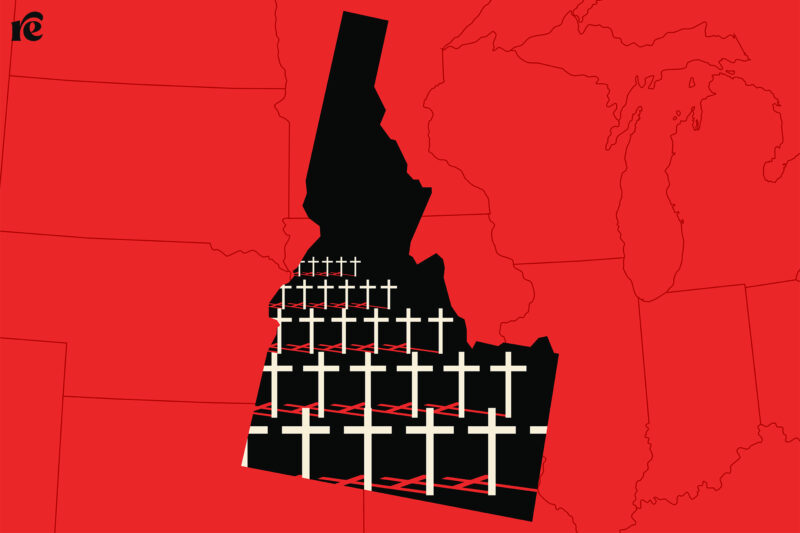

Doctors Warn of Grave Consequences Without EMTALA

If the Supreme Court dismantles the federal right to emergency room abortions, "it would make pregnancy more dangerous throughout the United States."

Can states prevent hospitals from providing emergency abortion care to patients experiencing severe pregnancy complications?

That is the question before the Supreme Court, which will issue a ruling before the end of the term on whether Idaho’s near-total abortion ban can override the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), the federal law requiring Medicare-funded hospitals to provide stabilizing care—including abortion—to all emergency room patients.

After Idaho’s abortion ban went into effect in August 2022, the Department of Justice sued on the grounds that EMTALA, which was enacted in 1986, preempts the state law. The case made its way through the lower courts before the Supreme Court allowed Idaho to enforce the ban on January 5 and put the case (which has been consolidated with Moyle v. United States) on its docket.

The Idaho ban, one of the strictest in the country, only allows abortions in cases of rape or incest, ectopic or molar pregnancies, or to “prevent the death of the pregnant woman.” Physicians face criminal charges and the possibility of losing their license for performing abortions in any other instances, and there are no exceptions to preserve the pregnant person’s health or that of an organ system, such as the reproductive system.

“The way the law is written, in our good faith medical judgment, there has to be a threat to the mother’s life,” Dr. Caitlin J. Gustafson, a family medicine obstetrician and president of the Idaho Coalition for Safe Healthcare, said. However, “emergency situations are not cut and dry, black and white. We don’t wait for people to be on the verge of death until we intervene,” Gustafson added.

The Idaho ban has put health-care providers in an untenable position, as they are trained to prevent catastrophes from happening, said Dr. Rory Cole, a fourth-year medical student in Idaho who is about to start a residency in family medicine.

If a pregnant person goes to the hospital with a severe health condition such as placental abruption, this puts them at great risk of infection, sepsis, and hemorrhage, and “the treatment of choice would be an abortion,” Dr. Jim Souza, chief physician executive at St. Luke’s Health System in Boise, said at an ACLU press briefing in April. That’s particularly true if the pregnant person is preterm and the fetus is pre-viable, meaning there is virtually no chance of survival.

“This is not a rare occurrence in our health-care system,” Souza said, adding that it occurred more than once a week last year. But because of Idaho’s ban, there is now a lot of second-guessing and wondering: “Is she sick enough, is she bleeding enough, is she septic enough for me to do this abortion and not risk going to jail and losing my license?” This type of situation has resulted in some pregnant patients being air-lifted to nearby states after their medical team has determined the patient’s condition doesn’t meet the threshold of the ban.

In the midst of the U.S. maternal mortality crisis, Idaho ranks in the tenth percentile of maternal pregnancy outcomes, according to an Idaho Physician Well-Being Action Collaborative report. The report also found that since the abortion ban was passed, the state has also lost almost a quarter of its practicing obstetricians and more than half of its high-risk obstetricians. The loss has led to three hospital obstetrics programs closing in the state and half of the counties no longer having a practicing obstetrician makes Idaho an “unsafe place” for pregnant women, said Sabrina Talukder, director of the Women’s Initiative at the Center for American Progress.

“If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the Idaho state legislature, they are essentially sentencing mothers to death,” Talukder said.

A ruling in Idaho’s favor means that EMTALA would no longer protect emergency abortion care, affecting every EMTALA-certified hospital in the United States, even if abortion is legal in a state.

It would also set a “precedent that pregnant people are excluded from this protection of an allowance of emergency care,” said Dr. Alexandria Wells, an OB-GYN in Washington state and a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health. “It would make pregnancy more dangerous throughout the United States because there are emergencies that happen when you’re pregnant, and it shouldn’t be up to a politician to determine what that emergency is or what the treatment for that emergency is.”

Even health-care providers in states where abortion is legal are anxious about their ability to continue providing evidence-based care.

“I imagine that if I have a patient come in that has an ectopic pregnancy or is at risk of a miscarriage and needs medication assistance to terminate the pregnancy that’s already on its way to ending, I don’t know if I can go ahead and just treat it,” said Dr. Polly Wiltz, a second-year emergency medicine resident at a community-based hospital in East Cleveland, Ohio.

In that situation, Wiltz said, she would need to consult with a legal team, which leads to a delay in care.

“That will create a huge mess for physicians because you’re going to be afraid to take care of these patients and risk losing your license,” she said. “But then you’re putting people at risk of dying.”

Even with EMTALA protections in place, physicians practicing in the 14 states with total abortion bans have had to deviate from the usual standard of care to comply with the bans, according to a 2023 report from Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health. This included sending patients home from the hospital who had preterm prelabor rupture of membranes and telling them to return when labor started or they were experiencing signs of infection; prior to the ban, the standard of care would have been to immediately offer the option of a dilation and evacuation.

Blocking or criminalizing abortion access sends the message that “it’s OK to discriminate against people who need abortion,” said Dr. DeShawn Taylor, founder and CEO of Desert Star Institute for Family Planning in Phoenix. “It’s just horrible how abortion is the only type of health care where people get a pass for neglecting patients.”

The ripple effect from the harm that the abortion bans cause could include increases in obstetric and reproductive health-care deserts across the country, where there is a lack of obstetric care similar to what is already happening in Idaho and other states with extreme abortion bans.

Kwajelyn Jackson, executive director of Feminist Women’s Health Center in Atlanta, has concerns about the long-term impacts of a potential EMTALA destruction on the workforce.

Jackson said the possibility of criminal charges “might influence someone not to practice in the South or in the Midwest,” or where they receive medical training or complete their residency, not to mention medical school in general.

“I really do believe that over the next several years, we will see a dearth of reproductive health-care providers in states that have made it so blatantly clear that they are willing to undermine the expertise of physicians,” Jackson said.