California’s Prop 35: A Misguided Ballot Initiative Targeting the Wrong People for the Wrong Reasons

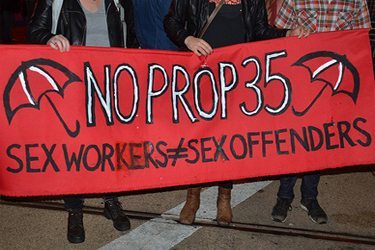

California voters hold the power this Election Day to decide if many thousands of people convicted of prostitution-related offenses in their state must now register as sex offenders.

California voters hold the power this Election Day to decide if many thousands of people convicted of prostitution-related offenses in their state must now register as sex offenders. These are their neighbors, their friends, their family—whether they know it or not—and many are women: trans- and cisgender women, poor and working class women, and disproportionately, they are women of color.

This attack on women already made vulnerable to violence and poverty is just one of the possible consequences of Proposition 35, a ballot initiative marketed to voters as a tough law to fight trafficking but is instead a “tough on crime” measure backed with millions of dollars from one influential donor, written by a community activist with little experience in the issue. If it passes? Advocates for survivors of trafficking, civil rights attorneys, and sex workers fear that rather than protect Californians, it will expose their communities to increased police surveillance, arrest, and the possibility of being labeled a “sex offender” for the rest of their lives.

Trafficking is a hot-button issue, where even defining what is meant by the term is contentious and deeply politicized—but at a minimum, it describes forced labor, where the force may be physical or psychological in nature. The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that nearly 22 million people may be involved in forced labor worldwide, the majority of which does not involve forced labor in the sex trade. In the United States, anti-trafficking law developed over the last ten years has advanced definitions of trafficking. In addition to Federal law, states have passed their own trafficking laws, which overlap with existing laws against forced labor, child labor, minor prostitution, or prostitution in general.

A good deal of advocacy around trafficking is concerned with proposing new laws, with several organizations—such as the Polaris Project and Shared Hope International—focused on introducing copycat legislation state-after-state, focused on increasing criminal penalties associated with trafficking and moving resources to law enforcement. There is little evidence that strengthening criminal penalties and relying primarily on law enforcement are strategies to end forced labor; in fact, advocates who work with survivors of trafficking, as well as people involved in the sex trade and sex worker rights’ advocates, have documented the limitations and dangers of a “tough on crime” approach on trafficking. Still, the “tough on crime” approach has become dominant in what some anti-trafficking advocates now call “the war on trafficking.”

Treating Those In the Sex Trade as Sex Offenders

Proposition 35 adds to this dangerous mix: the overlapping matrix of laws concerning trafficking, the increasingly common conflation of commercial sex with trafficking found in these laws, and the concerns of rights’ advocates. If passed, Prop 35 will create more severe criminal penalties for what it describes as “sexual exploitation”—a potentially far-reaching term that can include any kind of commercial sex, whether or not force, fraud or coercion was present.

Under Prop 35, anyone involved in the sex trade could potentially be viewed as being involved in trafficking, and could face all of the criminal penalties associated with this redefinition of who is involved in “trafficking,” which include fines of between $500,000 and $1 million and prison sentences ranging from five years to life. This is in addition to having to register as a sex offender, and surrender to lifelong internet monitoring: that is, turning over all of one’s “internet identifiers,” which includes “any electronic mail address, user name, screen name, or similar identifier used for the purpose of Internet forum discussions, Internet chat room discussion, instant messaging, social networking, or similar Internet communication.”

Advocates say Prop 35’s conflation of the sex trade with trafficking will not only endanger people in the sex trade, but it will also fail survivors of trafficking. “I think trafficking is very much premised on issues of forced labor – be it forced work, be it forced sexual services,” said Cindy Liou, a staff attorney at Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach, which works with hundreds of survivors of human trafficking.

“Even the division between forced labor and sex work feel extraneous,” she explains. “Our forced labor cases may involve sexual assault, or we may have cases where a client isn’t forced to prostitute herself for money, but is forced to commit sexual acts for noncommercial means – [under Prop 35] that would no longer be considered ‘forced work.’ That said, to confuse prostitution with trafficking is not appropriate, they are separate crimes, and they effect people in different ways. That’s the whole point why they are different crimes.”

If passed, Proposition 35 could also require anyone in California convicted of some prostitution-related offenses as far back as 1944 to also register as a sex offender and submit to lifelong internet monitoring. This is what drove Naomi Akers, the Executive Director of St. James Infirmary, an occupational health and safety clinic run by and for sex workers in San Francisco, to come out hard against the bill. In a Facebook image that spread quickly through sex worker communities online, Akers wrote “I have a previous conviction for 647a” – that is, lewd conduct, one of several common charges brought by California law enforcement against sex workers – “when I was a prostitute on the streets and if Prop 35 passes, I will be be required to register as a sex offender.”

Through Prop 35, “it is possible that people convicted of prostitution-related offenses could be placed on the sex offender registry,” said Juhu Thukral, director of law and advocacy at The Opportunity Agenda and founder and former director of the Sex Workers’ Project. “It is also possible that placement on the registry will be retroactive for some of these offenses.”

Historically and to this day, these charges have been used disproportionately against women in sex work (cisgender and transgender), transgender women whether or not they are sex workers, and women of color, as well as gay men and gender nonconforming people. This is a misguided and dangerous overreach in a bill ostensibly aimed at protecting many of these same people.

Thukral emphasized, “The changes to the existing law [proposed by Prop 35] are complex and not clearly well-written, so this will cause confusion. That confusion as to what properly belongs on the sex offender registry will create damage to people that will likely never be undone.”

Who’s Behind Prop 35?

The problems with Prop 35 extend beyond the language of bill. It appears on California ballots through the aggressive fundraising efforts of its lead advocate, Daphne Phung, executive director of the new non-profit Californians Against Slavery. According to Phung’s bio on the CAS website, her first exposure to the issue of trafficking came from “watching MSNBC Dateline Sex Slaves in America.” After this, though Phung had no previous experience working on the issue of trafficking and no legal expertise, she attempted to introduce a trafficking bill of her own to the California state legislature, who rejected it. Phung then retooled her bill as a ballot proposition, by which a law may be proposed directly to voters if the proposers can gather enough signatures.

This is also when Phung partnered with donor Chris Kelly, the former Chief Privacy Officer at Facebook and one-time California Attorney General candidate, who lost in the 2010 primary to current California Attorney General Kamala Harris. After a high-profile sting in which New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo claimed that Facebook did not intervene in sexually-explicit messages sent to law enforcement decoys posing as minors, Kelly took credit for Facebook’s policy shifts in the wake of these stings and ensuing public outrage, and became an advocate for tracking internet identities in sex offender registries. Kelly is now Prop 35’s lead funder, having contributed over $2.3 million primarily to pay signature collectors to get the proposition on the ballot, and through Prop 35, he is proposing the same measures to monitor sex offenders’ usage of the internet he championed—or was led to champion—at Facebook.

These measures are incredibly alarming to survivors’ advocates. “The sex offender provisions have no place in a trafficking bill,” said Liou, the attorney who works directly with trafficking survivors. “Some of the worst trafficking cases I’ve seen are not sexual and don’t include sexual offenders. It really pits our clients against one another.”

John Vanek, a retired lieutenant from the San Jose Police Department’s human trafficking task force, came into contact with Phung early in the bill’s genesis. He is now working to stop Prop 35. Vanek explained that in the beginning, “the very first draft of what is now called the CASE Act was about two-and-a-half pages long. It was just about raising sentencing standards. [Phung] believes that raising sentencing will have an impact on human trafficking.”

“I would ask,” saids Vanek, “how has higher sentencing worked for our war on drugs on California? It may cut down on recidivism when that person is in custody, but it doesn’t prevent crime. That thinking is flawed. Her thinking is flawed.”

Phung later asked Vanek to support her fundraising efforts for what became Prop 35, despite his objections to her bill. According to Vanek, Phung had “met someone who cannot fund [the] initiative, but [was] willing to host a private gathering in their home, where they would bring in the people who have the money to back this up.”

“She asked me,” said Vanek, “if I would talk about human trafficking for her at those events. I declined—I said I think it would be a conflict of interest. She said, no, you don’t have to ask for the money. I’ll ask for it. But I said no, I was still working with the police department at that time, and I also said, I think this is a flawed way to go about the business here.”

Shortly after this meeting, Chris Kelly came aboard as a funder, and this October, Prop 35 was accepted onto the California ballot.

When “Tough On Crime” Becomes “Tough on Survivors”

In addition to being troubled by the bill itself, Vanek expressed frustration with the number of law enforcement backers of Prop 35, including the San Jose Police Association. “They approved it, but they didn’t take the time to call me up and see what I think about it.” In 2006, Vanek said he helped to found the San Jose Police Department’s anti-trafficking task force, a Federally-funded task force and one of the first in the nation. Since, he’s worked as a trainer for law enforcement on human trafficking. But when it came to this bill, he said, “the culture of law enforcement is they will sign on to anything that seems tough on crime.”

It’s the tough-on-crime approach to trafficking, and the almost singular reliance of Prop 35 on law enforcement to identify and protect trafficking survivors that drives the opposition of victims’ advocates like Liou, who work directly with people who have been trafficked. “This entire bill presumes that if we increase fines and penalties, it will solve the problem.” But, said Liou, “there’s other issues at play – maybe victims feel they can’t come forward, and that there’s no system to support them.”

Based on her experience working with survivors of trafficking in New York state and evaluating and advocating for sound, human-rights-based trafficking policy, said Juhu Thukral, “the criminal justice system cannot be the place that helps people move on from traumatic experiences. It can be a place, if used properly, to seek some level of justice, but it’s not where people are going to be getting long-term support and respect for their human rights that they need.”

Respecting the needs of survivors while navigating relationships with law enforcement already presents challenges for advocates, said Liou.

“With my social service providers, we have an agreement that when law enforcement calls us to accompany them on a raid, we won’t do it. I don’t want to be associated with law enforcement. I like to collaborate with our law enforcement partners, but I make it clear at the end of the day is that we work with our clients, with survivors.”

Prop 35 further risks the relationship between survivors and those working to support them, in part because it privileges law enforcement responses over community-based responses. Advocates for survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault have had to navigate a parallel power dynamic with the police, and it’s one that Liou sees explicitly in her work with trafficking survivors. “Our agency does a lot of DV work,” said Liou, “and to us, [trafficking] is very analogous to this situation. It’s an empowerment model – we work with the victim or the client to say, if you are ready to leave, we’re here to help. But now with trafficking, we’re being told we don’t think about that, it’s about swooping in to conduct a rescue mission?”

The over-reliance on police to “rescue” people who are trafficked, as well as to monitor people convicted of trafficking based on Prop 35’s over-broad definition of trafficking, has worried civil rights advocates in California, as well, with several major state groups urging voters to reject Prop 35.

Claudia Pena, the Statewide Coordinator of the California Civil Rights Commission (CCRC), a membership-based organization of 110 civil rights organizations across the state, explained that the issue of increasing criminal penalties is central to why CCRC voted to endorse a No vote on Prop 35.

“In general, we aren’t in favor of things that increase criminal penalties, because we see people of color incarcerated disproportionately. Increasingly criminal penalties will impact people of color and poor people hardest.”

The American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California have also endorsed a No vote on Prop 35, in part because “the measure requires that registrants provide online screen names and information about their Internet service providers to law enforcement – even if their convictions are very old and have nothing to do with the Internet or children.”

What’s also telling is who has declined to support Prop 35. California Attorney General Kamala Harris, who has supported anti-trafficking measures in the past, and whose office is due to release a comprehensive report on human trafficking California in mid-November, has taken no official position on Prop 35. Not many reproductive rights and reproductive justice organizations have taken a stand for or against Prop 35, though in the last week, Black Women for Wellness published a No endorsement, concerned that under the bill, “young people in the sex trade who are homeless and using strategies to be safer; such as sharing space, food, and resources” could be criminalized by Prop 35, as well as “people of color,queer, immigrant, and low-income communities that are already unfairly targeted by the criminal justice system.”

Trafficking survivors’ advocates have been coming out against the bill as well, though not without challenges. For one, many of the organizations that advocates may have to rely on to help their clients may support Prop 35, which advocates who oppose the bill fear may compromise their working relationships and in turn, their clients. The SAGE Project, a San Francisco based non-profit who works with survivors of trafficking and who has historically taken a stance against prostitution, initially supported Prop 35, but rescinded their support just two weeks before the election. Liou of Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach has been very public about opposing Prop 35, and said of the climate around speaking out against it, “it’s very ‘with us and against us.’ The names I have been called —’oh, you just want to support prostitution, you support pedophiles.’ That’s the sad part of this, the vast majority of my cases are labor cases—and if you consider sex work a form of work, it’s just one industry. This distinction between sex and labor trafficking is ridiculous.”

If people did want to support trafficking survivors, there are existing laws that could make a much bigger impact than Prop 35, advocates said. In California, said Liou, “the Domestic Worker Bill of Rights—that would have been really helpful. A lot of our trafficking cases are domestic worker cases.” The Domestic Worker Bill of Rights did pass the California legislature, but was vetoed this October by Gov. Jerry Brown.

New York, the first state where a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights was passed through the organizing efforts of domestic workers themselves, provides other models for laws that could support trafficking survivors. Said Thukral, “New York state was a leader on vacating convictions” – that is, removing prostitution-related convictions from the records of trafficking survivors. Along with the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, said Thukral, “these are good anti-trafficking laws.”

But by the accounts of these advocates, attorneys, and members of law enforcement, Prop 35 is not really an anti-trafficking bill—it’s an anti-sex work bill, and one with far-reaching consequences for how similar anti-sex work bills, in the guise of “fighting trafficking,” may replicate on its model across the United States.

“If this passes, we are going to see this in other states. So often, as California goes, so goes the nation,” warned Thukral. “It’s frightening. There’s a sense of emotional reaction, married to this really strong anti-sex worker rights agenda. And it’s playing on the public’s emotions.”