Why I Went Back to School in My 40s to Work in Reproductive Health Care

Opinion: The war on abortion care compelled me to go back to school to become a family nurse practitioner.

This story is part of our back to school issue. Check out the rest of our Campus Dispatch stories here.

I wish I could say it was one single event that inspired me to return to school in my 40s to obtain my family nurse practitioner (FNP) degree, but it wasn’t. Sure, the fall of Roe v. Wade in 2022 was crushing, particularly for a pro-abortion resident in a rural, deeply red (read: lots of MAGA flags) community. But still, I didn’t really act.

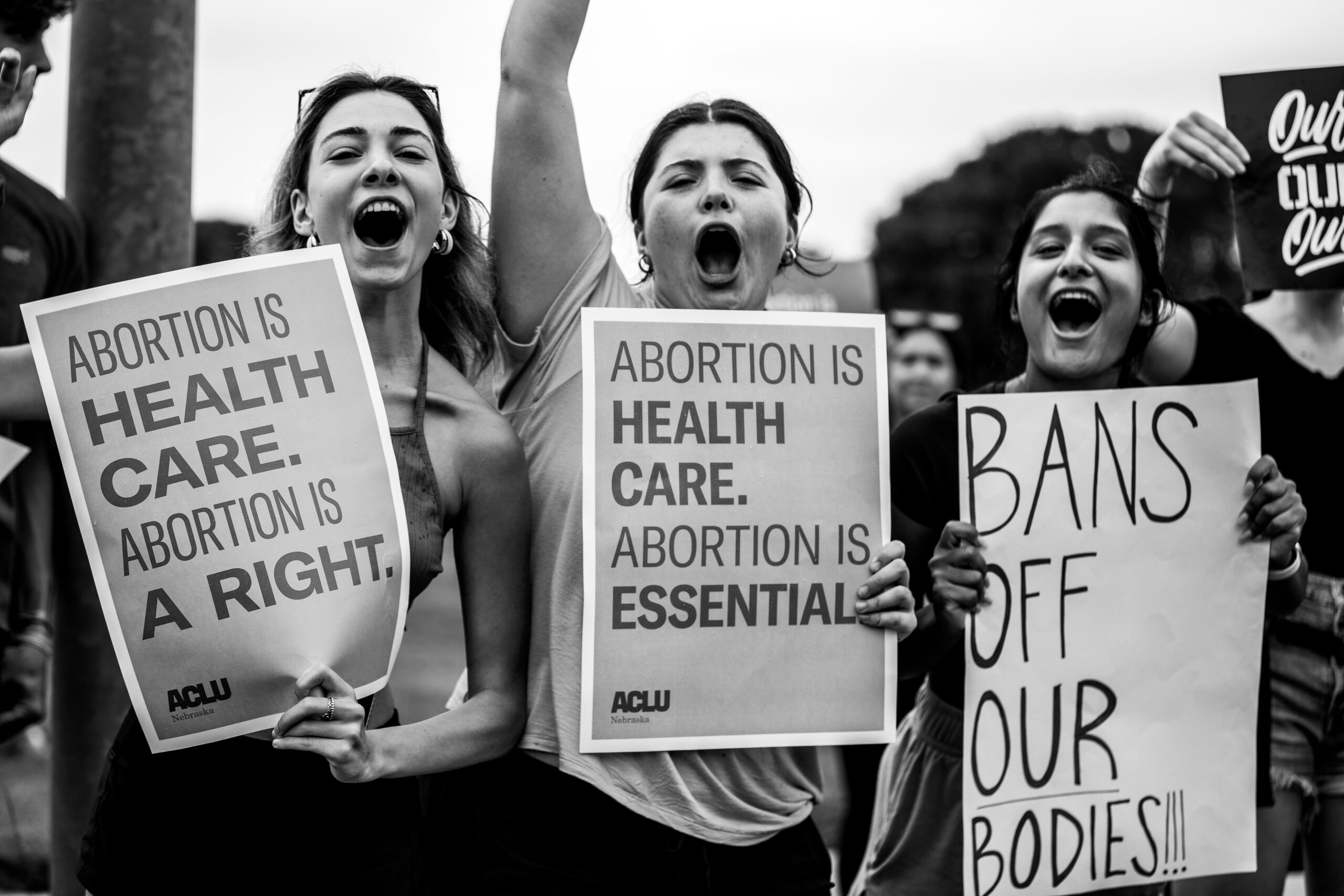

I complained. I fretted. I donated to abortion funds. I doom-scrolled. I glued construction paper to poster boards and marched in protest. I fretted some more. I went out and hate-purchased all the Plan B from several local drugstores (which have all since found a home in a domestic violence shelter in a state with a total abortion ban), but I didn’t do anything. Truthfully, like many others, I wasn’t sure what to do. All I knew was that I wanted to help people who needed abortion care.

Then came the near continuous avalanche of events—some big, some seemingly inconsequential—after the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. It seemed like each day brought a fresh new horror. “Trigger” bans, patients being told to wait and bleed in parking lots, OB-GYNs leaving their state because their practice has been targeted, and an absolute sea of vitriol aimed at Dr. Caitlin Bernard, who provided abortion care to a 10-year-old rape survivor.

It has turned into a war on reproductive health. The target: anyone seeking control over their reproductive health and future, and all the people who care about them. It’s infuriating. It’s disgusting. And it’s heartbreaking. I would be moved, but then I would always come face to face with the question, “what can I do?” and my momentum withered.

Somewhere among the dismay, that question shifted to “how can I help?” and then “how can I be most effective?” Suddenly, the answer couldn’t be more apparent. I would return to school to obtain my FNP to work in reproductive health. This is how I will fight in the war on bodily autonomy. This is my sole focus. This is how I can help. I will advocate for and provide services to people who want and need them.

It was that simple all along.

I can remember the first time I truly witnessed abortion as health care. I have been a registered nurse for 18 years, most of which have been spent in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), aka the recovery room, where patients wake up after surgery. As a PACU nurse, I remember taking care of a patient who was critically ill before her surgery: heart rate too high, blood pressure too low, breathing too fast, feverish—borderline septic shock. She was sick and needed a surgical termination of pregnancy, otherwise known as a procedural abortion.

I don’t remember all the details (nor would I share them), but the one thing I’ll never forget was the patient’s absolute relief and joy when she woke up in the recovery room. “I’m so glad it’s out,” she said. She knew she could only start healing once the cause of her strife was removed. Within the short time I had her in the recovery room, her vital signs started to stabilize, and she began to feel better. She had needed health care in the form of an abortion.

This example is sure to goad ridiculous “but her life was threatened, there are exceptions for that” comments, and I am here to say: Don’t go there. I can unequivocally say that I don’t want lawmakers determining what they deem to be “medically necessary or life-threatening.” I heard the Supreme Court arguments about whether women physically losing parts of their reproductive anatomy (fallopian tubes, ovaries, etc.) is life-threatening. In these situations, the medical providers present should determine what is “medically necessary,” and it shouldn’t have to devolve into a life-threatening situation before they are permitted to act.

Was the woman I took care of in a life-threatening situation? She was critically ill, but she was breathing on her own, and her heart was beating on its own. She wasn’t actively dying, but her condition was decompensating. What are the quantifications of “medically necessary”? Heart rate less than 30 beats per minute? Respiratory rate less than six breaths per minute? Who decides?

Here’s the thing: Medicine is a gray area. What works for one patient may not work for another. And it is nuanced. There are more factors to consider besides a patient’s outward vital signs and what (non-life-threatening) organ they may lose. Blanket statements about health care are dangerous—particularly when the statement has legislation attached.

I only retell this story because it highlights what I think abortion access should be: a decision between a patient and their health-care provider, with zero restrictions. Nationally. The health-care coverage in Missouri should be the same as that in Vermont. I want to know that I will have universal access if I visit another state. My health problems don’t change when I drive across state lines—why should my health-care options? Pregnancy is complex and can wreak havoc on even a healthy body. How can someone else dictate what the best choice is for me, my body, and my future? How dare they even try!

Most importantly, in an emergency, I want health-care providers to act in my best interest—not wait until I’m near death for fear they’ll lose their medical license. No one should be made to suffer waiting to cross some imaginary “life-threatening” threshold (if that’s even an available option) to receive medical treatment. And no one should have to parade around their trauma or disclose why they want an abortion (or contraceptives; shout out to you, potential future SCOTUS decision). I frequently tell my patients: “Your business is your business,” and that couldn’t be any truer than it is for reproductive health. I recognize these are lofty goals, but they’re the right ones. Period.

So here I am, at 43 years old, with (nearly) my first full year of FNP classes under my belt. I’ve learned how to make a Google Doc and attend Zoom sessions. I’ve brushed up on my APA skills and been introduced to Grammarly. Yes, there were hoops to jump through—applying to programs, figuring out finances, reacquainting myself with discussion posts, and the overall expectations of a graduate-level program—but it doesn’t matter. I’m getting through them. I’ve changed my work schedule to accommodate school, and I now work 12-hour shifts at a hospital every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday.

Of course, I’d like to have a free weekend again instead of writing a paper on public health, but, and I say this with my full chest: This. Is. Important. That is my motivation. None of the hoops will matter in the end. What I eventually will be doing is what matters. Ideally, I’d someday like to open a clinic. TBD. School first, grand plans second.