The Surprising History of the Appeals Court That Could Ban Medication Abortion

Once a leader in expanding civil rights, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals is now a leader in limiting government power.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article, “A surprising history of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, once a leader in expanding civil rights and now a leader in limiting government power.”

By Jonathan Entin, Professor Emeritus of Law and Adjunct Professor of Political Science, Case Western Reserve University

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has earned a reputation for strikingly conservative rulings. One of its recent decisions could put the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau out of business, another could hamstring the ability of federal agencies to enforce regulations, and a third could effectively outlaw medication abortions.

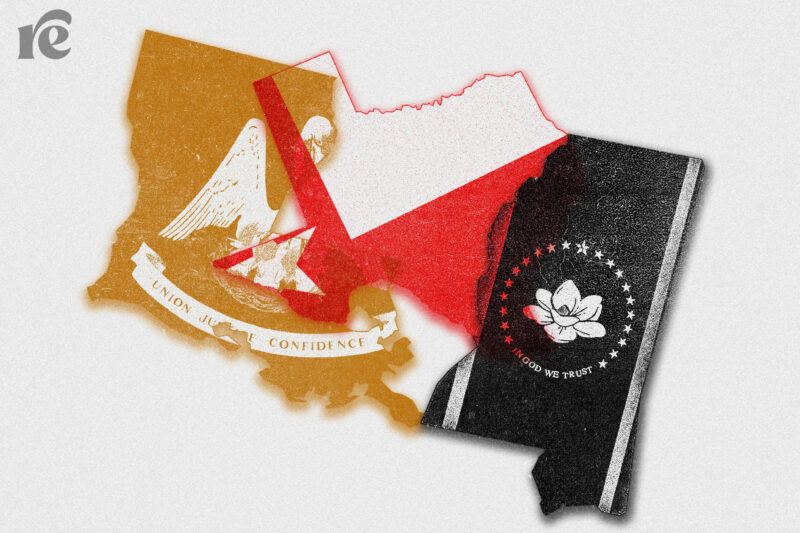

The Fifth Circuit today looks very different than it did half a century ago, when it was on the front lines of enforcing civil rights. The Fifth Circuit currently handles cases in three states: Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Until 1982, it also covered Alabama, Georgia, and Florida—the entire Deep South during the civil rights era.

Then as now, the Fifth Circuit has had a complicated relationship with a Supreme Court that was ideologically sympathetic with the lower court. At times, the Fifth Circuit was willing to go further than the Supreme Court on some issues. But the high court hesitated to rebuke the Fifth Circuit.

Understanding the Fifth Circuit’s work therefore can provide important insights into broader legal trends in the U.S.

Undercutting federal agency power

The Supreme Court can handle only a limited number of cases each year, so it tries to establish general principles that lower courts can apply.

Federal appellate courts oversee the work of federal district courts that apply those general principles. Because the devil is in the details, an appellate court can interpret those principles broadly or narrowly, and in so doing can support or undermine Supreme Court rulings on a day-to-day basis.

Several recent Fifth Circuit decisions threaten to undercut the power of federal agencies.

One notable example is the case of the abortion-inducing drug mifepristone. The Fifth Circuit in August 2023 rejected the Food and Drug Administration’s relaxation of the conditions under which that drug can be used. That decision, if upheld by the Supreme Court, could severely curtail the ability of a pregnant person to get an abortion. It could also portend widespread challenges to FDA decisions about the safety and effectiveness of drugs and medical devices.

Then, as now, the Fifth Circuit has had a symbiotic relationship with the Supreme Court. This term’s rulings will further clarify the workings of that relationship.

The Fifth Circuit suggested an alternative basis for restricting access to mifepristone. It expressed some sympathy for the plaintiffs’ broad reading of the 1873 Comstock Act, an anti-vice law, as forbidding the shipment of any “drug, medicine, article, or thing designed, adapted, or intended for producing abortion.” But that interpretation might effectively outlaw all abortions, because not only pills but virtually everything used in surgical abortions gets shipped across state lines.

Other Fifth Circuit rulings that went against the federal government are also pending before the Supreme Court this term.

Among those, one notable case could eviscerate the ability of agencies to enforce regulatory laws through traditional in-house hearings. The Fifth Circuit ruled that the Securities and Exchange Commission must use jury trials in federal court instead of those in-house hearings, that the statute giving the SEC discretion about using agency hearings was unconstitutional, and that the administrative law judges who preside at agency hearings were unlawfully appointed. That ruling, if it stands, could hamstring numerous agencies that enforce federal regulations via in-house hearings.

In a second case now before the U.S. Supreme Court, the Fifth Circuit ruled that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s funding mechanism was unconstitutional, because this agency gets its money from the Federal Reserve rather than from Congress.

That ruling could invalidate not only the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau but also the Federal Reserve itself and the entire Social Security program, including Medicare, which also do not receive their funding from Congress.

The Fifth Circuit has also expansively interpreted gun rights in cases that call many firearms regulations into question, rejecting a law that bars persons subject to domestic violence restraining orders from possessing firearms and invalidating federal regulation of ghost guns.

These rulings are part of a striking pattern of restricting federal authority that makes the Fifth Circuit distinctive among federal appeals courts across the nation.

But this isn’t the first time the Fifth Circuit has stood out.

Furthering desegregation

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, which barred racial segregation in public schools, the old Fifth Circuit compiled a courageous record in promoting civil rights.

The Fifth Circuit judges wrote or upheld rulings that required the desegregation of public schools, universities and other public facilities throughout the Deep South.

Those judges invalidated the segregation ordinance that was a key target of the 1955-1956 Montgomery bus boycott, which propelled Martin Luther King Jr. to prominence and helped to galvanize the civil rights movement. The Fifth Circuit even held the governor and lieutenant governor of Mississippi in contempt of court for defying desegregation orders in 1962.

The current Fifth Circuit, in short, looks very different from its predecessor. That is no small irony, as the Fifth Circuit sits in a courthouse named for John Minor Wisdom, one of the heroic judges of the civil rights era.

Limiting federal power

But it’s not only the Fifth Circuit that has changed. So has the Supreme Court, which is now dominated by conservative justices.

The Supreme Court that decided Brown v. Board of Education wanted public schools desegregated, but the justices left implementation to federal district judges, whose knowledge of local circumstances could make the process go more smoothly. That approach too often encouraged foot-dragging and massive resistance. Still, the Fifth Circuit’s persistence furthered the Supreme Court’s ultimate goal of breaking down segregation.

Today’s Supreme Court has very different priorities. Now, the justices are more interested in limiting federal power than in promoting civil rights.

The current court has undermined the Voting Rights Act, largely eliminated affirmative action and repudiated abortion rights.

Through its “major questions” doctrine, which requires clear congressional authorization for agencies to address problems that have a significant economic impact, the court has made it harder for agencies to undertake new initiatives.

The Fifth Circuit these days is still promoting larger Supreme Court goals. Sometimes the Fifth Circuit has gotten ahead of the justices, which might explain why the Supreme Court has reversed or limited some of the appellate court’s decisions and might do so again this year.

Then, as now, the Fifth Circuit has had a symbiotic relationship with the Supreme Court. This term’s rulings will further clarify the workings of that relationship.![]()