Talking About Terrible Men: ‘Home Is Not an Innately Safe Place for a Lot of People’

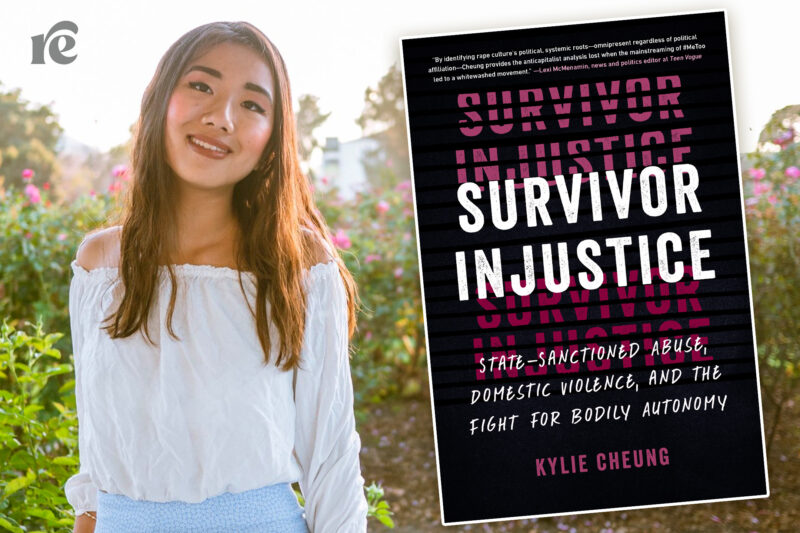

Kylie Cheung's book Survivor Injustice digs into the connections between state violence, domestic violence, and democracy.

A portion of this piece first appeared in our weekly newsletter, The Fallout. Sign up for it here.

Brett Kavanaugh. Harvey Weinstein. Johnny Depp. Jonah Hill. It seems like we are in a never-ending, slow-drip news cycle around terrible men and attempts to hold them accountable and find some kind of justice through it all.

But what does justice for survivors really entail? That’s the question at the center of journalist and Jezebel staff writer Kylie Cheung’s latest book Survivor Injustice, out on Tuesday.

I had the opportunity to read the book prior to publication and talk to Cheung about its creation, themes, and relevance when a twice-impeached insurrectionist and serial abuser is a few short steps from becoming the Republican nominee for president again. It’s hard to think of a more relevant book at a more relevant time than Survivor Injustice.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Rewire News Group: One of the things that I thought was really fantastic about the book is that it starts out connecting the dots between state violence, domestic violence, and democracy. And it’s coming out at a time when Donald Trump remains very much the frontrunner in Republican electoral politics. So, like, auspicious isn’t really quite the right word at all, but just say a word about that timing.

Kylie Cheung: In 2020, I worked on it really at the height of a lot of the really powerful criticisms of the carceral system and policing, and I think that what was so important was understanding how these systems really enact both white supremacists and patriarchal violence and how a lot of the violence that is perpetrated by the carceral system has particular impacts on survivors.

And so that was really important. And also, the intersections of that with the policing of pregnancy and how that’s such a necessary part of these conversations around both the policing of survivors and pregnancy. Because very often we find that those intersect. [Recently] it was reported that the Nebraska teen who was sentenced to jail time for her abortion—I believe that she testified about escaping an abusive relationship through trying to end her pregnancy. So that was kind of the context in which I first started the project. And then last year in 2022, obviously there was the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

I think in terms of the timing, I just think that those were two really big moments where I thought there was a really important opportunity to connect those dots of how state violence isn’t always just the very gruesome videos of police violence that we see. It really is the policies that impact especially survivors and pregnant people. I think really understanding that is not separate from but creating the conditions for interpersonal, domestic violence and being, in many ways, one in the same.

Your book has this framing that I found really powerful: The idea that threats to democracy begin at the home. And I’m hoping you can say more of that. At Rewire News Group, we are consistently trying to connect the threats to our bodies to the threats to our ballots in the country. And I don’t think it’s a framing or a way that folks are used to or quite comfortable yet really embracing or talking about, but I hope we get them there.

KC: In 2020, I was really interested in—obviously concerned by—how with COVID and lockdowns, we were seeing a rise in domestic violence, which is normal amid natural disasters, for us to see those spikes when you’re spending more time in the home and there’s greater tension and such. But I thought that what was also just really concerning was how that was happening alongside the fact that we had this huge election, and there were so many questions around about how people are going to vote and obviously the ability to mail in ballots and the ability to vote in your home—that was very important given those conditions.

But I also think what was taken for granted, and I think that that truth coexists, with how it was taken for granted that home is not an innately safe place for a lot of people. And that a lot of privilege kind of goes into that sentiment. I think it was a Rebecca Solnit essay I’d read where she talks about her experiences or her friends’ experiences with canvassing and knocking on doors for different advocacy or electoral causes, and then a husband will answer and not let you talk to their wife or something like that. Those anecdotes are very alarming. And there’s no real data, like tangible data.

What I really wanted to underscore in my work was just how domestic violence is a form of voter suppression. For years now, a big feminist struggle has been recognizing that domestic violence and abuse isn’t just a private family matter. It has huge implications in the public space in terms of your ability to vote, your ability to be politically active in your community, your ability to shape the policy outcomes that will determine maybe whether you’ll be able to escape an abusive relationship.

Your book also traces what I’d say is the failures and limitations of the carceral state for survivors and makes a case for community-based solutions, which I really appreciated. What kinds of community-based solutions do you see as both most imperative and effective?

KC: It’s such an innately tough conversation, and you can propose all of these things and then there will always be very valid and important survivor criticisms of them, or ways that they’ll fall short.

As I try to really emphasize in the book, we can talk about all of these different ideas and these different ways to support survivors, and we can listen to all of the different criticisms and feedback and ideas from survivors. But I think what it is is just that there really are no one-size-fits-all solutions, and the prison system very much isn’t that, and it’s a very punishing system for survivors. Where we move from there is really just about centering survivors’ voices, as cliche as that might sound, and just understanding that the system as it currently is is very harmful and dehumanizing toward them.

That segues nicely into another question that I have along these lines, which is the idea that “justice” is a word that gets thrown around a lot—I’m guilty of it as well. But what would your vision of actual justice for survivors entail? Is it possible to find that at all within the current system that we have? Or should we be looking for justice extra judicially?

KC: I think that true survivor justice really is economic justice. It is kind of this dismantling of a carceral system that criminalizes and dehumanizes survivors. It’s about ensuring everyone can get the reproductive care they need and that we’re not just relying on things like rape exceptions that are often entirely unhelpful and kind of just measure someone’s trauma with a yardstick basically.

I think that for me, survivor justice is an expansive understanding of how to recreate our society to ensure that people are safe and can take care of themselves, and have agency and don’t have to rely on an abuser and can access all of that health care that they need. Whether we can find that within the system as it exists or building a new one, I really do think survivor justice really relies on us being able to imagine beyond the conditions that we live in. I also think it requires us to be creative about operating within the conditions that we do live in, in the reality that we are in. So I think it’s a bit of both.

The number of women in my cohort, so I’m almost 50, who during the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings reached out and said, “I understand myself now to be a survivor of sexual violence” because they heard themselves in Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony was many, which I think just speaks to that idea that the stories then inform whether or not we identify [as survivors] ourselves.

KC: Oh yeah. I can’t believe I haven’t even talked about everything with Kavanaugh. I think that something else I really wanted to stress in this book was just the importance of putting things to words and having these definitions and being able to speak on these experiences because sometimes people can experience sexual violence, sexual trauma and not really process or understand that that’s what it was for a very long time after. And it really just takes, in many ways, these public reckonings sometimes.