As Laws Target Minors’ Abortion Rights, These Groups Help Them Get Access

Abortion funds and youth nonprofits help young people navigate the legal system to get judicial approval for abortion, push repeal of parental notification laws, and support youth advocacy.

Since January, hundreds of anti-abortion bills have moved through state legislatures across the country, but historically, some of the most longstanding restrictions have targeted young people seeking abortion care. Minors face many barriers not always related to age, such as medically inaccurate sex education (or none at all), lack of birth control, and limited resources. But with a new round of parental notification laws, minors’ abortion access may be narrowing to the point of near-impossibility.

In the state of Indiana, a bill that would require minors to get parental consent prior to having an abortion was signed into law until a federal judge blocked it from taking effect this June. In West Virginia, a provision allowing doctors to grant waivers to minors seeking abortions due to health risks was repealed in April, leaving minors to either obtain a parent or guardian’s consent or a judge’s approval. And Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall filed paperwork last month to appeal a July decision that blocked the state’s requirement that minors undergo a trial-like hearing to obtain a judge’s approval for an abortion.

“Young people, minors, are definitely the demographic facing some of the most serious restrictions on their bodily autonomy, and these laws regard their bodies as their parents’ property,” said Amanda Bennett, the client services manager at Jane’s Due Process in Texas. “Here in Texas, where there’s so few abortion clinics, the problem is really exacerbated.”

Jane’s Due Process is a nonprofit that supports reproductive justice for minors by offering help with navigating the process to obtain judicial bypass, the legal waiver that allows them to have abortions without parental consent. As of 2017, 37 out of 50 states have parental consent laws for minors seeking abortion. The 1979 U.S. Supreme Court decision of Bellotti v. Baird ruled that minors do not need parental consent to obtain the procedure, but granted that as long as they have the option of obtaining judicial bypass for the procedure, such parental requirements are feasible.

Jane’s Due Process also refers minors to Fund Texas Choice for financial assistance for other services they may need, such as transportation or lodging. In 2016, Jane’s Due Process completed intake with 307 minors, although only 200 went on to work toward obtaining bypass; some minors with unintended pregnancies will have miscarriages, travel out of state, or even end up telling their parents or trusted adults further down the line.

The judicial bypass process starts with minors seeking abortions calling Jane’s Due Process’ hotline or completing its online intake form. Next, the organization arranges for an ultrasound and an attorney paid for by the state. Within five business days, a hearing is scheduled with a judge. A recent law requires hearings to take place in the minor’s county of residence rather than where they will have their abortion, and this has sometimes complicated the judicial bypass process, according to Bennett.

“Judges in counties [without abortion clinics] tend to be less equipped to deal with these situations, and the hearings can get messy,” she said.

Young people receive judicial bypass if the judge deems that the minor is mature and informed enough to make the decision, or if the judge finds that the minor’s family situation merits the procedure. In many cases, minors are able to obtain the waiver. But in July, a 12-year-old victim of rape and child abuse in Alabama was denied an abortion by a district attorney and only granted judicial bypass when a circuit court intervened.

Still, according to Bennett, even though most hearings with judges do result in minors being granted judicial bypass, this doesn’t change the inherent problems with the hearings, which are not dependably confidential. In examples from Minnesota and Massachusetts, according to StopPNA.org, “one young woman was sitting in a court corridor when her sister’s civics class came through; another saw a neighbor in the courthouse; a third encountered her godmother, who was employed as a court officer; another had to hide in the bathroom to avoid being seen by a family member who worked in the courthouse; and a young woman ran into her father right outside of the courthouse.”

Young people can also face hostile gatekeepers. Quita Tinsley of the Access Reproductive Care-Southeast abortion fund in Georgia recalled when “a young person called us after she had been to her local courthouse in Georgia to ask about judicial bypass. They lied and told her they didn’t know what she was talking about. They tried to act like it didn’t exist. We knew it existed, and we were the ones who had to help her navigate that process and get her a lawyer to be able to get her judicial bypass.”

Abortion funds know firsthand that the circumstances surrounding young people accessing abortion are already incredibly difficult. From 2010 to 2015, the National Network of Abortion Funds’ George Tiller Memorial Fund served a total of 481 young people under the age of 18. The majority of adolescents were geographically located in the South (50 percent) and Midwest (20 percent), and had to travel an average of 185 miles. The young people who called for funding were predominantly Black (59 percent) and ages 14-to-15 (36 percent) or 16-to-17 (56 percent). Of the 204 adolescents who reported information on the reason for obtaining an abortion, the primary driver (61 percent) was not having access to birth control. And for many young people, there were extenuating life circumstances, such as some form of government assistance, having multiple children, seeking an abortion due to being raped, and having partial or unstable living situations.

The average cost of young people’s abortions funded by the Tiller Fund was $2,800, three times what the patients could afford. The cost was magnified because more than two-thirds of the adolescents sought abortion care in the second trimester of pregnancy.

Bennett noted that while minors are matched with attorneys at no cost, there is no public funding for abortion in Texas. A recent study associated the defunding of women’s health and family planning clinics in Texas with higher rates of abortion in teens. It’s worth noting that there’s also a statewide crisis of poor sexual health education in public schools and households that contributes to unplanned pregnancies among people of all ages.

West Virginia FREE is another abortion funding organization that helps minors access abortion care. Working with the Women’s Health Center of West Virginia, the last abortion clinic in the state, West Virginia FREE offers financial support for the abortion procedure, as well as transportation and lodging expenses for people who must travel out of state due to the state’s ban on 20-week abortions. The group also connects patients with an attorney from its judicial bypass network.

According to Julie Warden, West Virginia FREE’s communications director, only two waivers were used in 2015, and none in 2016. “It’s rare, but no less burdensome for the people who have to go through that process,” Warden said.

Yamani Hernandez, the executive director of the National Network of Abortion Funds, saw how difficult accessing abortion could be for youth when she was executive director of the Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health (ICAH).

Hernandez noted: “Young people of color, undocumented youth, transgender youth, and others are already too often criminalized because of their very identities. Young people who have been neglected by the systems that are charged with supporting them are often hesitant to enter the court system. Too many youth experience stigma around their decisions at home, school, and in health-care environments. Legislators interested in targeting youth with these laws need to take a giant step back and reconsider the consequences of the obstacles they are setting up.”

Hernandez, current ICAH Executive Director Tiffany Pryor, and groups such as the ACLU of Illinois support youth and center their voices in the ongoing effort to end forced parental notification in that state. “Every young person is in a different situation when they seek abortion care,” Pryor said. “For reasons of safety, fear of homelessness or violence, abuse, and neglect, it’s not ethical to require parental notification.”

As anti-abortion lawmakers ramp up efforts to limit abortion access in the months to come, young people aren’t silent. They’re fighting back.

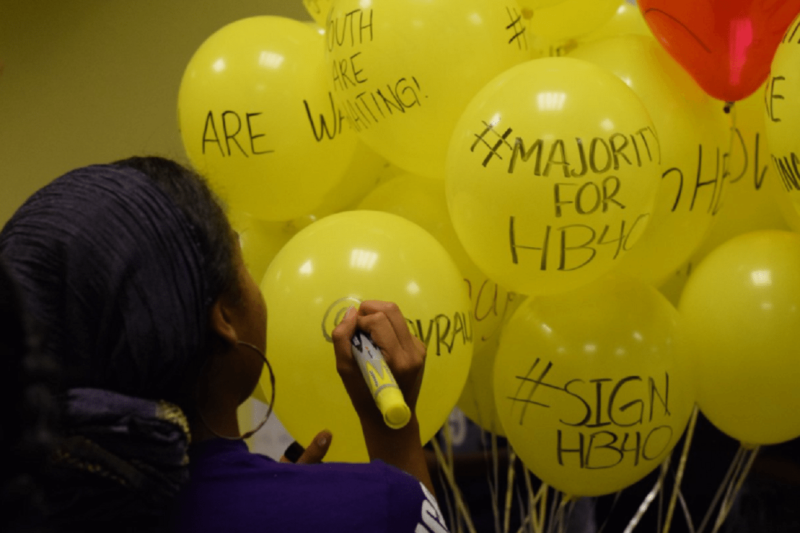

In Illinois, Pryor described local efforts led by youth. “Recently, young people at ICAH have organized and demanded Gov. [Bruce] Rauner sign HB 40, legislation that would allow every person, whether covered by private or government-funded health insurance, to have affordable and comprehensive health care, including abortion care.”

Paula Mejia, a young activist with ICAH, says of the HB 40 action in Illinois: “It’s been so incredibly rewarding to work with other young people who are passionate about issues of social justice. … We urge Governor Bruce Rauner to #SignHB40 and keep his promise to not interfere with reproductive rights. It’s already been passed by the House and the Senate of Illinois, and that’s why we say #MajorityforHB40.”

Another young person, Brie Garrett, says: “Health care is our human right, and everyone deserves to have access to opportunities and systems that help their lives. HB 40 helps lower-income people, people of color, women, and people who can get pregnant.”

In the abortion access movement, we often tout unapologetic abortion access for anyone who needs it. But until young people are heard loud and clear and supported in their reproductive decisions, abortion access for all will not be a reality.

CORRECTION: This article has been updated to clarify that Jane’s Due Process refers minors to Fund Texas Choice for transportation funding or lodging.