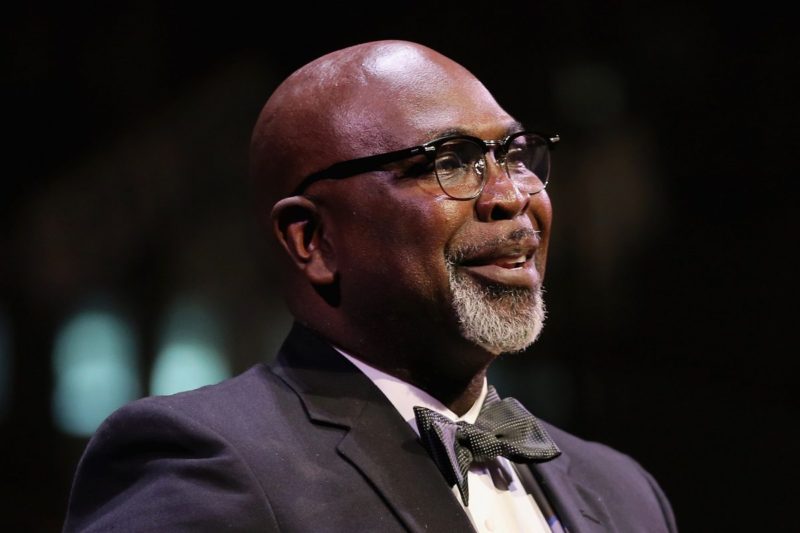

This Far by Faith: Abortion Provider Dr. Willie Parker Writes of His ‘Life’s Work’

In his memoir, Dr. Willie Parker explains that his gospel is one that views “abortion as part God” and that allows women to “find healing and understanding in church, not stigma and shame."

In recent years, individuals’ religious beliefs and access to comprehensive reproductive health care, including abortion, are increasingly at odds. Or so conservatives would say. Headlines across the United States chronicle pharmacists refusing to fill contraceptive prescriptions, Catholic hospitals declining women’s requests for surgical sterilizations at the time of cesarean sections, and even women being turned away without treatment for bleeding and cramping from dislodged intrauterine devices—all on the basis of “conscientious objection” to a variety of legal reproductive health services. Some states have even passed laws explicitly allowing health professionals to exercise their religious right to refuse service, part of far-reaching legislative efforts to chip away at abortion rights.

Obstacles to women’s access to this care are perpetrated not just by fundamentalist citizens and dogmatic legislators. While physicians are trained to embody the ideals of nonjudgment, objectivity, and evidence-based medicine, some medical staff use their religion to justify curtailing access to abortion and contraception services.

Fortunately, there are others whose faith emboldens them to serve those who cannot serve themselves. In his elegant and accessible memoir Life’s Work: A Moral Argument for Choice, to be released Tuesday, Dr. Willie Parker draws readers into his personal and professional evolution from an evangelizing Christian to his rebirth as one of the most notable, respected, and ardent champions of the U.S. reproductive justice movement. As one of the few physicians providing abortions in Mississippi and Alabama, Parker’s story is noteworthy on that merit alone. Yet what is even more enthralling is the depiction of a beautifully symbiotic existence of Parker’s love for medicine and religion, and the translation of this relationship into a moral mandate to provide compassionate abortion care.

Like many immersed in the world of abortion advocacy, Parker’s transformation was a combination of upbringing and circumstance. “The seeds of my personal revolution were in me from childhood,” writes Parker. Though he had learned “a black-and-white faith,” his journey through college, medical school, residency, and ultimately life as an OB-GYN increasingly exposed him to the very gray realities of women’s lives.

The fundamentalist notion of moral absolutes he internalized as a teenager growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, began to erode. In his own life, there was the broken condom, a potential pregnancy, and the ambitious medical student girlfriend resolute in her decision to terminate should the pregnancy take root. Another time, a young Latina teenager in California approached him for help, having been impregnated by her religious father. Finally, he was struck by how a man he calls Dr. Sweet—a “lovely,” Bible-believing chief administrator of a public hospital that served indigent Hawaiian women—halted the facility’s abortion provision because it attracted negative attention. Parker helped medical residents organize to provide abortions elsewhere and went back for more training to become an abortion provider himself.

Compelled by that incident and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s recounting of the Good Samaritan parable, Parker set forth to “exercise Christian compassion not by proxy but with [his] own, capable hands.”

And so he does. As he crafted a new professional identity as an abortion provider, Parker also began to reform his prior understanding of God into a form that would “prompt, embrace, and support [his] professional choice.” “My God,” says Parker “is a radical God who requires us to love one another because of our own sinfulness and to be generous with one another even when our impulses want to lead us back to the safety of those childish, narrow beliefs that make us afraid to act.” His gospel is one that views “abortion as part God”; that allows women to “find healing and understanding in church, not stigma and shame”; and sees a pregnancy that ends with birth as no more sacred than an abortion.

Indeed, for Parker, the sanctity of pregnancy rests not in the outcome of any particular pregnancy, whether it is the birth of a baby or the termination of a fetus. It lies in a woman’s ability to participate in the process of reproduction—by choice. It is in the procedure room “where [he is] privileged to honor [a woman’s] choice,” that Parker finds his God.

Parker’s tale of inspiration, courage, and faith comes at a time when the country is rife with divisions about race, gender, equity, and sexuality. As a profession, physicians have an obligation to challenge oppressive systems that encumber their patients and prohibit them from leading meaningful and healthful lives. Parker sees abortion not as a “terrible tragedy” committed by troubled or irresponsible women, but as a thoughtful decision by “clear-eyed individuals making a sensible choice to benefit themselves and the people around them.” He argues for the need to take back the moral high ground seized by anti-choice activists who have claimed phrases such as “pro-life” and “culture of life.”

Working through a reproductive justice lens—a theory coined by women of color in the mid-1990s as a means of elevating the needs of the most marginalized women, families, and communities—Parker travels the United States spreading a different kind of Word. He models compassionate care and mission-driven advocacy for health-care providers committed to pushing back against the recent wave of socially regressive proposals. Through his work, Parker has internalized the words of the late Holocaust survivor and peace activist Elie Wiesel, words that inspired him years ago: “Our lives no longer belong to us alone. They belong to those who need us desperately.”