5 Key Moments From the Year of the ‘Exvangelicals’

We've used our increased visibility, often through hashtag campaigns, to expose evangelical authoritarianism to the broader American public, something that major media outlets have mostly failed to do.

When we look back at 2018 a couple of decades from now, we may well recognize it as the year that a cohort of former evangelicals—largely children of the 1980s and 1990s who were mobilized for the culture wars we now repudiate—broke into the American public’s consciousness. These ex-evangelicals—often referred to as “exvangelicals” or “exvies”—are part of a broader generational moment marked by a conservative Christian nationalist backlash against rapid secularization, civil rights, and social movements aimed at exposing abuse and patriarchal exploitation of women.

The election of Donald Trump with massive white evangelical backing became a flashpoint and catalyst for the coalescing of individual disaffected former evangelicals into a growing community and movement with certain identifiable features and goals. Because the exvangelical community consists of those who repudiate evangelicalism for its pervasive authoritarianism, we also tend to affirm that which most white evangelicals—a literally uniquely conservative, uniquely pro-Trump, and nativist demographic—stand against.

Exvangelicals, then, are by and large proponents of feminism, intersectionality, racial justice, and LGBTQ rights. We don’t seek a common metaphysics or (a)theology, but rather seek to build bridges between those of us who have left evangelicalism for no religion and those of us who have departed for healthy religion. Many of us have religious trauma, and we began finding each other around the time of the 2016 election to foster our own healing through mutual understanding and the validation that comes from knowing we’re not alone. Leaving hardline faith communities can, after all, be extremely isolating.

At the same time, we’ve used our increased visibility, often through hashtag campaigns, to expose evangelical authoritarianism to the broader American public, something that major media outlets have mostly failed to do. Exvies contend that we are stakeholders in national discussions of evangelicalism, and should be treated as such. In 2018, we made significant progress in terms of gaining a recognized presence in the public sphere.

The following highlights cannot possibly represent a comprehensive picture of significant exvangelical achievements made this year, and this list is inevitably subjective and shaped by my own bias as a prominent ex-evangelical voice. Nevertheless, they should serve to illustrate that exvangelicals are becoming an established public presence. Conservative, mostly white evangelicals have controlled their own narrative for too long.

While the exvangelical community lacks their institutional infrastructure and deep pockets, we have nevertheless—no doubt assisted by the sustained robust support for Trump from white evangelicals—managed to curtail the evangelical establishment’s control over their media representation, and we have managed to get our voices heard. This is a momentous accomplishment.

***

5) Urban Dictionary Adds Exvangelical Definition of “Beverly”

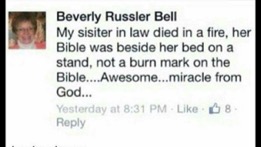

Some readers of RD may remember how a post by a woman named Beverly Russell Bell, who praised God for sparing her sister-in-law’s Bible when the sister-in-law herself died in a fire, went viral in 2016.

When the “Beverly meme” appeared in the Exvangelical Facebook group, a support group and intersectional safe space that now has nearly 4,000 members, then-member and now moderator Anne Weaver suggested we refer to tone-deaf evangelicals as “Beverlies.” As of late 2018, Urban Dictionary has added the definition:

4) Best Exvangelical Hashtags of 2018

The quickest way to get a general sense of what exvies are like is to read exvangelical Twitter. Exvies have a pattern of demonstrating creativity and social media savvy by creating hashtags that range from the whimsical and snarky to the deadly serious. Community standbys include #Exvangelical, coined by Blake Chastain in connection with his podcast of the same name, and #EmptyThePews, which I coined initially as a means of protesting evangelical complicity in the atrocities that took place in Charlottesville in August 2017.

Hashtag highlights from 2018 include the snarky #HowToEvangelical, a perfectly millennial phrase first crafted, to the best of my knowledge, by Twitter user @petuniasfalling, who tweeted “how to evangelical: gaslight yourself, constantly” on March 27. I suggested we hashtag it, and #HowToEvangelical quickly trended, hitting over 10,000 tweets in a day.

In addition, exvangelical Twitter helped bring attention to the fundamentalist Clarks Summit University’s mistreatment of Gary Campbell, a man who had left the school years prior and now wanted to re-enroll to finish his degree, needing only six credits. Clarks Summit (formerly Baptist Bible College) initially accepted Campbell, but, on discovering that he is now an out gay man, rescinded the acceptance. To protest the move, we created the hashtag #LetGaryGraduate, which helped bring visibility to Campbell’s cause.

While Clarks Summit did not respond to the public pressure and media exposure, Lackawanna College learned of the situation and found a way to allow Campbell to transfer most of his credits. In addition, Heartstrong, an organization dedicated to supporting queer students at oppressive religious colleges, provided Campbell with a scholarship to help defray the higher cost of finishing school at Lackawanna.

Exvangelical hashtags first created in 2017 also remained relevant in 2018. #ChristianAltFacts, a hashtag I coined to expose the “alternative facts” taught in Christian schools, homeschooling curricula, and evangelical churches, made a splash in November. And #ChurchToo, created by Emily Joy and Hannah Paasch, continued to make a powerful impact, about which more below.

3) Exvangelicals Go Offline

Since exvangelicals are geographically scattered, community building until now has taken place mostly online. In 2018, however, exvangelicals organized some public offline events, hoping to inspire more local community formation and to build synergy between online and offline activities. Exvangelicals successfully crowdfunded a roundtable discussion—The Exvangelical Community: Paths, Projects, Prospects—that took place at St. Petersburg College in Clearwater, Florida, on September 8. The panelists were introduced by Blake Chastain, who also recorded the event and released the audio later as a special episode of his podcast, Exvangelical.

At the event, journalism professor David Wheeler talked about his experiences studying in, and teaching at, an evangelical college; Kathryn Brightbill talked about her Christian Right homeschool upbringing and her policy work with the Coalition for Responsible Home Education; and Akiko Ross gave a moving account of her experiences as a woman of color teaching Sunday school classes and leading women’s groups in Southern Baptist churches for decades, and why 2016 was the final straw for her. I discussed exvangelical advocacy and social media presence, while Religious Studies Professor Julie Ingersoll served as a discussant who was able to masterfully contextualize these topics.

Meanwhile, exvies Josiah Hesse, Alessandra Ragusin, Amanda E.K., and Ryan Connell, who attended the Florida roundtable, were traveling the country on The Unapologetics Tour, in connection with which they visited sites important to evangelical history and subculture, interviewed numerous exvangelicals, and held book readings and events related to the launch of journalist and novelist Hesse’s second novel, Carnality: Sebastian Phoenix and the Dark Star. One of these events took place at City Lit Books in Chicago on Friday, October 12. The well attended event, audio of which is also available as a special episode of the Exvangelical podcast, concluded with an interview with Josiah, conducted by Blake Chastain and yours truly.

Meanwhile, exvies Josiah Hesse, Alessandra Ragusin, Amanda E.K., and Ryan Connell, who attended the Florida roundtable, were traveling the country on The Unapologetics Tour, in connection with which they visited sites important to evangelical history and subculture, interviewed numerous exvangelicals, and held book readings and events related to the launch of journalist and novelist Hesse’s second novel, Carnality: Sebastian Phoenix and the Dark Star. One of these events took place at City Lit Books in Chicago on Friday, October 12. The well attended event, audio of which is also available as a special episode of the Exvangelical podcast, concluded with an interview with Josiah, conducted by Blake Chastain and yours truly.

2) Exvangelicals Make National News, Including Television Debut

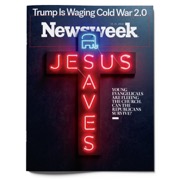

In 2018, exvangelicals continued to make progress in terms of media representation, with our perspectives being considered in the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, the New Republic, Salon, and other outlets. Exvangelicals were even featured in Newsweek twice, including in the cover article of the print edition for December 21.

The biggest exvangelical media breakthrough thus far, however, is surely the CBS special “Deconstructing My Religion,” written and produced by Liz Kineke, and which began running on CBS affiliate stations earlier this month. The special prominently features Linda Kay Klein, author of Pure: Inside the Evangelical Movement That Shamed a Generation of Young Women and How I Broke Free, the September publication of which should be placed alongside the release of the Boy Erased film adaptation of Garrard Conley’s 2016 memoir about “ex-gay” therapy as major exvangelical phenomena of the year.

In addition to Klein, “Deconstructing My Religion” features me, Blake Chastain, and Emily Joy, as well as scholarly commentary from Julie Ingersoll.

1) Exvangelicals Prevent Evangelicals from Taming the #ChurchToo Critique

In my view, the greatest exvangelical triumph of 2018 came this month when the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College held one of its “GC2” (Great Commission/Great Commandment) Summits dedicated to abuse in the church—initially using the #ChurchToo hashtag to promote the event. Thanks to the efforts of exvangelicals, the event failed both to coopt a hashtag whose creators correctly see evangelical purity culture and patriarchal teachings on sexuality as drivers of evangelicalism’s widespread abuse and sexual assault problem, and to control the media narrative surrounding the event.

Key event organizer (and evangelical spin doctor) Ed Stetzer, along with headliner Beth Moore, ignored weeks of concerned tweets from numerous exvies and Christian survivors of sexual assault (such as Jules Woodson) that a conference addressing #ChurchToo should consider the views of the hashtag’s creators, and that without addressing the elephant in the room—a theology of “male headship” and a culture of unaccountable white male leadership—there’s no solution to the problem of abuse in evangelical and fundamentalist institutions.

Moore and Stetzer apparently assumed that giving their critics the silent treatment would have no impact on the event’s ability to get good press, because that has worked for them in the past. This time, however, they couldn’t have been more wrong. Emily Joy, Hannah Paasch, Samantha Field, Charlotte Henderson, and Nate Sparks organized an online counter-event on December 13, the day of the Wheaton summit.

Organizers made and distributed memes featuring homophobic and sexist quotations from the conference headliners, such as “We’ll always wonder if Bathsheba was bathing in a place where she shouldn’t, hoping David would look where he shouldn’t look,” from summit headliner and celebrity pastor Max Lucado. Field paid the $25 fee for access to the summit’s live stream and live tweeted the entire thing. Henderson created a blog post for the occasion about how she had been affected by evangelical purity culture as a queer black woman, and the organizers and participants in the counter-event amplified her piece.

And the news media noticed, documenting the counter-event and taking the concerns of the conference’s mostly exvangelical critics seriously. The way the Wheaton summit was covered likely blindsided the conference organizers, who have been accustomed to controlling their media representation. Since then, exvangelical Twitter has continued to explore what was wrong with it, with Michelle Panchuk producing an important thread on why the “best practices” document released by the summit organizers doesn’t represent a serious understanding of best practices, and will thus fail to prevent abuse.

2018 is the year that exvangelicals broke through and began to change the national discussion of evangelicalism in a serious and sustained way. Look for more snarky and serious hashtags, Urban Dictionary definitions, offline events, media representation, and bigger breakthroughs in 2019.