In Anti-Choice Hands, Abortion Clinic Inspections Become a Weapon

Anti-abortion activists routinely use words like “violation” and “fail” to describe minor deficiencies at abortion clinics, making some administrative errors look like gross violations of patient safety.

Like many gynecological offices, Falls Church Healthcare Center in Virginia offers a range of services from annual wellness exams to Pap smears and contraceptives. The center also provides abortion care, which means that since 2011, when the state of Virginia introduced new regulations, it has needed a facility license to operate.

Although abortion care is extremely safe in the United States, it is regulated to a different degree than other health care. If it were a dermatologist’s office, the Falls Church Healthcare Center wouldn’t need a facility license. Not only is it medically unnecessary, but the license is redundant, given that other medical bodies already oversee the abortion clinic’s equipment and staff.

But doctors or health professionals didn’t develop the licensing requirement; politicians did. And as part of that licensing requirement, inspectors from the Virginia Department of Health can visit the Falls Church Healthcare Center at any time, without notice. This is true of abortion clinics in at least 22 other states, according to the Policy Surveillance Program at Temple University.

In interviews with Rewire.News, abortion care providers operating in those states said inspectors often focus on minor cosmetic issues, administrative errors, and other minutiae. They also said the inspections can take up a tremendous amount of time and paperwork; in most cases, the inspections don’t lead to increased patient safety.

When Virginia inspectors visit the Falls Church Healthcare Center, ostensibly to make sure the facility is safe for patients, they don’t examine everything with the same degree of scrutiny, according to Rosemary Codding, the center’s founder and policy director.

“They’re looking at, let’s say, the medical equipment that would be used in patient care,” Codding told Rewire.News. “So we have one cabinet in one of the [procedure] rooms. There’s a cabinet that has the sterile trays and that kind of thing for abortion care. Then there’s another cabinet that has sterile trays set up for colposcopies. They open the first cabinet and look at that, and they go to the next cabinet, and they ask, ‘Is this for abortion care?’” If the medical equipment isn’t used for abortion, “they close the cabinet and don’t look at that,” Codding said.

Most critically, the anti-choice movement has used the inspections, and the resulting reports, as a political tool to target abortion providers with false claims of unsafe practices. Part of an age-old tactic of fear mongering, anti-abortion activists routinely use words like “violation” and “fail” to describe minor deficiencies, making some administrative errors look like gross violations of patient safety.

In some cases, state health officials use these inspections to restrict access to abortion care.

For over a year, Whole Woman’s Health has been trying to open a new facility in South Bend, Indiana, a state that has seen many abortion clinics close in the wake of anti-choice laws. There are only six abortion clinics left in the state, and none in South Bend. While sparring with state regulators over minor details in its license application, Whole Woman’s Health has been hit with a flood of negative articles in anti-choice publications falsely stating that its other locations are riddled with health and safety violations. The clinic applied for a facility license 18 months ago but has yet to receive one.

The clinic has now asked a federal court for emergency relief from Indiana’s licensing requirements, arguing that the state has unnecessarily delayed the organization’s request for a license to operate the clinic in South Bend. “It has become apparent that officials at the Department of Health have a political agenda and have no intention of granting us a license,” Amy Hagstrom Miller, founder and CEO of Whole Woman’s Health, said in a statement.

The state’s attorney general is backing the health department, arguing that licensing requirements are necessary for patient safety. In court documents filed this week, the attorney general also claimed the state’s delays are warranted because “several surveys indicate” that other Whole Woman’s Health clinics have “violated numerous health codes,” a reference to the inspection reports.

“When I started in the field almost 30 years ago, there wasn’t abortion clinic licensing like there is now,” Hagstrom Miller told Rewire.News. “Facility licensing started in the ‘90s. It wasn’t that all of a sudden, abortion got more complex. It was a political strategy.”

Even without facility licenses, abortion providers still answer to other regulatory bodies. Most medical practices are regulated by the professional associations or accreditation organizations that set standards for patient health and safety in a given field. For abortion providers, these include the National Abortion Federation (NAF) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). The doctors and nurses who work at abortion clinics are licensed, and the government regulates the laboratory equipment they use.

“Health care is incredibly regulated,” said Sarah Roberts, DrPH, an associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who studies abortion restrictions. However, as a result of anti-abortion legislation, many state health departments now find themselves in a position of “enforcing regulations passed by the legislature that don’t necessarily have a public health purpose,” Roberts said.

“What’s weird here is that one particular type of facility is being singled out without any evidence to say that is warranted.”

Using “Violations” to Demonize Abortion Clinics

Despite the demands that licensing requirements put on them, the providers who spoke with Rewire.News said they do their best to comply with health and safety inspections because they don’t want to do anything that would put the clinics, or patients, at risk. “We take our inspections and the regulations very seriously … even if we don’t agree they improve patient care,” said Kim Chiz, executive director of Allentown Women’s Center in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

“The issue is the way that the deficiencies are communicated and how they can be taken out of context.”

Kimberly Beazley, deputy director of the Office of Licensure and Certification at the Virginia Department of Health, said “a survey report and plan of correction are only published after they are considered acceptable and the survey is finalized.”

In other words, clinics have already addressed any deficiencies that are cited in these inspection reports.

Finished inspection reports are publicly available through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, and all of the abortion providers who spoke to Rewire.News for this story believe they should be public. The problem, they say, is that the reports are often weaponized.

In framing state inspection reports as evidence of “violations” at abortion clinics, anti-abortion groups can demonize clinics while giving political ammunition to those who believe the clinics are not regulated enough. In Texas, Republican lawmakers recently introduced a bill that would make clinic license applications public, making providers even more vulnerable to harassment by anti-abortion activists that target clinics themselves. For example, activists might use a clinic’s address to intimidate a landlord or lobby against the clinic before it even opens, according to Anjali Salvador, staff attorney at the ACLU of Texas. In Maryland, activists a few years ago harassed longtime owners of two abortion clinics in the state until they broke down and sold the buildings, causing the clinics to close.

Activists in Texas have already obtained copies of the inspection reports even before clinics added their plan of correction. Publishing these versions makes it seem as though the clinic has done nothing to fix the problem.

“What they’re giving you is only half the conversation,” said Hagstrom Miller. “For them to show a report without a plan of correction is political.”

Abby Johnson, a former Planned Parenthood clinic director, has been a driving force behind the mischaracterization of clinic inspection reports with her anti-abortion nonprofit, And Then There Were None. Johnson’s memoir was recently made into an anti-abortion film.

In 2018, Johnson founded CheckMyClinic.org, a database of clinic inspection reports that purports to educate patients but in reality paints a skewed picture of clinic safety.

Visitors on CheckMyClinic.Org can search by state and find pages for nearly every abortion clinic in the country with lists of that facility’s “health violations.” In fact, the “violations” they cite are not actually called violations by health inspectors. “We use the term deficiency as opposed to violation,” Beazley said.

“A violation means the health department has concluded you are endangering the life and safety of somebody,” Hagstrom Miller said.

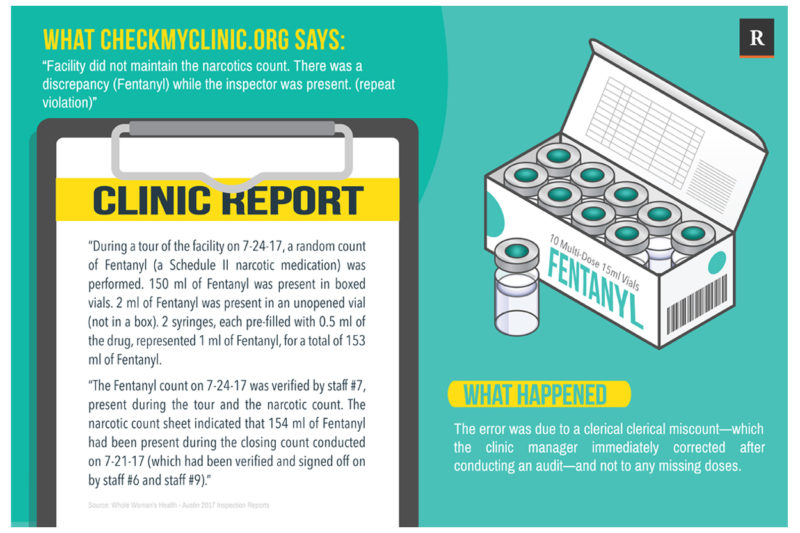

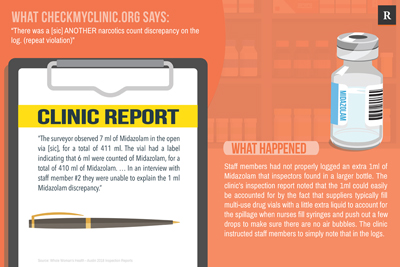

A patient might read on CheckMyClinic that Whole Woman’s Health in Austin had a “repeat violation” of a “narcotics count discrepancy.” With many communities in the United States currently suffering from an opioid crisis, a narcotics “violation” is enough to raise an alarm.

In reality, the clinic was cited for two deficiencies for minor errors. In the first, a clerical error led to a 1ml discrepancy in the clinic’s fentanyl count, which was immediately corrected. The second deficiency was cited because staff members had not properly logged an extra 1ml of midazolam found in a larger vial. According to the clinic’s inspection report, the 1ml could easily be accounted for by the fact that suppliers typically fill multi-use drug vials with a little bit extra liquid to account for the spillage when nurses fill syringes and push out a few drops to make sure there are no air bubbles. To fix the deficiency, the clinic instructed staff members to simply note that in the logs.

“The regulation they cite makes it sound like we’re mishandling narcotics, when actually the manufacturer has an extra ml in there on purpose,” Hagstrom Miller said.

Abortion care providers in three states—Virginia, Texas, and Indiana—have brought lawsuits to challenge state licensing requirements, among other restrictions on abortion clinics they believe are unconstitutional following the Supreme Court’s decision in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. According to the lawsuit brought in Virginia (in which Whole Woman’s Health and Falls Church Healthcare are both plaintiffs), one clinic was “cited for a deficiency when its staff physician had water spots on his lab coat.”

Another clinic said it had been inspected as much as three times in one year, even though the regulations only require inspections of abortion clinics at least once every two years.

“The Outcomes for Our Patients Aren’t Improved”

Jennifer Groves is the executive director of Cherry Hill Women’s Center in New Jersey and Philadelphia Women’s Center in Pennsylvania, both states with licensing requirements.

Groves said many of the inspectors who visit her abortion facilities don’t fully understand how abortion works and how it’s regulated. In the Philadelphia clinic, after a volunteer re-painted the walls of the center, Groves said an inspector grilled her about whether she had asked the health department for permission before painting, something she isn’t required to do. “Which doctor’s office would have to do that?” she said to Rewire.News.

Some inspectors seem to feel personally uneasy with abortion, making the inspection process even more difficult than it already is, Groves told Rewire.News. “I’ve had inspectors who refused to go into the clinic and made me grab all of the paperwork we have and put it in a conference room next door,” she said.

Groves previously worked in the hospital at the University of Pennsylvania, where part of her job involved complying with inspections by the Joint Commission, the nonprofit regulatory body that inspects hospitals. “It was intense,” she said of the commission’s hospital inspections, “but nowhere near as intense as the abortion clinic inspections I’ve participated in.”

The time clinic staff have to spend preparing for and complying with state health department inspections takes resources away from patients, according to the providers who spoke to Rewire.News.

“In states where there is this kind of onerous regulation, my staff start to feel like they’re practicing for the regulations,” Hagstrom Miller said. “In Minnesota, we don’t have clinic licensing. Our complication rate, our infection rate, our quality scores, it’s all the same. The outcomes for our patients aren’t improved in states where we have clinic inspections.”

The Very Reverend Katherine Ragsdale, interim president and CEO of NAF, said she has “no doubt” that this is true.

NAF conducts routine quality assurance checks of its members, which are independent abortion clinics across the country. The organization doesn’t track data that would compare clinics in licensing states to those in non-licensing states, but Ragsdale said she’s never noticed any difference in care.

“Our members are going to be providing quality care regardless of whether they’re in a regulated state or not,” she told Rewire.News. “Unless they’re in a state so regulated that they’re not providing any kind of care, because they can’t get a license.”