How Louisiana Slashed Medicaid Funding for Pregnant Women and Blamed a Typo

Louisiana health officials appear to have cut funding for the state’s Medicaid program for pregnant women based on a typo on the Affordable Care Act website, Healthcare.gov.

Over the last several months, the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals made a series of announcements about LaMOMS, the state’s Medicaid program for pregnant women—first announcing cuts to the program, then a plan to reevaluate those cuts, and then that the cuts were being rescinded. Health Secretary Kathy Kliebert explained in a series of interviews with the Baton Rouge Advocate that this seesaw of decisions was caused by an unspecified change in federal policy related to the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

The $11 million in cuts, which passed as part of the 2013-2014 state budget in June, were added back into the budget in November. But the reversal dictated that the category of women who were slated to be dropped from LaMOMS are now instead covered through the state’s Medicaid program for children, LaCHIP. This means that the Medicaid funds are now technically for “unborn children,” not for the pregnant women themselves, and these women will lose postpartum care coverage. These changes went into effect in January.

Rewire spoke with the Louisiana health department and ACA policy experts for clarification on why an ACA policy affected Louisiana’s longstanding LaMOMS program. A closer look reveals an odd story wherein officials planned to cut the LaMOMS budget by taking advantage of an ACA loophole—a loophole that, it turns out, did not exist. Rather, state health officials appear to have changed the state’s Medicaid funding of pregnant women based on a typo on the ACA website, Healthcare.gov.

When Louisiana officials discovered their mistake, they blamed the mixup on the Federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the department that oversees ACA implementation.

The saga represents a troubling example of the anti-ACA, anti-women maneuverings of the administration of Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal.

The Federal Policy Change That Wasn’t

The initial Medicaid cuts that passed in Louisiana’s 2013-2014 state budget established new income eligibility requirements that drastically reduced the number of pregnant women eligible for Medicaid in Louisiana. Previously, women earning up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL)—or up to $22,980 annually—were eligible for prenatal, childbirth, and 60 days of postpartum care through LaMOMS. But the reductions were slated to reduce eligibility to 133 percent, creating a new gap in coverage for women earning between $15,280 and $22,980.

Federal law requires that all states provide Medicaid to pregnant women, with an eligibility cap of at least 133 percent. The vast majority of states opt for much higher thresholds, as high as 380 percent.

“Eligibility is higher for pregnancy because we consider this to be a particularly important time period for health outcomes,” Laura Gaydos, assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at Emory University, told Rewire. “This is something that pretty much everyone agrees about.”

The reason Louisiana’s health department provided for the LaMOMS reduction was that women in the 133 to 200 percent FPL range are now eligible for subsidies on the federal health marketplaces under the ACA (which provide subsidies to individuals earning between 100 and 400 percent the FPL). In other words, the state didn’t want to continue funding Medicaid for women who might also be eligible for ACA subsidies.

Jan Moller, director of the Louisiana Budget Project, a nonprofit that monitors government spending, told Rewire that prenatal care “has been a huge priority for this administration because Louisiana ranks very poorly with birth outcomes.” Moller’s understanding of the cuts was that Louisiana officials believed women in the 133 to 200 percent range would sign up for private insurance on the ACA marketplace. “And of course, this was a way for the state to save money,” he added.

But there was a glaring problem with this strategy. What would happen if an uninsured woman didn’t enroll during ACA’s annual open enrollment period, and then became pregnant? She can’t sign up on the ACA, and she now no longer qualifies for Medicaid, which provides immediate access to no-cost care. Such a woman would be left with virtually no options for receiving care.

It turns out that Louisiana officials were operating under the false belief that becoming pregnant is a circumstance that triggers a “special enrollment period,” allowing women to sign up on the ACA marketplaces outside of the open enrollment period. When officials later realized this wasn’t the case, they reversed their Medicaid cuts, alleging that a change in federal policy had caused their confusion. As reported in an October Baton Rouge Advocate article titled “Rules Change Impacts Low-Income Pregnant Women”:

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has thrown the state a curve … a new interpretation of the term “qualifying life event” would leave some of those women in the gap without prenatal care, [health secretary] Kliebert said. The definition of a qualifying event to enroll in the new health insurance exchange outside of the open enrollment period removed the event of becoming pregnant.

“Federal policy messed us up,” Health Secretary Kliebert said in November, during her announcement that the previous Medicaid eligibility levels would be restored.

However, a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services spokesperson told Rewire that there had been no policy change.

In order to understand the issue at hand, it’s important to examine the concept of special enrollment periods, which are not unique to the ACA; anyone who has experience enrolling in private health insurance will be somewhat familiar. Specific events, such as losing a job, getting a new job, or gaining a dependent, trigger special enrollment periods that temporarily allow individuals or families to sign up for insurance outside of open enrollment periods.

For ACA insurance plans, pregnancy is not a qualifying life event. So Kliebert’s assertion that a new federal policy removed pregnancy from the list of such events is impossible: It couldn’t be removed from a list that it was never on. The rules for qualifying life events are available to the public and listed in subpart D of the Affordable Care Act.

“In no insurance situation that I’m aware of, whether in the ACA or outside of the ACA, is pregnancy a qualifying life event,” Professor Gaydos told Rewire.

Indeed, pregnancy as a qualifying life event runs counter to the fundamental logic of private insurance plans. Insurance companies don’t typically allow individuals to enroll upon changes in health status, such as becoming pregnant, because that would cause “adverse selection,” a concept predicting that costs throughout the market increase if individuals sign up for insurance only when they become sick. Medicaid access for uninsured pregnant women is thus a unique system allowing low-income, uninsured women to gain immediate coverage upon becoming pregnant.

“You would not have a special enrollment period for women who become pregnant,” said Judy Solomon, vice president for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “I don’t know what Louisiana could have meant when they thought pregnancy was included.”

The Culprit Behind the Confusion

Rewire contacted the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals for information about the federal policy change that led to it questioning the LaMOMS cuts. The department provided the following in an email statement from Secretary Kliebert:

The federal government’s website recently changed the definition of a qualifying life event to enroll in the new health insurance exchange outside of the open enrollment period, removing the event of “becoming pregnant,” … After seeking clarification, we’ve received multiple and conflicting answers … Our last communication with federal officials indicated that becoming pregnant will not trigger a special enrollment period for women.

A federal website hadn’t been mentioned in the Advocate articles, so this was a clue about the persistently vague references to a change in “federal policy.” The mystery was solved when a health department official told Rewire that the answer can be found in Kliebert’s September 2013 testimony before Congress regarding her department’s concerns about the ACA.

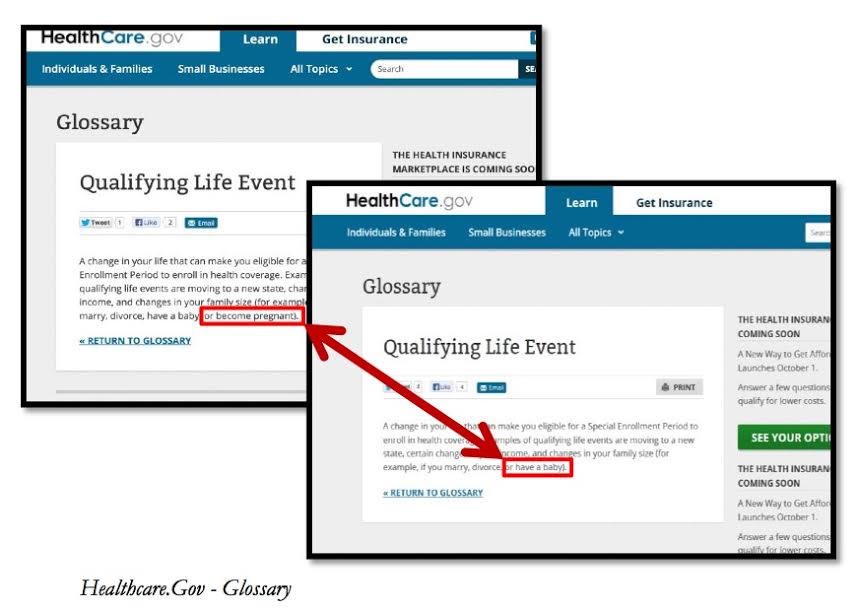

During her congressional testimony, Kliebert stated that “until very recently, HHS’s primary Exchange website, Healthcare.gov, had included in its definition of qualifying life event the example of when you ‘become pregnant.’ However, the information on the site recently changed to state that it is the birth of the baby that qualifies the woman for coverage.”

Kliebert included two screenshots that she said were taken “weeks apart” revealing photos of the same webpage, with one omitting “become pregnant” from the list of qualifying life events:

These screen shots aren’t dated, but it appears that for some unknown amount of time, this piece of misinformation was posted at Healthcare.gov. Kliebert’s testimony was in September, so it seems that this rather serious error was fixed prior to the website’s October 1 public launch.

In her anti-ACA testimony, Kliebert presented the Healthcare.gov error as an example of the difficulty her department experiences when communicating with federal officials. However, Kliebert did not mention that the glossary error had prompted Louisiana to revoke Medicaid coverage for low-income, uninsured pregnant women.

It’s unclear why Louisiana officials hadn’t consulted the rules of the ACA itself or contacted health-care experts before going ahead with the Medicaid cuts.

“A glossary is not a law,” said the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ Judy Solomon. “Pregnancy is not on the list. You can Google it.”

“It sounds like misinformation was presented [at Healthcare.gov], and then they did not go far enough in looking into the actual rule from CMS [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid],” said Professor Gaydos.

Yet, in lieu of admitting the mistake, Kliebert spoke to the press about an unnamed “federal policy” that “messed up” decisions surrounding the LaMOMS program.

Kliebert is an appointee and close ally of Republican Gov. Jindal, a vocal opponent of the ACA and the Medicaid expansion. In his Wall Street Journal op-ed about the health-care law, Jindal pinpointed the bureaucracy of state-federal interaction as the prime problem with the ACA:

Fifty-five working days before the launch of the ObamaCare health-insurance exchanges on Oct. 1, the administration published a 600-page final rule that employers, individuals and states are expected to follow in determining eligibility for millions of Americans. Rather than lending clarity to a troubled project, the guidelines only further complicated it. If the experience of those working with the ObamaCare implementation at the state level had been taken into account, progress might have been possible, but the administration has treated states with mistrust.

What’s so unsettling about the LaMOMS debacle is that Jindal’s administration was fast to cut LaMOMS funds in the dubious hope that women would instead receive subsidies on the very federal marketplaces that Jindal vehemently opposes. Jindal has deemed the ACA a “one-size-fits-all approach” that impedes a governor’s ability to “care for our most vulnerable citizens,” and yet was eager to siphon pregnant women into the ACA marketplace—and then blame the ACA when it didn’t work out, as if federal officials had forced the cuts onto LaMOMS in the first place.

The Jindal administration performed a similar about-face last summer. They quietly applied to participate in Community First Choice, a little-known ACA program that increases federal Medicaid funds for disabled and elderly care services. But then they withdrew the application, citing “new federal rules” and “complicated federal stipulations.” There is speculation that the real reason behind the withdrawal was presidential-hopeful Jindal’s reticence to be caught with his hand in ACA’s cookie jar.

The LaMOMS changes are part of a long list of Jindal administration cuts to health services for moms and children. In the 2012-13 budget, the state eliminated funds for dental services for pregnant women, an in-home nursing program to educate moms about infant care, and mental health services for low-income children. Further Medicaid cuts enacted this January included complete closure of the state’s Disability Medicaid program. Louisiana is thus not merely among the 25 states refusing to join the Medicaid expansion—it’s also cutting existing Medicaid programs, joining Wisconsin and Maine as the only three states to decline the expansion while at the same time dramatically reducing existing programs.

The Aftermath for Louisiana Women

Although the LaMOMS cuts were technically reversed, women will still be affected: Those in the 133 to 200 percent FPL range will now receive Medicaid through the state’s Medicaid fund for children, rather than through LaMOMS. Since the unborn fetuses will now be the ones receiving Medicaid, it’s unclear whether health services that don’t directly affect the fetus will be covered. Further, women will no longer receive the 60 days of postpartum care that is required through LaMOMS.

Louisiana has the second highest infant mortality rate in the nation, and infants born to mothers who do not receive prenatal care are five times more likely to die. In early November, when Louisiana’s health department was still considering whether to rescind the LaMOMS cuts, March of Dimes released new statistics on preterm birth, showing that Louisiana had improved very little despite pledges to address the problem.

“We urge policy-makers to expand insurance coverage, including Medicaid, for women of childbearing age,” the March of Dimes wrote on its “F” grade report card for Louisiana.

In the area of maternal health, Louisiana’s situation is so bad that the state was singled out for censure at last year’s UN General Assembly Millennium Development meeting on maternal health. The state has high rates of maternal death, too few practicing obstetricians, and a high proportion of uninsured women—27 percent of women of child-bearing age have no insurance, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Given these serious problems, it’s alarming that LaMOMS was ever considered a target for budget reductions.

Uninsured Louisianans in the 100 to 400 percent FPL range are indeed now eligible for ACA subsidies. But for those who don’t enroll in the ACA marketplace during open enrollment and then become pregnant, it’s important that Medicaid continue to provide these women with free, immediate care.

In most Republican-governed states, pregnant women are eligible for Medicaid only during their pregnancy, but are then dropped from the program. This is the case in Louisiana, which provides little Medicaid to non-disabled adults: Only adults with dependent children who earn up to $2,727 a year are eligible. This means that if a low-income woman earns more than $2,727, she loses her Medicaid coverage 60 days after giving birth, when LaMOMS coverage ends.

Some 242,000 Louisianans would gain insurance if the state participated in Medicaid expansion.

“What’s really unfortunate is you have a lot of very low-income women in Louisiana who have no opportunity to get [Medicaid] coverage until they are pregnant,” Solomon said. “These women need coverage.”