‘It’s a Crisis’: Criminalizing Medication Abortion Is Already Creating Problems in Louisiana

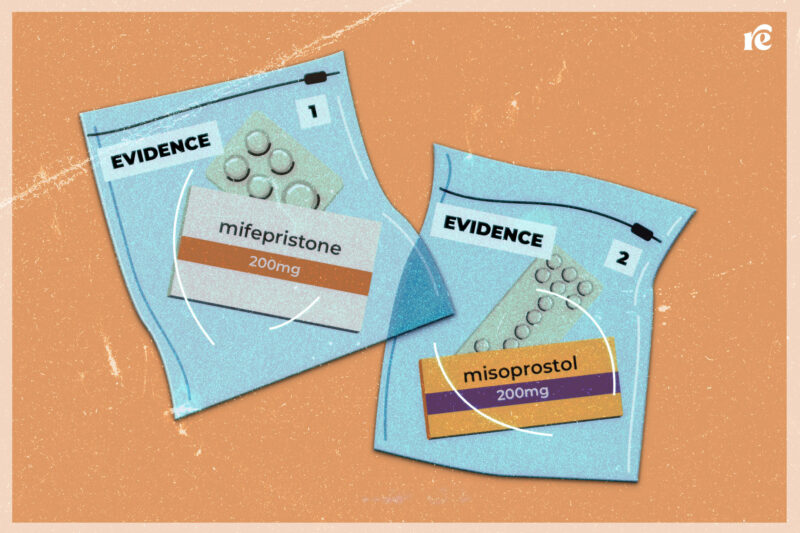

In October, Louisiana became the first state to classify mifepristone and misoprostol as "controlled, dangerous substances."

Abortion, including medication abortion, has been completely banned in Louisiana except under very limited circumstances since the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. But anti-abortion lawmakers took things one step further: On October 1, Louisiana became the first state in the country to classify mifepristone and misoprostol, the two drugs used in medication abortion, as “controlled, dangerous substances.” Possession without a prescription is a crime punishable by steep fines and up to ten years in prison.

However, both drugs are not only used for abortion care. Health-care providers use mifepristone and misoprostol to treat a variety of other reproductive and nonreproductive conditions, including for intrauterine device insertion and postpartum hemorrhage, an emergency condition where any delays in treatment are dangerous and potentially life-threatening.

Dr. Anitra Beasley, medical director at Planned Parenthood Gulf Coast—which operates in Louisiana and Texas—explained that unlike mifepristone and misoprostol, most medicines that are classified as “controlled, dangerous” substances have the potential to be abused.

“Classifying these drugs in the same category as opioids means that hospitals, health care facilities and doctors’ offices will now have to figure out new protocols for securing [them] or whether or not they can even have [these] drugs in their offices,” Beasley said. “We know these medications are safe and there is absolutely no reason to restrict their use, and any extra stipulations that you put on them will only make getting them and using them harder.”

Although it’s only been in effect for a little over two months, the new law is already causing problems for providers and patients alike.

“Even in the first few weeks what we’ve seen, particularly on the out-patient side, are delays and/or significant confusion about obtaining misoprostol for medically needed legal procedures,” said Dr. Jennifer Avegno, an emergency medicine doctor and director of the New Orleans Health Department who is overseeing an investigation into the impact of the new law.

Avegno added that this confusion has included pharmacies telling patients that they no longer carry misoprostol, or checking with their doctor to ensure that they’re not being used for an abortion even when they have a prescription showing it’s for another condition.

“On our in-patient side, I know that our physicians and in-patient pharmacists had to work really hard to develop new protocols that allow for misoprostol to be somewhat close at hand [for emergency use], but still there have been delays,” Avegno said. “And this is in a highly urbanized location that has all the resources you could have.”

But there are disparities in preparedness for the new law.

“By late September, there were providers in rural areas in the north of the state who didn’t even know this was about to happen,” Avegno said. “There is a lot of concern about what is going on in those facilities that don’t have all the resources and awareness that we do.”

But people are fighting back. The Birthmark Doula Collective, Lift Louisiana, the Lawyering Project, and several individuals filed a lawsuit on October 31 challenging the law, saying it violates the state constitution’s equal protection clause. The suit also challenges the process by which the law was passed—tacked on at the last minute as an amendment to another bill, without any public hearing, NBC News reported.

Louisiana has one of the country’s highest maternal mortality rates, and advocates and health-care providers are concerned that the new law will only worsen the situation.

“It’s a crisis, but doesn’t make us unique among states that have banned abortion,” Lift Louisiana Executive Director Michelle Erenberg said. “We have already seen the effect of Louisiana’s near-total abortion ban, and any additional laws that could restrict access to address pregnancy complications, like miscarriages and postpartum hemorrhage, are going to further exacerbate what’s already a maternal health crisis in our state.”

The law also makes a point to go after anyone who helps a pregnant person obtain the medication. Chasity Wilson, executive director of the Louisiana Abortion Fund, said misinformation affects the level of conversation they are able to have with their clients.

“Having to add in the layer of education on top of all our other work is such an unfortunate part of our jobs and creates such a huge burden,” Wilson said. “We just wish that people who are voted in to protect us actually had our best interest.”

Beasley said that since medication abortion was already illegal in the state, there was no need for the law.

“By placing it in the same category as medication with abuse potential absolutely makes it seem dangerous when it’s not,” Beasley said. “People already have difficulty accessing health care. There are already disparities in health care, and the people that are going to be harmed the most are the people who are already harmed by the health-care system.”

Even before the law went into effect, “there were reports that misoprostol was being pulled off hemorrhage carts in hospitals, which is a big concern because it’s needed quickly in an emergency situation,” Erenberg said. Health-care providers and certified nurse midwives who used to be able to prescribe and dispense misoprostol, will now need a controlled substance license, which is tracked by law enforcement.

This could prove onerous for providers working in private practices or small, community-based hospitals or clinics.

“If they don’t have a giant team of lawyers, they may just decide not to use this medication at all rather than risk being surveilled or investigated,” Erenberg said.

Although there have yet to be reports of anyone dying as a direct result of the law, “I hope I don’t hear about a tragic consequence of someone bleeding out because of it,” Avegno said.

Advocates are also concerned about copycat legislation in other states and are already preparing toolkits and talking points for providers and organizers to fight similar legislation. Dr. Daniel Grossman, director of the University of California at San Francisco’s Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health research program, said he anticipates seeing a “range of attacks” on medication abortion, even in states with near-total bans.

“This could also have the broader chilling effect of pushing people away from either using telehealth services or ordering these medications, which are by far the safest ways to end a pregnancy,” Grossman said. “Instead, they could hear about this law and think they might get arrested if they order these pills and resort to more dangerous techniques.”