, conservatives have successfully rolled back insurance coverage for contraception under the Affordable Care Act. HR 3495, by granting states the power to discriminate against health-care providers based on ideology, could do to contraceptive services under Medicaid what Hobby Lobby did for contraception coverage in the private sector: subject the right to access it to conservative veto. And with the holding and reasoning from Harris to guide them, there’s every reason to think the Roberts Court would find that restriction constitutional.

In addition, it’s very likely the Roberts Court will hear an abortion case and a contraception case this term. These cases, to varying degrees, address issues of reproductive health-care access and income inequality. That means the themes of state power, individual rights, and just how far the government can go to obstruct a patient from terminating a pregnancy—or accessing reproductive health care generally—will again be at the forefront of our legal conversations. And it will happen against the backdrop of the 2016 presidential elections and the Planned Parenthood smear campaign. It’s hard to see these converging events as a good thing.

All this means we shouldn’t just be outraged at the injustice of the Hyde Amendment on its anniversary; we should be scared of what follows.