CMV: The Little-Known Virus That May Endanger Your Pregnancy

Although most of the general public, as well as some in the medical profession, are unaware of the dangers of a CMV infection to the fetus of a pregnant woman, CMV causes more birth defects and congenital disabilities in children than all other well-known diseases.

When I was 22 weeks pregnant with my son, I tested positive for a primary cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. I had most likely contracted CMV during my second trimester of pregnancy, after spending time with some young children.

CMV causes more birth defects and congenital disabilities in children than all other well-known diseases, including spina bifida, Down syndrome, fetal alcohol syndrome, and pediatric HIV infection. Nonetheless, awareness of the dangers of CMV infections in pregnancy is low in the United States, even among some medical professionals.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that in the United States about one in every 150 babies is born with congenital CMV. Although most of these babies will be born without symptoms, one in five will have significant birth defects, including hearing loss, blindness, neurological abnormalities, cerebral palsy, and/or enlarged organs. If contracted during the first trimester, CMV can cause fetal death. Some babies may be born with asymptomatic congenital CMV, but develop problems later in life, the most prevalent being hearing loss. In fact, CMV is the most common environmental cause of hearing loss.

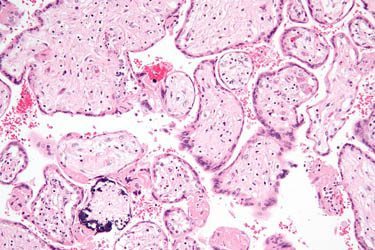

Although not well-known, CMV is a common virus, and between 50 to 80 percent of the U.S. population has contracted it by midlife. Once contracted, the virus remains dormant in one’s body for life. For most healthy people, CMV is harmless, with few, if any, symptoms. It is, however, a danger for pregnant women who contract it for the first time while pregnant, because the virus can cross over the placenta and infect the developing fetus.

According to the nonprofit organization STOP CMV, only about 13 percent of U.S. women are aware of CMV and its dangers to pregnant women, although the people most likely to contract CMV are those working with young children, such as daycare and pre-school professionals, a labor force dominated by women. The most common carriers of active CMV are children under the age of six, who can spread the virus through their tears, saliva, or urine. Although congenital CMV can cause significant problems in infants, children contracting CMV after birth usually have no symptoms beyond those of the common cold, but they can actively shed and spread the virus for several years.

In the United States, there is no routine screening for CMV in pregnant women and little awareness or education. On the STOP CMV website, heart-wrenching stories are featured, written by families affected by congenital CMV. Many include accounts of a lack of awareness by medical professionals—including cases in which pediatricians were unfamiliar with CMV—and the refusal of insurance companies to cover “experimental treatment,” which has been found to lessen the impact of congenital CMV on unborn babies. Almost all of the women featured had never heard of the virus before they were affected by it, even though some of them worked in childcare settings, and many of them contracted CMV during their second or third pregnancies, most likely acquiring it from their own young children.

Unlike in the United States, CMV screening is routine for all pregnant women in eight European countries and in Israel, and is conducted as early as possible in pregnancy. If a pregnant woman is found to carry CMV antibodies, but has no active CMV infection, she has already contracted the virus at some point in her life before the pregnancy and is considered mostly “safe” from CMV, as there is low risk that a secondary infection would affect a developing fetus.

However, if a pregnant woman does not carry CMV antibodies, she has never contracted CMV in her lifetime and is at risk for contracting a primary infection during pregnancy. In these cases, and in countries including Italy, the pregnant woman at risk for a primary CMV infection is educated about the dangers of CMV and is given guidance to avoid infection, including thorough hand washing when in contact with young children, and avoiding kisses on the mouth from any children, including her own. There is currently no vaccination for CMV.

In these countries, a pregnant woman who has not previously contracted CMV will be tested monthly for primary CMV infection, and if she should contract a primary CMV infection at any point during the pregnancy, she has the option of receiving CMV-specific intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, which has been shown to reduce or reverse the impact of CMV on the fetus. These treatments have been met with significant success, but are still considered to be experimental in the United States.

After finding out that I contracted a primary CMV infection during my pregnancy, my insurance company refused coverage of the $10,000 per treatment intravenous immunoglobulin therapy on the grounds that it was experimental. I was lucky enough to be included in a study taking place in Italy, and flew twice to Italy late in my pregnancy, to receive generalized intravenous immunoglobulin therapy treatments. My precious son was born at full-term, healthy, and without congenital CMV.

Like many women, during my pregnancy I avoided alcohol, took folic acid daily, stayed away from litter boxes, didn’t eat lunch meat or rare steak, and did everything else in my power to ensure a healthy pregnancy. But I didn’t know that the potential penalty for not washing my hands after handling toddlers’ toys or not avoiding their sweet little kisses was a potential death sentence for my developing fetus. It also never occurred to me to visit the doctor after I had flu-like symptoms about 14 weeks into my pregnancy.

Surprisingly, despite the progressive actions taken in Europe, the CDC explicitly recommends against screening for CMV in pregnant women in the United States. Dare I suggest that this is due to the powerful health insurance lobby, which doesn’t want to cover routine CMV screening and possible costly treatments for pregnant women?