Why Pregnant People Are Choosing Birth Centers for Delivery

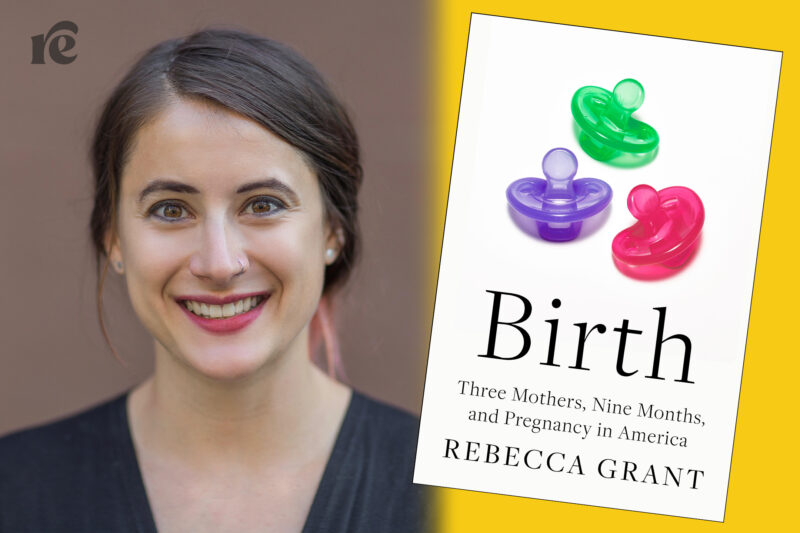

In Birth, journalist Rebecca Grant follows the journeys of three pregnant people who have all considered giving birth at a birthing center.

After months of preparing to give birth to her first child at a birthing center, T’Nika’s plans had to change: She needed a caesarean section due go her baby’s placement during delivery. As a Black woman giving birth during COVID-19, giving birth outside of a traditional hospital sounded appealing. But her baby had other plans, and due to the birthing center’s working relationship with a nearby hospital, T’Nika was quickly transferred.

T’Nika’s story is one that’s shared in the book Birth: Three Mothers, Nine Months, and Pregnancy in America, which is out today, illustrating how the number of people giving birth at birthing centers or at home has increased, especially for Black people, since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Birth, journalist Rebecca Grant writes about the journeys of three pregnant women, including T’Nika’s, all of whom have considered giving birth at a birthing center in Portland, Oregon, and the importance of pregnant people having the ability to choose the right birthing option for them.

“It’s ultimately about ensuring that people have access to the environment that is the best fit for them both in terms of the medical care that they want or need,” Grant said.

Rewire News Group chatted with Grant on her reporting on birthing centers, ethics on reporting on maternal health care in a polarized environment, the importance of an intersectional framework when looking at people’s birthing experiences, and more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Rewire News Group: Was there a moment in your own reporting and/or life that drew you to wanting to focus more on birthing centers?

Rebecca Grant: When I first started covering kind of this beat, most of my work was focused on abortion. As I was doing that reporting, I started to cover more stories about maternal health care as well. A lot of the themes that came up in the reporting that I did on abortion were also deeply relevant to conversations about maternal health care. As I was reporting on maternal health care, I was sort of introduced to the concept of midwives; not that they weren’t on my radar, but just as sort of an avenue that I might look into. That was how I found birth centers or became interested in birth centers through the portal of midwives.

In terms of the books specifically, there were a couple of reasons why birth centers appealed to me. I liked that it was sort of like a halfway between the home and the hospital. When I was first conceiving of the book, one of my ideas had been to focus on three different women or three different stories, but maybe have one be at home, one be at a birth center, and one be at a hospital, too, because I was really interested in the different experiences and histories across environments. In an effort to sort of have more cohesion, and for there to be a specific setting for the book, I thought birth centers made sense because it’s this halfway point.

RNG: Pregnancy and giving birth has become such a politicized topic. Could you talk about the importance of an active, ongoing journalistic consent process in your reporting?

RG: When I was just at the birth center, shadowing some of the midwives or just meeting people who are coming in and out, I would always have either myself or the midwife that I was spending time with introduce me and check with the client before an appointment if it was OK for me to be in the room. In almost all cases, the client said that it was fine—one or two times they said no, and I would just go wait out in the lobby. I would be really clear about sort of what I was doing and if they were going to be identified, what that process would look like.

Then with the three main characters, I had really long conversations with each of them about what would be involved in terms of the time commitment, in terms of me digging around into there, let you know, “I’m going to want to look at your medical records, I’m going to want to talk to your mom or your partner, I’m going to want to sit in on appointments, if I can,” so that there weren’t any surprises. I had told each of them that if they wanted to go by a pseudonym, that was something we could talk about—not go by their real first names—but they all chose to go by their first names. That was something I would also check in about periodically.

In terms of the content, I tried to be really clear the whole time of, “If there’s anything that you don’t want to be included, just let me know, or we’ll talk about it, that’s fine.” For the most part, they were just incredibly open in a way that I really appreciated. I think it was interesting, conversations Jillian and I would have, because consent is such a big part of midwifery practice and practicing informed consent and asking people for their permission for everything. That was kind of an interesting commonality to identify, it was that me constantly checking in and that way, it was something that she was also trained to do as a midwife.

RNG: Two out of the three women who planned to give birth at a birthing center then had complications, which led them to be transferred. Did this change your approach in writing this book?

RG: The transfer rate for first-time mothers who give birth or first-time people who give birth outside of a hospital is relatively high, so just statistically speaking, I was maybe expecting that one person might make a transfer.

I think that there was a fact that each of the moves that just speaks to that complexity, and that unpredictability in a way that I felt like was really important. Even if you are planning to go to a hospital and that’s where you end up giving birth, that doesn’t mean that everything is going to go according to plan even if you don’t move locations. A lot of people who I’ve interviewed over the years have grappled with feeling like a failure when things don’t go according to plan. So being able to portray people who things didn’t go to plan, but it ended up being OK, it ended up being what they needed. I was grateful that I was able to include that sort of complexity in there.

One of the kind of arguments that the book makes around how to improve our maternal health-care system is about the importance of smooth integration and relationships between midwives and birth centers, and out-of-hospital providers with doctors and hospitals so that transfers can happen smoothly—both medically speaking and just in terms of how people are treated. And, so, I think that the fact that everyone kind of moves locations, also just emphasize[s] that point as well.

RNG: What resources were the most helpful for you in learning and understanding the history of midwifery in the United States, including anti-Black laws making this practice more difficult to do in some states?

RG: I would say some books that I either read or reread were Killing the Black Body by Dorothy Roberts; I read a whole slew of midwife memoirs, like Listen to Me Good, which was a memoir from Margaret Charles Smith [and Linda Janet Holmes], and Motherwit by Onnie Lee Logan. That was their firsthand experiences of being African American grand midwives in the South during this period, when a lot of these laws that were trying to phase midwives out in a very targeted way were coming. You’re able to sort of understand what it was like to get this letter from the health department and find out that your license wasn’t going to be renewed.

Then, also, a lot of drawing on interviews and articles and speeches of people like Dr. Joia Adele Crear-Perry, who’s the founder of the National Birth Equity Collaborative.

RNG: Why is it important that journalists include external factors that could impact people’s lived experiences? I appreciated that throughout this book, there was an emphasis on how anti-Black racism in medicine shaped one woman being drawn to the birthing centers, as well as the fact that COVID-19 was and continues to make going to hospitals potentially dangerous for pregnant people.

RG: We’re all affected and shaped by our environment, and that has an impact on our health. I would also venture to say that it’s particularly strong when it comes to pregnancy and birth, because those aren’t just medical events. They’re also social and cultural and emotional events. They touch so many aspects of lives. Once you start digging, nothing is happening in a vacuum. Everything is interconnected. These are the sort of ideas that people like Loretta Ross and Kimberlé Crenshaw have been saying for and advocating for decades. Any kind of reproductive justice organization that applies that framework to their work is always looking at so many different factors that are at play. There’s no one answer to the question “Why are our outcomes the way that they are? Or why are the disparities as persistent?”

I think one of the things that COVID did was it changed the risk calculus for a lot of people because for a lot of people, there’s been this idea that the hospital is the safest place to be to give birth. But, in early COVID, people were worried about diseases spreading, or they’re worried about being separated from their baby, they’re worried about not being able to have a support person with them. I think that that led to a change in sort of weighing the pros and cons for some people that maybe wouldn’t have happened or would have happened on a slower timeline.