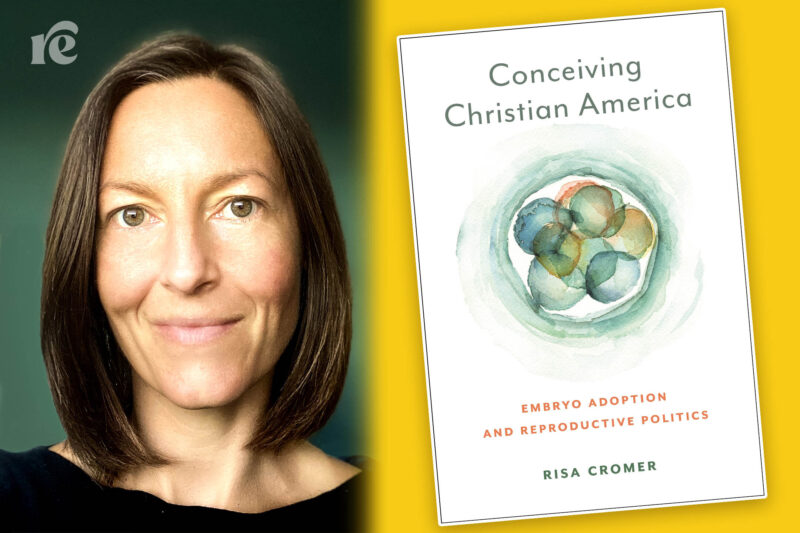

With ‘Roe’ Gone, ‘Embryo Adoption’ Could Renew Threats to IVF

White evangelicals developed "embryo adoption" in their quest of "saving" embryos and expanding the influence of conservative Christian values and power.

A few weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization to overturn half a century of federally protected rights to abortion, I received an e-newsletter from Nightlight Christian Adoptions agency. The agency’s president penned a statement responding to the ruling. “As survivors of the abortion holocaust,” it began, “a reversal of Roe is the answer to a prayer we have prayed our entire lives in which we have seen one third of our generation perish.” Emboldened by the landmark victory, he used rhetoric common among pro-life activists to praise the overturning of Roe v. Wade. This was a markedly different tone for a newsletter that did not typically discuss abortion, but rather promoted “life” through the practice of embryo adoption.

As it happened, 2022 marked a quarter of a century since the agency started the Snowflakes Embryo Adoption program—the world’s first of its kind. “Celebrate Snowflakes!” the same newsletter exclaimed. “25 years of frozen embryos brought to life!” It featured the story of a white donor couple, pictured holding their two children, promoting embryo adoption as a “blessing.” It also listed the names and photos of 16 babies recently born—tallied as a measure of the program’s “celebration of life.” In step with the newsletter’s usual tenor, the agency president praised its “strong pro-life position” for having “pioneered the field of embryo adoption” and “advocated for the personhood of embryos.” The coinciding stories in Nightlight’s newsletter make clear that opposing abortion rights and celebrating the birth of once-frozen embryos have become aligned efforts.

The newsletter landed in my inbox because I had been ethnographically investigating the practice of embryo adoption for the past 15 years. Embryo adoption is a family-making process developed by white evangelicals that facilitates the donation of frozen embryos unused after in vitro fertilization (IVF). Promoted by eight programs in the United States, this practice relies on recipients who are willing to parent any children born from procedures that transfer thawed embryos into their uteruses. Embryo adoption shares many features with what is more commonly known as embryo donation—a form of assisted reproduction also involving the legal transfer of embryos, classified as personal property, between fertility patients for procreative use—but embryo adoption differs in consequential ways. It wields pro-life rhetoric and the requirements common in Christian adoption to fulfill its expressed mission of “saving” embryos.

Yet, a closer look inside the world of embryo adoption reveals how this novel form of family-making advances the ambitions of the U.S. Christian Right far beyond abortion rights and promotions of “life.”

Understanding the political prayers of embryo adoption proponents, some of which were “answered” by the Dobbs decision, requires returning to one of the earliest moments when the practice of embryo adoption garnered national attention.

I first encountered embryo adoption through media coverage in 2005, when then-President George W. Bush put families forged through the practice on the national stage. On May 24, 2005, the president held a press conference featuring 21 children born through the Snowflakes Embryo Adoption program. During Bush’s presidency, he repeatedly gave embryo adoption—its rhetoric, its advocates, and its goals—the national spotlight.

On that day in 2005, Bush brought Snowflakes families to Washington, D.C. to dramatize his opposition to an embryonic stem cell funding bill that was gaining bipartisan support in Congress. The congressional bill arose out of mounting national enthusiasm for a pathbreaking technology that had captured the world’s attention in 1998. That year, biologist Dr. James Thomson at the University of Wisconsin led a team in establishing the first human embryonic stem cell (hESC) lines made from donated IVF embryos. This historic feat was funded by a private biotech company because of a decades-long ban on U.S. federal funding for research involving the destruction of human embryos. Reports circulated quickly about hESCs’ tremendous potential to “save lives” by treating debilitating conditions like cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, and spinal cord injuries. Harold Varmus, then-director of the National Institutes of Health, told the U.S. Senate, “This research has the potential to revolutionize the practice of medicine.” Science magazine declared stem cells the “breakthrough of the year.” Scientists lobbied the U.S. government to lift the ban so that the nascent technology could realize its promises, while critics decried research on human embryos using taxpayer dollars. Thomson’s announcement arrived as the presidential election was ramping up, thrusting frozen embryos into the middle of high-profile politics.

Histories of this moment describe it as the “embryo wars.” In 1999, President Bill Clinton became the first president to officially earmark federal monies for research involving IVF embryos. When announcing new funding guidelines for hESC research with cell lines already created, Clinton commented on its “potentially staggering benefits”: “We cannot walk away from the potential to save lives and improve lives.” From the campaign trail, the next administration promised to chart a radically different course. Soon after taking office in 2001, President George W. Bush halted federal review of hESC grant applications and rescinded the funding guidelines. In his first presidential address in August of that year, he described hESC research as “one of the most profound [issues] of our time.” He expressed a commitment to saving lives, though believed it important to balance the lives of sick children and disabled adults with frozen embryos. He then announced an executive policy restricting federal funding—though not state or private funds—to a narrow set of a few dozen existing stem cell lines “where the life-and-death decision has already been made.” He argued that this approach would not “sanction or encourage further destruction of human embryos,” which is necessary because each embryo, “like a snowflake … is unique, with the unique genetic potential of an individual human being.”

On the morning of the anticipated House vote on legislation undermining Bush’s position, he doubled down. The press conference was held in the East Room of the White House, where media, supportive legislators, and upward of 80 embryo adoption advocates and their children—who mobilized to be present within two weeks’ notice—gathered in the audience. Behind the podium during Bush’s remarks stood six white evangelical parents—four mothers and two fathers—holding their five white children. Other Snowflakes families and staff, including Ron Stoddart, the Christian lawyer who forged the first embryo adoption agreement, and Lori Maze, the program director, looked on from their seats. Children on stage sucked their thumbs, held fast to stuffed animals, clapped happily along during audience ovations, and fidgeted quietly near their parents’ legs. Some in the audience wore T-shirts stating, “This embryo was not discarded” or donned “Former Embryo” stickers.

Intermittent sounds of children cooing and crying were audible throughout the president’s remarks. “I just met with 21 remarkable families,” Bush began, referring to a meet-and-greet held in the State Dining Room just prior to the press conference. “Each of them has answered the call to ensure that our society’s most vulnerable members are protected and defended at every stage of life.” He acknowledged the “grave moral issues at stake” in the “complex debate over embryonic stem cell research,” and framed his executive policy (which the congressional funding bill sought to override) as “advance[ing] stem cell research in a responsible way.” He commended Snowflakes donors and recipients for choosing a “life-affirming” alternative to discarding or donating their embryos for scientific research, and explained the significance of his guests for the nation: “The children here today are reminders that every human life is a precious gift of matchless value … [and] that there is no such thing as a spare embryo.” In closing, he invited all attendees next door for cake to celebrate the birthdays of two “snowflake” children present that day. A year later, when officializing his first presidential veto of the congressionally approved funding bill for human embryonic stem cell research, Bush again invited Snowflakes families into the national spotlight to stand symbolically behind him and his historic pen stroke.

I missed these press conferences when they aired live on national television. At the time, I was a novice community organizer for reproductive rights paying close attention to what was then called the Bush administration’s “war on women.” Part of my job involved talking with residents in politically conservative counties in the Pacific Northwest about the spate of local and federal activities hindering access to contraception and abortion. Of the issues I discussed with people, ranging from Supreme Court nominees to legislation conferring unprecedented status to fetuses, the so-called embryo wars—and embryo adoption specifically—were not among them. Admittedly, they seemed rather distant from the frontal assaults on reproductive rights that would earn Bush recognition as the nation’s “most pro-life president.”

Not long after these press conferences aired, I left field directing for field research through graduate training in cultural anthropology. My goal was to expand my professional skill set for advancing reproductive rights and justice, which remain deep commitments of mine. Learning how to think anthropologically has powerfully transformed my understanding of reproductive politics by revealing them to be far more complex than often construed in politics and media. From the outset anthropological scholarship encouraged me to interrogate simple narratives, such as the typical representations of abortion in U.S. politics that cast multidimensional figures and issues in black and white terms. In doing so, anthropology nurtured my curiosities about the spectrum of people’s lived experiences beyond binary narratives.

Feminist anthropology, in particular, modeled how to approach reproduction as political, which means not merely as a biological process, but as a material and metaphoric site constitutive of broad political processes through which we can trace how systems of power work and persist. This framework came through clearly for me in feminist analyses of abortion politics in the 1980s, when debates were framed through rhetoric about the status of fetal life. In talking to pro-life and pro-choice activists, feminist social scientists found that their underlying concerns were actually about changing gender roles in the context of neoliberalism and the shifting place of motherhood in society. Importantly, they showed how the politicization of abortion transformed it into a strategic symbol for a range of political beliefs, through which abortion became far more than a medical procedure.

Uncoincidentally, I first noticed the figure of the frozen IVF embryo in the scholarship of a feminist anthropologist—Marilyn Strathern—who took an interest in U.S. divorce court proceedings that struggled to classify embryos as persons or personal property. Becoming curious about how embryos ended up in legal limbo, I delved deeper into the case law, where I encountered expert opinions from bioethicists, theologians, and fertility clinicians. I also read about the historical circumstances that led to the booming U.S. fertility industry that flourished within a deregulatory environment known globally as the “Wild West” of assisted reproduction. Courts were burdened with classifying in vitro embryos through case law without legal guidance because the government’s distinctively deregulatory approach to IVF meant that state and federal regulations were largely nonexistent. I took all of this in with acute awareness that state-based anti-abortion lawmakers were successfully passing hundreds of bills granting personhood status to in utero fetuses. In such a social, legal, and political context, I wondered what the fates of frozen embryos might mean for reproductive rights and justice, especially as IVF embryos became embroiled in national dramas, as they did at the turn of the 21st century.