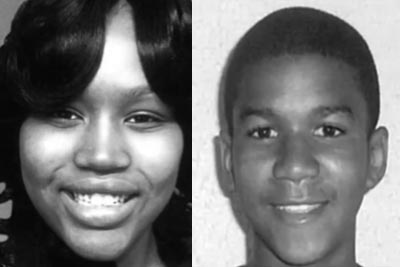

Where Is the Million Hoodie March for Renisha McBride?

McBride was killed in a manner more appropriate for a rabid animal trespassing on someone’s property than a human being with a full cadre of rights. Where is her mass protest?

It’s been two weeks since the unnecessary and untimely killing of Renisha McBride. On November 2, the unarmed 19-year-old who was in search for help after a car accident in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn Heights was shot in the face by Theodore Wafer, whose porch she had walked onto. The parallels between Trayvon Martin’s tragic killing and McBride’s are resonating in a national psyche rife with story after story of Black men and women gunned down as if their Black bodies have little or no value. And while we don’t know what will happen to Wafer as a result of the killing (George Zimmerman, the man who killed Martin, was acquitted) we know this pattern of violence must end.

Reports that have surfaced since the tragic killing note McBride was intoxicated at the time of the incident, implying that somehow she was responsible for her own death. McBride crashed into a parked car and walked a short distance to knock on Wafer’s door for help. Instead of, say, inviting her in to call 9-1-1 to report the car accident, he shot her in the face. Originally, Wafer claimed the shotgun fired accidentally, and he wasn’t arrested immediately after the shooting based on this version of events—reminiscent of the Zimmerman case.

Now that more evidence has surfaced, Wafer is claiming that he shot McBride in self-defense, even though the door to his home was locked and reports show that she was shot through this locked screen door and from a far enough distance that she didn’t pose an immediate threat. On Friday, Wafer was finally charged with second-degree murder and manslaughter and instructed to turn himself into the authorities. Wafer was arraigned, with his bail set at $250,000.

Beyond these facts, it appears McBride was killed in a manner more appropriate for a rabid animal trespassing on someone’s property than a human being with a full cadre of rights. Her life, like so many others in the Black community, was ended prematurely, for inexplicable reasons that defy logic about self-defense, guns, racial discrimination, and the criminalization of Black bodies.

This narrative is all too familiar. Zimmerman made similar claims after the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2011. Zimmerman claimed Martin posed a threat to his community, in part because Martin was wearing a hoodie. Zimmerman claimed that Martin—who was “armed” with Skittles and an iced tea—was a threat because he didn’t respond to being followed by a strange man, with the “yes, sir” head down humility expected by Black people being interrogated by those who believe they are somewhere they are not permitted to be. Martin’s death and the failure to immediately arrest Zimmerman caused the nation to take notice and Million Hoodie marches were organized across the country, garnering national attention. (Even Beyonce and Jay Z attended one in New York City after the verdict.)

So where is the Million Hoodie march for Renisha McBride?

While there are certainly activists organizing vigils across the country for McBride, they are noticeably smaller at this early stage in the case than the ones organized for Martin. Like Martin, McBride was gunned down inexplicably, and then labeled a threat by the shooter to justify the killing.

There is no question that Black men are under attack by a racist criminal justice system and a society that forever suspects them to be criminals. But when a young Black woman suffers the same fate as Trayvon Martin, the outrage appears to be concentrated among Black women, instead of a universal outrage with mass protests. That has got to change. Black women consistently show up for Black men, and yet the opposite is not true when Black women are the victims of injustice.

That Black bodies cannot simply exist and move about unmolested, without the threat of violence for little to no reason, links us back to the Jim Crow South, when Black bodies were labeled threatening and lynched in front of white communities. As Professor Jelani Cobb wrote in the New Yorker, “African-Americans are both the primary victims of violent crime in this country and the primary victims of the fear of that crime.” Both Renisha McBride and Trayvon Martin died as an apparent reaction to this discriminatory—and common—mindset.

There must be justice for Renisha McBride, for her family, and for her community. Black America is in a constant spin cycle of pain. The reasons given to justify the deaths of Black children are steeped in America’s checkered racial history and white supremacy.

The callousness with which Martin and McBride were killed should compel a national dialogue on race, inequality, profiling, and gun safety, but as long as white Americans refuse to acknowledge that Black people are not inherently a threat, and are capable of innocence deserving justice, the pain will continue. For a nation that claims to have a foundation of freedom and liberty, these killings are evidence of a nation lost and in denial, unable to find its way until all Americans can walk up to a home seeking help after an accident, and not receive a fatal shot to the face.