Community Networks Provide Free Abortion Pills in Restrictive States—Despite Risks

These community groups are discreet. But their clients still risk criminalization, and networks struggle to meet demand for abortion pills.

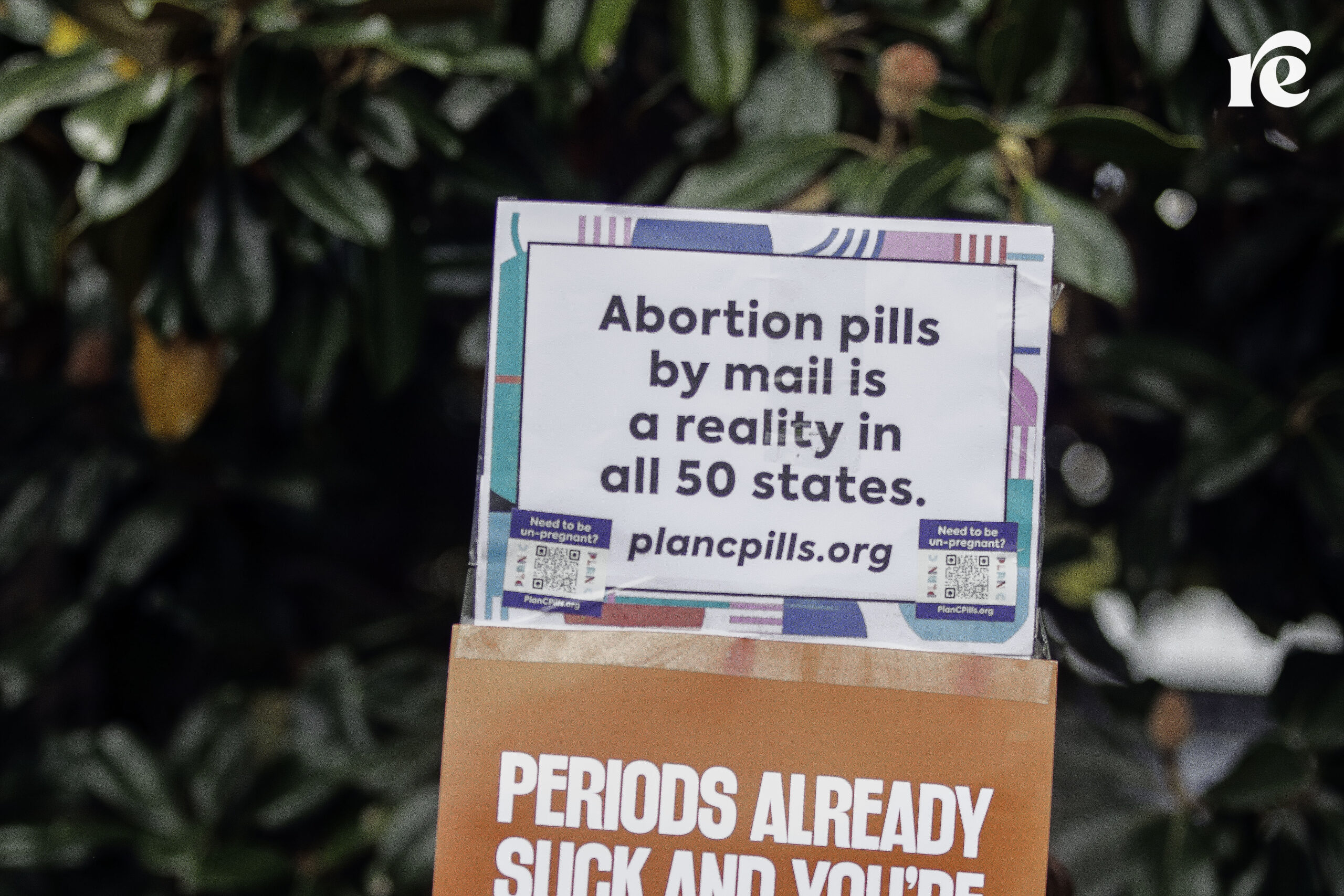

For the last two years, a message has appeared on billboards, in social media posts, and in demonstrations outside the Supreme Court: Abortion pills are still available in all 50 states.

But how real is that promise?

A growing number of states have passed “shield laws” to protect abortion providers who offer telemedicine care to patients in restrictive states, allowing services like Aid Access to work with U.S.-based clinicians and ship pills domestically rather than from overseas. According to the Society of Family Planning, about one-fifth of all abortions recently provided within the medical system were done via telehealth, and thousands each month are provided under shield laws.

Still, even with sliding scale rates, these services aren’t financially accessible to everyone.

“Not everybody has the means or ability to travel,” said Cheryl, a doula who asked to be identified with a pseudonym. “And not only that, many people do not have the ability to pay anything. And many people don’t even have bank accounts, or have a bank account that’s being watched by a parent or an abuser.”

And though it’s fairly easy to buy real abortion pills online, the space is rife with questionable operators who aren’t always reliable.

However, there is another way: Even before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, and before SB 8 went into effect in Texas nearly a year earlier, many people, including Cheryl, were providing others with access to abortion pills within their own communities. After Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, some of them worked to formalize their operations and scale up. They created a network of networks, providing abortion pills to people in most states where abortion is banned or heavily restricted.

Cheryl’s specific grassroots group, which Rewire News Group agreed not to name, covers multiple states and is run entirely by “several dozen” volunteers. According to Cheryl, they have provided more than 70,000 people with abortion pills since 2022—for free.

After more than two years of being hit with one abortion ban after another, however, and following major national cuts to financial assistance for abortion patients, these community networks are—like every group in the abortion access space—struggling to meet a new level of demand.

All-gestation care and the threat of criminalization

Community pill providers like Cheryl’s are listed on Plan C and can also be found at @freepills2024 on Instagram—when they’re not being censored by the app, that is. (As of publication, an Instagram search for the @freepills2024 account brings up a warning that says “this may be associated with the sale of drugs” and directs users to “recovery support.”)

Another factor that sets them apart from more traditional options? They provide abortion pills to people throughout pregnancy.

Though none would speak on the record, several sources in abortion care and the broader reproductive justice movement expressed reservations to RNG about community networks’ provision of all-gestation abortion care, mainly because of the risk that those they help could face criminalization or a continued pregnancy.

In the U.S., medication abortion is only approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use until ten weeks. However, many U.S. providers will now prescribe abortion pills to people who are up to 11, 12, or 13 weeks pregnant, based on ample data showing that this is safe and effective.

In fact, medication abortion has been proven safe and effective in the second trimester and beyond, and is relatively common outside the U.S.—though it’s usually either done in a clinic or hospital, or because someone is being forced to have an illegal abortion. But medication abortions at this stage take longer, which means the process can be more painful. And while the rate of major complications from abortion is exceedingly low, it is slightly higher in the second and third trimesters—and that’s for abortion care provided within the medical system.

When people have access to effective medications and accurate information, research generally finds that complications following self-managed abortion are also rare. However, there is less data regarding self-managed abortion in the second trimester and beyond, and a failed abortion at this point is more likely to require procedural follow-up care.

This potential need for follow-up care exposes people to a greater risk of criminalization.

A 2023 report from the reproductive justice legal organization If/When/How found that between 2000 and 2020, gestational age was mentioned in the vast majority of cases where adults were criminalized for self-managing their abortions. Eighty-seven percent of those cases involved alleged self-managed abortions that occurred in the second or third trimester.

Self-managed abortion is only explicitly banned in two states, and most people who are criminalized for self-managing are charged under other—often misapplied—statutes, such as abuse of a corpse. Of the cases identified by If/When/How, 39 percent were reported to the police by health-care providers, and another 6 percent by social workers, even though self-managed abortion does not fall under mandatory reporting laws.

Mitigating medical and legal risk

According to Cheryl, community pill providers do everything they can to mitigate risk. Cheryl’s network offers each person who contacts them one-to-one doula support if they want it. Anyone who is more than 12 weeks pregnant, under 18 years old, or facing any kind of additional challenges like abuse or homelessness is automatically assigned a doula.

The network considers the criminalization risk of each individual who contacts them, said Cheryl—certain states criminalize self-managed abortion more often, and some people are more likely to face criminalization in general due to their race, citizenship status, income level, or other potentially marginalizing factors.

Cheryl and her fellow volunteers also provide referrals for legal advice and directions on how to dispose of fetal remains when necessary. She added that her network is in contact with medical providers who can answer specific questions when needed.

“We’ve had zero cases of criminalization in the last two years,” Cheryl said.

In the event clients do need to seek medical care, network volunteers “extensively coach people on what to say,” Cheryl said. “I think people’s natural inclination, particularly when they’re scared, is to be honest with the doctor.” And that’s not always a safe prospect.

For privacy, the network gives people the option of receiving their pills in sealed blister packs or loose in a plastic bag.

“The vast majority of the people actually want what I like to call the ‘loosies,’” Cheryl said. “They want something … that doesn’t seem as obvious as a blister pack.”

This, too, is a concern for some experts, because misoprostol—the more important of the two drugs used in medication abortion—degrades significantly when removed from its blister pack. This doesn’t make the medication less safe, but it can make it less effective.

“I’m not worried about personally being criminalized. I am more worried about our patients.”

– Cheryl, a doula and volunteer with a community pill network

Cheryl said her group takes care to make sure pills are not exposed to moisture, and that they go through their misoprostol stock so rapidly that the medication isn’t being stored outside blister packs for long.

She estimated that out of the more than 70,000 people her network has provided with pills, only five or six have needed to seek any kind of emergency care.

Cheryl said she has personally distributed abortion pills for eight years, and in that time has only had to send two people to the hospital. She added that the network has “very low failure rates,” and that when someone’s abortion fails, “we try to troubleshoot it with them.” In some cases, this is because the person hasn’t taken enough medication or hasn’t taken it correctly, and a doula can guide them through the process again and provide more pills if necessary.

And if someone does need medical follow-up care on a non-emergency basis, or simply wants an ultrasound to ensure their abortion is complete, doulas refer them to trusted medical providers where possible.

The looming Comstock Act

Fears of criminalization for pill providers were recently stoked by reporting from The Intercept, which found that federal and local law enforcement have investigated people for sending abortion pills in the mail—though those particular investigations did not result in any arrests.

There is some precedent: As recently as 2020, a New York woman was charged with a federal crime for selling abortion pills online. Ultimately, she was sentenced to probation, fined $10,000, and ordered to forfeit her profit of $61,753.

In that case, the charge was defrauding the U.S. government. However, it is technically a crime to distribute prescription drugs if you aren’t licensed to do so, whether or not you accept money in exchange. Under President Joe Biden, the Department of Justice chose not to pursue such cases, but clearly, the apparatus for a crackdown is in place should the political environment change.

This would be especially true should Donald Trump win the 2024 election.

Using the Comstock Act, an anti-vice law from 1873, to restrict the mailing of abortion pills is a key part of the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 plan to reshape the federal government. And though Trump has publicly distanced himself from Project 2025—in his words, “you have to win elections”—his past appointments would suggest otherwise. Several key Project 2025 figures served in Trump’s first administration, including Roger Severino, architect of Project 2025’s abortion plan and head of the Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights under Trump.

Though Biden’s DOJ has taken the stance that the Comstock Act can’t be used to restrict the mailing of abortion pills, a source told RNG in June that it was this very agency that stood in the way of a full Comstock repeal effort.

Asked what her network would do if the Comstock Act or any other change in federal regulation led to widespread disruptions in their ability to mail pills, Cheryl said she didn’t know.

“It’s very risky,” she said. “I’m not worried about personally being criminalized. I am more worried about our patients.”

Without charge, but not without worry

A key element of the ethos for Cheryl and other community pill providers is that their services are free of charge.

Unsurprisingly, they have seen an increase in requests since the National Abortion Federation and Planned Parenthood Federation of America made significant cuts in the financial assistance they provide for abortion procedures over the summer, leaving abortion funds scrambling to fill in the gaps, Cheryl said.

“We’re also continuously seeing an uptick in patients over 12 weeks,” she added.

At the moment, all this work is funded by individual donors. Together, a group of community pill providers are raising funds via GoFundMe to cover their costs for the rest of the year. The networks have budgets for each state they cover, and when the budget is exceeded, they stop accepting requests from that state. Ideally, Cheryl said, they’d find generous individual donors who wanted to “sponsor” a state and fund access there for a full year.

“One of the big issues is that this isn’t the type of thing that you can write a grant for,” she said. “A lot of the institutional donors, which are the majority, especially when you’re talking about higher-level funds, will not even touch this type of work, particularly since we’re providing all-gestation care.”

The cost per abortion, Cheryl said, is under $15, most of which goes to postage to ensure that the pills arrive on time—or at all, especially in rural areas where mail delivery is less reliable.

“It’s not sustainable for a bunch of people who have other lives to lead to be providing this volume of care.”

– Cheryl, a doula and volunteer with a community pill network

While each individual abortion may be relatively affordable, the high level of demand means financial need is still great. In September, the network’s year-to-date costs had already exceeded $250,000, according to figures Cheryl shared with RNG.

Cheryl and her cohort aren’t trying to out-compete other organizations that provide abortions via telemedicine. To the contrary, Cheryl said she would like to see them do more.

“We need more people providing, and telehealth companies, or the bigger pill providers, we need them providing more care at a higher level,” she said. “They need to do things like hire doulas for one-on-one support, and not charge anything for people who don’t have bank accounts.”

As dedicated as community pill providers are, they’d prefer to be obsolete.

“It’s not sustainable for a bunch of people who have other lives to lead to be providing this volume of care,” Cheryl said.

“We all feel very honored and privileged to be able to provide this level of care for people,” she added. “But the fact that someone’s best situation might be to get something in the mail from a website that their friend told them about and, like, hope and pray that they’re not being scammed … is pretty dark.”