A Trump-Run CDC Could Mean ‘Sham Science’ as Government Policy

“Public health is one of these disciplines where nobody really thinks about it until there is a crisis,” says Caitlin Gerdts, vice president for research at Ibis Reproductive Health.

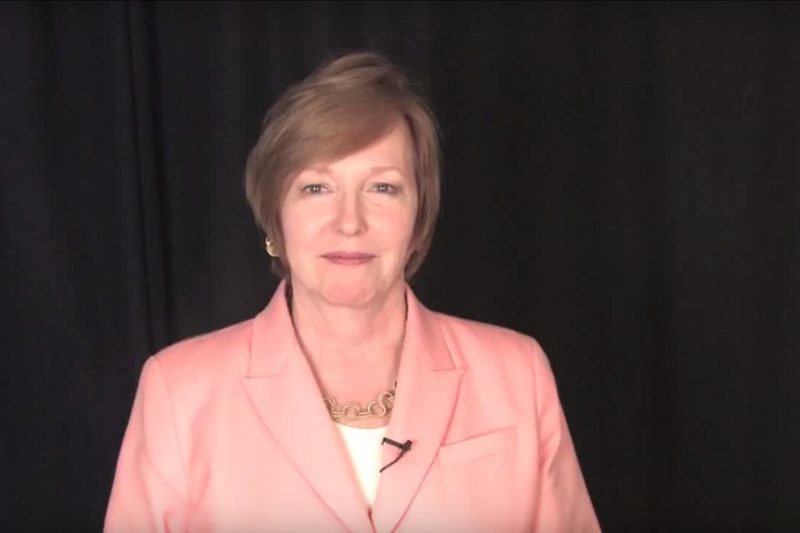

The Trump administration announced in early July that Brenda Fitzgerald, a Georgia OB-GYN and the state’s commissioner of public health, would head the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), raising questions about the potential effects of politically-charged decisions by the critical agency.

Researchers who track the relationship between public health policy and reproductive rights said a CDC chief’s actions can have wide-reaching consequences.

“Public health is one of these disciplines where nobody really thinks about it until there is a crisis,” says Caitlin Gerdts, vice president for research at Ibis Reproductive Health.

Gerdts, a reproductive epidemiologist, told Rewire that while many don’t consider the importance of public health until there is “some kind of disease outbreak or a public health system failure … we are all, every single day, living with the benefits of centuries now of important public health interventions—anything from refrigeration, to vaccination, to sanitation has all come from public health.”

That is just one of the reasons why the work the CDC does is so important. Among its public health initiatives are programs that focus specifically on reproductive health research. According to Gerdts, “paying attention to and advancing the science around preventative health care and reproductive health, and access to reproductive health, is a critical function of the CDC.”

Lawrence B. Finer, vice president for domestic research at the Guttmacher Institute, told Rewire that the CDC’s work “makes contributions to not just health treatment, but health research in a very broad range of areas,” including reproductive health. Citing the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) as an example, Finer explained that the program functions as “an incredibly important source of information on data on health in the U.S., specifically with regards to reproductive health.”

The NCHS collects data used to drive policy, and one of those data sets—the National Survey of Family Growth—is “probably the most important survey of reproductive health behaviors” in the country, Finer said.

That survey is “the best source of information in the U.S. on sexual activity, contraceptive usage, behavior and pregnancy intentions, pregnancies and their outcomes—the full range of reproductive health behaviors in the U.S.,” he said.

The CDC also houses a division that oversees reproductive health and, according to its website, “provides technical assistance, consultation, and training worldwide to help others identify and address male and female reproductive issues, maternal health, and infant health issues.”

While these programs exist within the agency, how they function and are prioritized can change at the discretion of presidential administrations. Gerdts pointed to the CDC’s work on abortion under the Reagan administration as an example. In the aftermath of Roe v. Wade, there was “a push towards monitoring of abortion and … a great deal of interest in tracking maternal mortality throughout the country,” including the “negative health effects of unsafe abortion in our country,” she said.

“During the Reagan administration, that work really came to a halt because the administration was anti-choice and it was not a priority.”

In 1989, a congressional committee alleged that the Reagan administration had “suppressed research on abortion because they opposed the procedure,” according to an article published that year in New Scientist. The magazine reported that David Grimes, who had worked as chief of the Abortion Surveillance Branch at the CDC, testified about the work the Republican administration had done to push its anti-choice agenda:

According to Grimes, in 1983, the White House wanted Willard Cates, then in charge of the reproductive health division of the CDC, to be fired or transferred because he appeared to back abortion. Cates was demoted and moved to the section on sexually transmitted diseases.

Grimes also told the committee that the CDC censored two articles he had written for medical journals, one because it mentioned the word abortion twice in a manuscript of approximately 5000 words. In 1985, the CDC assembled a group of experts to write guidelines to prevent transmission of AIDS from mother to fetus. ‘It was tacitly understood by everyone present that the word ‘abortion’ could not appear in a federal document during the Reagan administration,’ Grimes told the committee. The published guidelines made no mention of abortion as an option for a pregnant woman infected with HIV.

Even under pro-choice administrations that have primarily relied on evidence-based decision-making, how the president handles abortion and reproductive health can have an outsized effect on CDC policy. “I think it is particularly challenging to be a CDC employee in a country where, you know, they are charged with advancing science but there are laws on the books—I can think specifically of the Helms Amendment—that can often be misinterpreted,” said Gerdts.

Though President Barack Obama largely supported abortion access, he never clarified if the Helms Amendment, which bans foreign assistance for abortion, applied to cases of rape, incest, and life endangerment.

“While [the Helms Amendment] is really meant to prevent any funding from going to provide abortions, many of the federal agencies interpreted it as sort of a muzzle, and really shy away from even talking about scientific evidence around abortion,” said Gerdts. “So the Zika advisory and sort of guidance the CDC issued for clinicians really didn’t include pregnancy options counseling.”

Under an administration hostile to abortion and evidence-based science, things could get even worse—a major concern given the Trump administration’s embrace of anti-choice activism and disregard for science on abortion and contraception.

A science-averse CDC director could “bring back into the public eye sort of sham science,” Gerdtz said. “You can think of in the reproductive health realm …. connections between abortion and breast cancer, which have been highlighted by ‘scientists’ who are anti-choice and who review things not using rigorous methods but who are advocating for propagating these sham connections as a way of stoking fear in the public around the safety of abortion.”

Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price in a press release announcing her appointment said he believed Fitzgerald would bring her knowledge of medicine to the CDC.

“Having known Dr. Fitzgerald for many years, I know that she has a deep appreciation and understanding of medicine, public health, policy and leadership—all qualities that will prove vital as she leads the CDC in its work to protect America’s health 24/7,” he said.

Fitzgerald discussed her vision for the future of public health in an interview this year with the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. “A strong, capable, and fully functional public health system is essential for this country to have a sufficient and effective healthcare system,” she said. “Public health does those things that the private sector simply does not, and quite possibly cannot, do.”

Though Fitzgerald’s most recent position was as Georgia’s public health commissioner, she also worked as an advisor on health care to Republican Newt Gingrich and mounted two failed Congressional campaigns in the early 1990s.

A 1994 news report describing Fitzgerald’s position on abortion said she believed “the federal government should not fund abortion and opposes the freedom of choice act, but says the ultimate decision should be made by a woman in consultation with her doctor.” The Freedom of Choice Act, introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1993, said that states “may not restrict the right of a woman to choose to terminate a pregnancy” before fetal viability or “if such termination is necessary to protect the life or health of the woman.”

During her unsuccessful 1994 bid for the GOP nomination to represent Georgia’s 7th Congressional District in the U.S. House, Fitzgerald’s position on abortion rights became a contentious issue. Though Fitzgerald reportedly advocated for some abortion restrictions at the time, she did not endorse an “effort to outlaw abortions through a constitutional mandate,” leading several anti-choice groups to target her by distributing thousands of voter cards saying she was opposed to a “sanctity of life amendment,” according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

One of Fitzgerald’s opponents in the race suggested that she had performed abortions in her capacity as an OB-GYN, another article from the Journal-Constitution reported. Fitzgerald reportedly denied the claim.

Fitzgerald worked in private practice before being tapped by Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal (R) to serve in the state’s health department. While working as health commissioner, Fitzgerald launched an anti-obesity program in partnership with Coca-Cola.

As the Intercept reported, “Muhtar Kent, the chief executive and chairman of Coca-Cola Company, appeared with the governor and Fitzgerald to promote the initiative, along with a pledge of $1 million from his company to fund it. Clyde Tuggle, a Coca-Cola executive responsible for the company’s lobbying strategy, was initially appointed to the board overseeing the state anti-obesity strategy, including Fitzgerald’s SHAPE initiative.”

Unlike many other programs designed to curb obesity, “the Georgia SHAPE program notably eschewed another well-known step toward healthier living: curbing sugary beverage consumption,” the Intercept noted.

Screenshots of Fitzgerald’s biography from the Georgia health department show she identified herself as having worked in “anti-aging medicine,” according to a report from Forbes. And in screenshots from 2010, the doctor’s medical practice boasts that along with “seeing traditional gynecologic patients, we see both men and women for hormonal, nutritional, and other anti-aging concerns.”

“I’m so disappointed that the first female OB-GYN picked to head the CDC is someone who embraces the unproven and anti-scientific claims of the so-called anti-aging movement,” Cindy Pearson, executive director of the National Women’s Health Network, told Forbes.

While she didn’t comment on Fitzgerald’s appointment, Gerdts told Rewire she has a “deep respect” for those who work at the CDC. “Ensuring that they are able to do the job that they are there to do, to help the public understand what science really is and how to advance public health, is so so important,” she said.

“And reproductive health is such a crucial part of that,” she continued. “I am hopeful that any new Trump [appointment] to the CDC also adheres to the long-standing principles” of the agency.