How to Make the Promise of Suffrage a Reality

One hundred years after ratification of the 19th Amendment, another constitutional amendment is poised to finish the job.

I graduated from the same law school as suffragist Alice Paul. I was apparently more excited about this fact than just about anyone else, because in a law school founded for women by two suffragists, there were no images of its most notable alumna on display (unless you count Judge Judy, which, to be clear … I absolutely do). As a student, I petitioned the administration to retrieve Paul’s portrait out of storage, and they did.

“It was not easy for women to get the right to vote without the right to vote,” legal scholar Julie Suk wrote.

Since our nation’s founding, millions of women across the United States America fought to gain the right to vote and for full constitutional equality—but it is Paul who has been credited with pushing us over the finish line. When the suffrage movement waned, Paul stepped in with the militant tactics she had learned in the U.K. and forced things to a boiling point. She and fellow suffragists committed acts of property destruction, picketed the White House while burning speeches of President Woodrow Wilson, planned a suffrage parade the day before his inauguration, suffered torture and force-feeding in prison, and generally caused such a colossal ruckus they could no longer be ignored.

Women of color also rallied behind the cause of suffrage. In 1912 Chinese American suffragist Mabel Ping-Hua Lee helped lead a 10,000-person suffrage parade in New York City. Women like Zitkála-Ša worked to gain suffrage for Native Americans. Adelina “Nina” Otero-Warren was a prominent Spanish-speaking suffragist and the first Latina to run for Congress. She worked closely with Paul and insisted that the campaign for the vote include bilingual publications and speeches.

All of this incredible activism culminated in the ratification of the 19th Amendment and women being included in the U.S. Constitution for the first time.

“It is incredible to me that any woman should consider the fight for full equality won. It has just begun,” Paul said shortly after the 19th Amendment was ratified. She enrolled in Washington College of Law at American University to learn more about how to change the Constitution. She graduated in 1922 and pivoted her energies to an additional amendment—one that would guarantee full equality.

![[Photo with Mary Church Terrell]](https://rewire.news/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/GettyImages-529094465-375x250.png)

Of course, all over the country women of color did vote. In Tennessee Isabella Ewing voted in 1920, the same year the 19th Amendment was ratified in the state. But racist hurdles like poll taxes, rigged literacy tests, and English language requirements intentionally kept Black voters and other women of color widely disenfranchised. Black suffragist Mary Church Terrell, along with her daughter Phyllis, had risked arrest picketing the White House with Paul in 1917. After the 19th Amendment was ratified, she personally went to Paul and exhorted her to continue the campaign for suffrage until all women could vote.

Paul refused to continue the unfinished fight, leaving women of color behind. Undeterred, Church Terrell carried on the battle for the enfranchisement of Black women through organizations she helped found like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Association of Colored Women.

The Equal Rights Amendment is born

In 1923, at the 75th anniversary celebration of the Seneca Falls Convention, Alice Paul introduced the first version of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which she wrote with fellow attorney Crystal Eastman. It was introduced in Congress in 1923 by Susan B. Anthony’s nephew, and every year after that until it passed in 1972. As with the 19th Amendment, women of color across the country supported the ERA.

In 1948 Mary Church Terrell herself testified before Congress in favor of the ERA, saying, “It is absolutely necessary for women to secure the rights for which they are asking so that they will no longer be the victims of the cruel injustices which will humiliate, handicap and harass them in the future as it has done for so many years in the past.”

![[Photo: Shirley Chisholm]](https://rewire.news/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/GettyImages-615289096-375x250.png)

In 1972, due to the rise of the women’s liberation movement and the hard work of newly elected women like Chisholm and Rep. Patsy Mink, the first woman of color elected to Congress, the ERA passed by an overwhelming majority—354-24 in the House and 84-8 in the Senate. The main clause of the version Congress passed simply reads, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” The ERA was wildly popular, across all political parties and demographics.

Due to the time difference, Mink’s home state of Hawaii ratified the ERA the very same day it was passed in the Senate: March 22, 1972. It was immediately ratified by 22 of the necessary 38 states that first year, but lost steam at the end of the decade as the congressionally appointed deadline loomed near.

Tens of thousands marched on D.C. to extend the ERA deadline. Rep. Barbara Jordan, the first Southern Black woman elected to the House of Representatives, was one of the congressional leaders who advocated for, and won, a three-year extension for the ERA in 1978.

“The Equal Rights Amendment is for men and women,” Jordan said. “It is a constructive force for liberating the minds of men and the place of women. It is inclusive.”

‘Nothing complicated about ordinary equality’

Alice Paul fought for the ERA until her dying day. She died in 1977, the last year any state ratified it for decades. In 1982 the congressionally extended deadline came and went and the ERA stalled, tragically close to ratification. Due to the opposition of male legislators, it fell just three states short—until now.

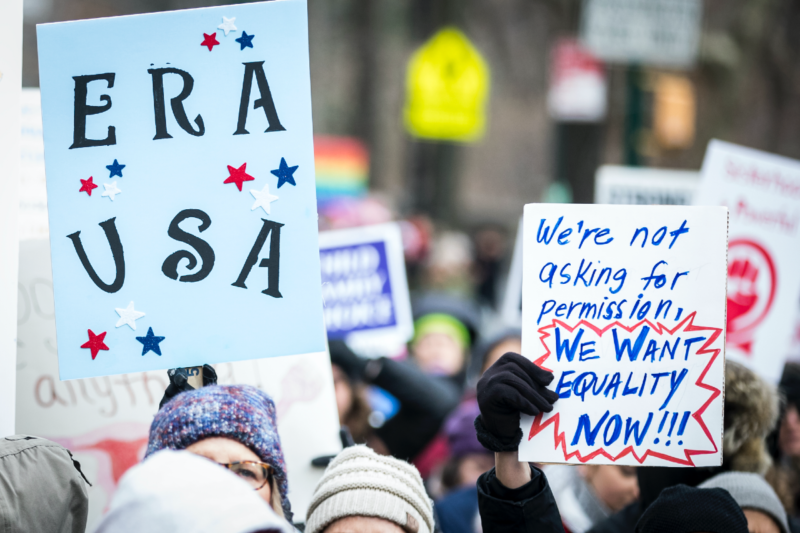

Following the worldwide women’s marches and under the leadership of state Sen. Pat Spearman, a queer Black minister, Nevada ratified the Equal Rights Amendment on March 22, 2017—the first state to do so in 40 years. “I am a woman. I am African American. And I am a member of the LGBTQ community. The discussion of equality is one I’ve been in all of my life. … Equality is not debatable, we are born with it. All we are asking is for it to be recognized,” Spearman said of the amendment.

![[Photo: Pat Spearman addresses delegates in the 2016 Democratic National Convention]](https://rewire.news/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/GettyImages-580956240-375x250.png)

Today, two fights are left unwon—universal suffrage and ratification of the ERA. Obstacles to voting still exist for millions of Americans, including everything from unfair voter ID requirements to felony disenfranchisement. That’s why it’s so important that women like Stacey Abrams have taken up the cause of voter suppression. Just like Mary Church Terrell in 1920, Black women continue the struggle for enfranchisement for all. We can’t celebrate the suffrage centennial without working to make it a reality for every American.

We are also bound together in our collective fight for full gender equality in the Constitution. In the modern era, women of color are still leading the way on the ERA. Alice Paul deserves to be remembered, not hidden in storage. But as we look back, we should reflect on both her accomplishments and her mistakes so we can make different choices and move forward in a more inclusive way.

Though written almost 100 years ago, the ERA is an amendment for our times. With it, we can finally make “We the people” include people of all genders, and help our country live up to its promise of liberty and justice for all. As Paul herself said, “There is nothing complicated about ordinary equality.”